New Netherland was a 17th-century Dutch Republic colony on North America’s northeast coast. The Dutch claimed and settled areas now part of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Connecticut, with small outposts in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

In 1609, two years after English settlers established the colony of Jamestown, Virginia, the Dutch East India Company hired English sea captain and explorer Henry Hudson to find a northeast passage to India. After unsuccessfully searching for a route above Norway, Hudson turned his ship west. He sailed across the Atlantic, hoping to discover a “northwest passage” that would allow a ship to cross the North American continent, gain access to the Pacific Ocean, and, from there, India.

After arriving off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, Hudson explored the region now occupied by New York City. He then sailed up the Hudson River, later named for him, as far as present-day Albany, New York, before the river became too shallow for his ship to continue north. He then returned to Europe and claimed the entire Hudson River Valley for his Dutch employers.

The Dutch issued patents in 1614 for developing New Netherland as a private, commercial venture. Soon after, Dutch entrepreneurs established New Netherlands to capitalize on the North American fur trade. The Dutch depended on the indigenous population to capture, skin, and deliver pelts to them, especially beaver. Their first partners were the Algonquian, who lived in the area. They built Fort Nassau at present-day Albany, New York, among the Mahican tribe in 1614. The fort was established to defend river traffic against interlopers and to conduct fur trading operations with the natives. However, its location proved impractical due to repeated flooding, and it was abandoned in 1618.

After unsuccessful efforts at colonization, the Dutch Parliament chartered the West India Company to organize and oversee all Dutch ventures in America. Thirty families arrived in 1624, establishing a settlement in present-day Manhattan. Much like English colonists in Virginia and the French to the north, the Dutch settlers did not take much interest in agriculture and focused on the more lucrative fur trade. The new immigrants traded with the Algonquian Lenape tribe around New York Bay and along the Lower Hudson River. Collectively, they called the Algonquian tribes the River Indians.

In 1626, Director General Peter Minuit arrived in Manhattan, charged by the West India Company with administering the struggling colony. Minuit “purchased” Manhattan Island from the Native Americans, formally established New Amsterdam, and consolidated and strengthened a fort far up the Hudson River at present-day Albany named Fort Orange. The colony grew slowly as settlers, responding to generous land grants and trade policies, spread north up the Hudson River.

However, the slow expansion of New Netherland caused conflicts with both English colonists and Native Americans in the region. In 1628, the Mohawk, who were members of the powerful Iroquois Confederacy, conquered the Mahican tribe, who retreated to Connecticut. The Mohawk soon gained a near-monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch, as they controlled the upstate Adirondacks and Mohawk Valley through the center of New York.

In the 1630s, the new Director-General, Wouter van Twiller, sent an expedition from New Amsterdam to the Connecticut River into lands claimed by English settlers. Faced with the prospect of armed conflict, Twiller was forced to back down and recall the expedition, losing any claims to the Connecticut Valley. In the upper reaches of the Hudson Valley around Fort Orange, where the needs of the profitable fur trade required a careful policy of appeasement with the Iroquois Confederacy, the Dutch authorities maintained peace. Still, corruption and lax trading policies plagued the area. In the lower Hudson Valley, where more colonists were settling on small farms, Native Americans came to be viewed as obstacles to European settlement. In the 1630s and early 1640s, the Dutch Director-Generals carried on a brutal series of campaigns against the area’s Native peoples, mainly succeeding in crushing the strength of the “River Indians” but also managing to create a bitter atmosphere of tension and suspicion between European settlers and Native Americans.

The year 1640 marked a turning point for the colony. The West India Company gave up its trade monopoly, enabling other businessmen to invest in New Netherland. Profits flowed to Amsterdam, encouraging new economic activity in producing food, timber, tobacco, and, eventually, slaves. In 1647, the most successful of the Dutch Director-Generals arrived in New Amsterdam. Peter Stuyvesant found New Netherland in disarray. The previous Director-General’s preoccupation with the Native Americans and border conflicts with the English in Connecticut had significantly weakened other portions of colonial society. Stuyvesant became a whirlwind of activity, issuing edicts, regulating taverns, clamping down on smuggling, and attempting to wield the authority of his office upon a population accustomed to a long line of largely ineffective Director-Generals.

