Major Thomas R. Livingston was a Confederate soldier during the Civil War and a participant in the Bleeding Kansas era that preceded the war.

Tomas Livingston was born on December 6, 1820, to Thomas and Sarah Kennedy Livingston in Montgomery County, Missouri. He grew up to marry Nancy King Gibson, and the couple would eventually have three children. He moved with his family to a site just west of Carthage, Missouri, in 1851. While digging a cellar, he discovered lead ore, and with his half-brother, William Parkinson, he erected a smelter and entered the lead mining boom in southwest Missouri. His mine soon became the wealthiest lead strike ever made in southwest Missouri. Thirty million dollars worth of lead and zinc was mined there, and the largest chunk of pure lead ever found in the district came from there.

The successful and prominent businessman Livingston also owned a general store, hotel, saloon, real estate in three counties, and actively traded livestock.

During the Bleeding Kansas era in the 1850s, Livingston became a captain of a Border Guard unit raised to defend western Missouri against the marauding Kansas Jayhawkers. At this time, Free-State Kansans were fighting with pro-slavery advocates of Missouri as to whether Kansas Territory would become a slave state or a Free-State. Kansas eventually entered the Union as a free state a few months before the Civil War began.

By that time, Livingston had become a wealthy businessman and community leader. Although he owned only one slave, he believed in defending southern states’ rights. His wealth would continue to grow during the war, as most of the Confederacy’s lead used in armaments came from Missouri mines, and thousands of pounds were shipped east.

In the summer of 1861, Livingston was elected a captain in the 11th Cavalry Regiment of the Missouri State Guard. Serving under Colonel Sanford Tablbott, Livingston participated in raids across the Kansas border, attacking several towns. He effectively controlled most of Jasper County, Missouri, during the war. Although most of his activities centered on Jasper County and crossed over into Arkansas and Indian Territory, patrolling along the Kansas-Missouri border often brought him into Vernon County, Missouri, on the western border just across from Fort Scott, Kansas.

On September 8, 1861, Livingston joined John Mathews in a 150-man cavalry raid into Kansas. In retaliation for the burning of Missouri towns, they sacked and burned the small town of Humboldt. Many Indians were with them, and Humboldt was targeted because it had become a refuge for abolitionists who had tried to settle illegally on Indian land.

Livingston and his men continued to patrol the border with Kansas and campaigned south into Arkansas and Indian Territory (Oklahoma.)

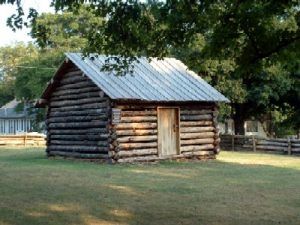

As early as the spring of 1862, Livingston established a hideout in Kansas for himself and his men. Livingston’s Hideout was probably the only permanent Confederate military camp inside Kansas during the Civil War. In the very corner of Cherokee County in southeast Kansas, it was about two miles north of the border with Indian Territory and less than 100 feet west of the border with Missouri. It was five miles west of Baxter Springs, where a series of Union military posts existed from 1862 to 1863. During the war, no Union troops knew of its existence. Located in a heavily wooded area, a road ran just west of the campsite and about 100 feet above it. However, the campsite area could not be seen from the road. A creek was about 50 feet below the campsite, and a hill was to the east, inside Missouri. The use of Livingston’s hideout proved an incredible frustration for the area’s Union troops. The troops often chased the guerrillas, only to have them scatter and seemingly vanish.

After the defeat at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in March 1862, the Missouri State Guard was disbanded, and many men were transferred to the east. When Livingston and others returned to Jasper County, they arrived to find Union militia stationed throughout Southwest Missouri and a garrisoned presence at Carthage. Under martial law, declared a year earlier, the Federal troops had the right to take what they needed from area citizens, including crops, flour, and other supplies. Believing that the Union soldiers were ignoring area citizens’ civil and constitutional rights, Livingston gathered the remainder of those who had returned from the 11th Cavalry Regiment. The soldiers then recruited more men and organized a cavalry force that became known as “Livingston’s Rangers,” which was authorized under the Partisan Ranger Act of the Confederate Congress.

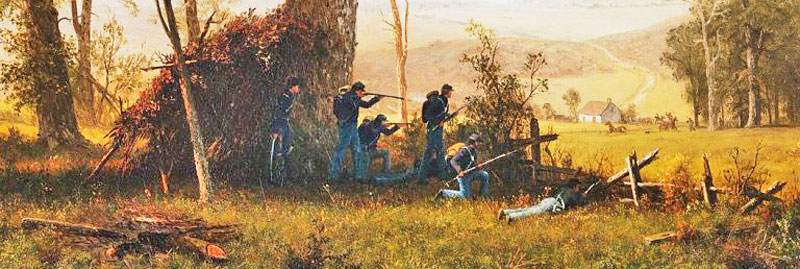

Livingston and his men were a menace in the Ozarks. They waged many crimes against local residents, refugees, and Union troops. Livingston’s men were notorious for committing acts of arson, murder, robbery, and disrupting Union supply lines. They frequently engaged Union patrols inflicting heavy casualties. Union troops were outraged by Livingston’s ruthless tactics, as he often refused to take or release prisoners. Livingston preferred murder over capture and was known to shoot unarmed or wounded soldiers at point-blank range. As a result, Livingston became a priority target of the Union forces.

Livingston enlisted his men in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States, and they were designated as the 1st Battalion Missouri Cavalry, also called the 1st Indian Brigade. The group would come to be known as the Cherokee Spikes. Though officially sanctioned under the Confederate Army, they were commonly called guerrillas, as they operated more like an independent band of outlaws. Some Confederate officers disapproved of their illicit activities, with one officer stating that some of Livingston’s men were “no better than thieves and robbers.”

On May 18, 1863, Livingston’s scouts reported 60 soldiers from Colonel James Williams’ African American regiment foraging near Sherwood, Missouri. Livingston led 67 of his “best-mounted men” to engage the federal forces. Reports indicated between 22 and 32 African American troops and 20-22 white artillerymen from the 2nd Kansas Battery were at the home of Mrs. Rader. Mrs. Rader’s husband was one of Livingston’s men, and the Federal forces were foraging for supplies in her home. Livingston surprised the Federal troops and killed many, reporting enemy losses at “negroes, 23, and 7 white men.” He also captured three white soldiers and two African American soldiers.

The following day Union troops from Fort Blair, Kansas, in Baxter Springs, assaulted and burned the town of Sherwood and 11 surrounding farmhouses. Most of Livingston’s men lived in and around the area. The citizens fled to Texas, and Sherwood was never rebuilt.

On May 20, Colonel Williams and Livingston entered negotiations for a prisoner exchange. Livingston offered to exchange the three white soldiers for any Confederate men Williams might be holding. “As for the Negros,” Livingston said, “I cannot recognize them as soldiers; in consequence, I will have to hold them as contrabands of war.” Colonel Williams accepted the exchange for the white prisoners but warned Livingston of the maltreatment of the African American men.

In regard to the colored men, prisoners, belonging to my Regiment, I have this to say that it rests with you to treat them as prisoners of war or not, but be assured that I shall keep a like number of your men as prisoners until these colored men are accounted for. You can safely trust that I shall visit a retributive justice upon them for any injury done them at the hands of the Confederate forces. If twenty days are allowed to pass without hearing of their exchange I shall conclude that they have been murdered by your Soldiers or shared a worse fate by being sent in chains to the slave pens of the South, and they will be presumed to be dead.

— James Williams Letter to Thomas R. Livingston, May 21, 1863

The white prisoners were exchanged on May 22, but the banter between Williams and Livingston escalated the threat of violence. One of the African American prisoners was killed in Livingston’s camp. Williams demanded the man who committed the murder and threatened, “If you fail to comply with the demand, and do not within 48 hours, deliver to me this assassin, I shall hang one of the men who are now prisoners in my camp.” Livingston reported the murder as an outsider who had entered his camp, and his men were not responsible. Livingston added, “I am not aware that you have any [men] belonging to my command consequently, the innocent will have to suffer for the guilty.” At this point, negotiations completely deteriorated and ended with both parties killing prisoners.

However, Livingston failed when he ventured outside his home territory. On July 11th, 1863, he led his Rangers northeast to Stockton, Missouri, hoping to capture supplies from the small Union garrison headquartered in the Cedar County courthouse. The former and future sheriff, Vernon County’s Captain William Henry Taylor, accompanied him. When 250 attackers managed to surprise the town preoccupied with political speeches, about 20 Union militiamen holed up in the courthouse.

Livingston then rode at the front of his men, waving a short-barreled carbine urging them toward the fight. Most of the guerillas dismounted and began firing at the courthouse from all sides. As the Union men tried to shut the doors and barricade themselves inside, the leader charged the courthouse, yelling to his men. By this time, the militiamen had become aware of his identity, and Livington was shot, knocking him out of his saddle. Three others, including Vernon County’s Bud Elder, fell nearby.

Shocked and overwhelmed that their leader was killed, the rest of the Rangers began a confused retreat. When the militiamen emerged from the courthouse and approached the bodies, Livingston grabbed his carbine and tried to regain his feet. He was stopped by six shots fired into his body. Livingston had been wearing a steel breastplate and thus survived the first shot.

Livingston and three other Rangers were buried in an unmarked mass grave, along with other Civil War dead, in the southwest quadrant of the Stockton City Cemetery. In that area is a marker that reads: “To mark the final resting place of those persons unknown.”

“It was the hardest blow the guerrillas of that section have received during the war.” — Union Soldier

Afterward, Livingston’s battalion split up. Three months after this fight, General Jo Shelby and his men burned the Cedar County courthouse in retaliation.

When the Civil War was over, Livingston’s victims flocked to Jasper County to file their claims of restitution for his actions against his estate. Before it was over, his extensive property was confiscated and dissipated, paying off scores of lawsuits against him for his wartime deeds.

More than a century later, Livingston’s Hideout was finally discovered. In the 1980s, the site was found and explored by the Baxter Springs Historical Society during the construction of a new home.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, October 2022.

Also See:

Sources:

Adventures of Billy Max

Civil War Virtual Museum

Find a Grave

Nevada Daily Mail

Ozarks Civil War

Wikipedia