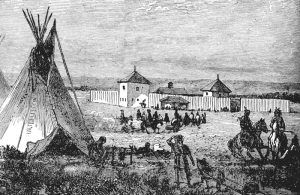

Eventually, Stuyvesant cast eyes upon the small settlements developed along the Hudson River Valley between Fort Orange and New Amsterdam. In 1652, 60-70 settlers had moved down from Fort Orange to an area where the Rondout Creek met the Hudson River, the site of present-day Kingston. The settlers farmed the fertile floodplains of the Esopus Creek side-by-side with the Esopus Indians, the area’s original settlers. Inevitably, land disputes brought the two sides to the brink of war, with the Europeans and the Esopus Indians engaging in petty vandalism and kidnapping.

In 1657, seeing the strategic practicality of a fort halfway between New Amsterdam and Fort Orange, Director General Stuyvesant sent soldiers up from New Amsterdam to crush the Esopus Indians and help build a stockade with 40 houses for the settlers. Board by board, the settlers took their barns and houses down and carted them uphill to a promontory bluff overlooking the Esopus Creek floodplain. They reconstructed their homes behind a 14-foot high wall made of tree trunks pounded into the ground, creating a perimeter of about 1200 x 1300 feet. By day, the men left their walled village, which Director-General Stuyvesant had named “Wiltwyck,” to go out and farm their fields, leaving the women and children primarily confined within the stockade. The villagers lived this way until 1664, when a peace treaty ended the conflict with the Esopus Indians.

Stockade Historic District, Kingston, New York, courtesy Friends of Historic Kingston

Though no longer needed, the stockade was left standing well into the late 17th century, and wooden remnants of the wall were rediscovered on Clinton Avenue during an archaeological dig in 1971. However, the streets of the original village remain laid out just as they were in 1658. Although the wooden houses of the original settlers are long gone, the second generation of homes still survives. These stone houses are fine examples of 17th-century Dutch stone buildings, and 21 still stand within the original layout of the stockade, listed in the National Register of Historic Places as contributing members of the Stockade Historic District. Many of these homes began as single rooms with a loft above and gradually expanded. However, the simple limestone and mortar materials hauled directly from the fields outside the stockade are still quite visible. Direct links to the age of Dutch colonization, the sturdy construction of these houses has served generations of Kingston residents and are still in use today.

Although Wiltwyck, the second large settlement established north of New Amsterdam, grew quickly, the successes of the Stuyvesant administration put New Netherland in danger. The colony was proving quite profitable, as New Amsterdam had developed into a port town of 1500 citizens, and the incredibly diverse population (only 50 percent were actually Dutch colonists) of the colony had grown from 2,000 in 1655 to almost 9,000 in 1664. “Problems” with Native Americans were mostly over, and stable families slowly replaced single adventurers interested only in quick profits. New Netherland produced immense wealth for the Dutch, and other foreign nations began to envy the Hudson River Valley’s riches.

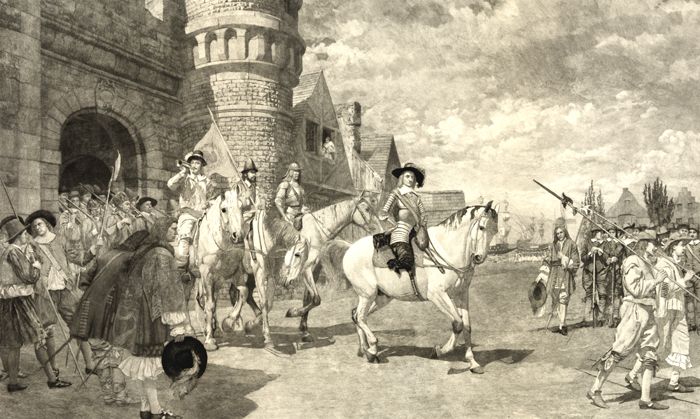

During the Second Anglo-Dutch War in 1664, King Charles of England granted his brother, James, Duke of York, vast American territories, including New Netherland. James immediately raised a small fleet and sent it to New Amsterdam. Director General Stuyvesant, without a fleet or any real army to defend the colony, was forced to surrender the colony to the English war fleet without a struggle. In September 1664, New York was born, effectively ending the Netherlands’ direct involvement in North America. However, in places like Kingston, the influences of Dutch architecture, planning, and folklife can still be seen.

The inhabitants of New Netherland were European colonists, American Indians, and Africans imported as slave laborers. The colony had an estimated population between 7,000 and 8,000 at the time of transfer to England in 1664, half of whom were not of Dutch descent.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Henry Hudson – Northeast Explorer

New Amsterdam – The Beginnings of New York City

Sources: