“I was born with the devil in me. I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than the poet can help the inspiration to sing — I was born with the ‘Evil One’ standing as my sponsor beside the bed where I was ushered into the world, and he has been with me since.”

— H.H. Holmes

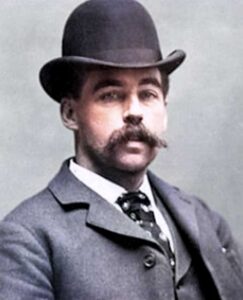

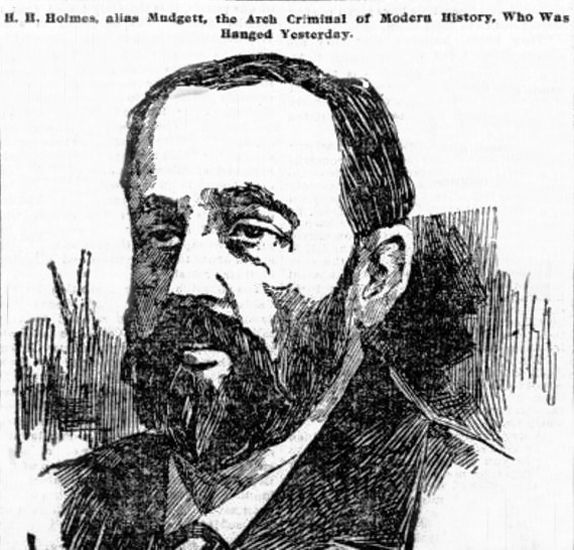

Herman Webster Mudgett, better known as Dr. Henry Howard Holmes or, more commonly, H. H. Holmes, was a prolific serial killer who operated in the late 19th century.

Said to have killed as many as 200 people, he would eventually confess to 28 murders, but only nine could be confirmed. If his murderous activities weren’t enough, he was also a con artist, a bigamist, and the subject of more than 50 lawsuits in Chicago alone.

Mudgett was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire, on May 16, 1861, to Levi Horton Mudgett and Theodate Page Price, both of whom were descended from the early English settlers. One of five children, his father was a farmer who sometimes worked as a trader and house painter. His parents were devout church-goers. Young Herman was said to have shown high intelligence at an early age and excelled at school. However, his peers bullied him, and there were signs of what was to come – practicing surgery on animals and cruelty towards smaller children. Some accounts indicate that he may have been responsible for the death of a friend.

Clara Lovering Mudgett

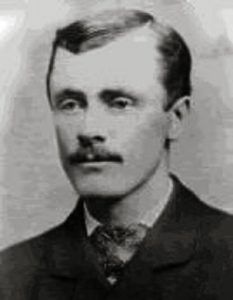

At the age of 16, Holmes graduated from high school and took a teaching job in Gilmanton and later in nearby Alton. On July 4, 1878, he married Clara Lovering, the daughter of a well-to-do family, who would help to pay for his education. The couple would have a son in 1880.

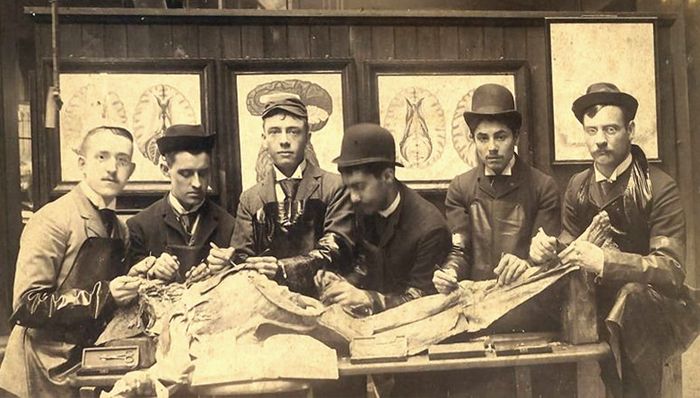

In 1879, at the age of 18, he enrolled in the University of Vermont in Burlington but left after only one year. Two years later, in 1882, he entered the University of Michigan’s Department of Medicine and Surgery and graduated in June 1884. He worked in the anatomy lab under the chief anatomy instructor during his schooling. At some point, he also apprenticed under Dr. Nahum Wight, a noted advocate of human dissection in New Hampshire. It was there that he discovered a passion for dissecting cadavers.

During this time, Mudgett began a life of various frauds and scams. As a medical student, he stole corpses, burned or disfigured them, and then planted the bodies, making it look like they had been killed in an accident. In the meantime, he took out insurance policies on them and collected the money once the bodies were discovered. He was also known to have profited by stealing and selling cadavers and skeletons. Known to have developed a “passion” for dissecting corpses, he was thought to have used the bodies for experiments, as well.

At the same time, housemates described Mudgett as treating Clara violently, and in 1884, before his graduation, she and their son moved back to New Hampshire, and she never saw him again.

He then moved to Mooers Forks, New York, where a rumor spread that Mudgett had been seen with a little boy who later disappeared. Herman claimed the boy went back to his home in Massachusetts. No investigation took place, and Mudgett quickly left town.

He was next living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he got a job as a keeper at Norristown State Hospital, but he quit after a few days. He then went to work in a drugstore in Philadelphia, but while he was working there, a boy died after taking medicine that was purchased at the store. Holmes denied any involvement in the child’s death and immediately left the city.

In 1886, though he wasn’t divorced from Clara, Mudgett married a woman named Myrta Belknap in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the couple eventually had a daughter. He filed for divorce from Clara a few weeks after marrying Myrta, alleging infidelity on her part, but the claims could not be proven, and the suit went nowhere. Surviving paperwork indicated that she probably was never even informed of the suit, and the divorce was never finalized.

Also, in 1886, Mudgett changed his name to Henry Howard Holmes, probably to hide from the insurance scams that would later be discovered. He and his wife Myrta then moved to Illinois, where they lived in Wilmette. However, Holmes spent most of his time in Chicago.

There, he went to work at Holton’s drugstore at the southwest corner of South Wallace Avenue and West 63rd Street in Englewood. Dr. Edward Holton was a fellow Michigan alumnus, only a few years older than Holmes. Holmes proved himself to be a hardworking employee and eventually bought the store.

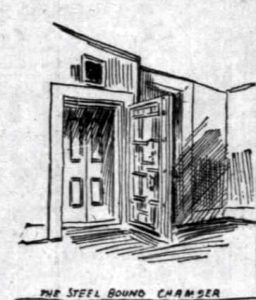

He then purchased an empty lot across from the drugstore, where construction began in 1887 for a two-story mixed-use building, with apartments on the second floor and retail spaces, including a new drugstore, on the first. When Holmes declined to pay the contractors, they sued in 1888. However, construction continued, during which time, Holmes hired and fired several construction crews for two reasons – 1) so that no one would have a clear idea of what he was doing and 2) so he could claim bad workmanship and refuse to pay for services. Later, the police would determine that he never paid a cent for any of the materials that went into the building.

Holmes Building

The neighborhood folks soon dubbed the building the “Castle.”

After construction in 1891, Holmes placed ads in newspapers offering jobs for young women and advertised the Castle as a lodging place. He also placed ads presenting himself as a wealthy man looking for a wife. All of Holmes’ employees, some hotel guests, fiances, and wives were required to have life insurance policies, with Holmes or one of his aliases being the beneficiary. People started to disappear.

By this time, Holmes was not being faithful to his second “wife,” Myrta, and began having an affair with Julia Smythe Conner. She was the wife of Alex Conner, who had moved into Holmes’ building and began working as a bookkeeper and at his pharmacy’s jewelry counter. After Conner found out about Julia’s affair with Holmes, he quit his job and left Julia and her daughter Pearl behind. Julia and Pearl remained at the hotel, and she continued her relationship with Holmes. Around Christmas of 1891, Julia and Pearl disappeared. They were most likely his first known murders. Holmes would later claim that Julia had died during an abortion, though what truly happened to the two was never confirmed.

In 1892, Holmes added a third floor to his building, telling investors and suppliers that he intended to use it as a hotel during the upcoming World’s Columbian Exposition. However, the hotel portion was never completed. Furniture suppliers found that Holmes was hiding their materials, for which he had never paid, in hidden rooms and passages throughout the building. Their search made the news, and investors for the planned hotel pulled out of the deal.

In May 1892, another girl named Emeline Cigrande began working in the building and disappeared in December. Another neighborhood girl by the name of Edna Van Tassel also “vanished” at about the same time and was thought to have been another potential victim.

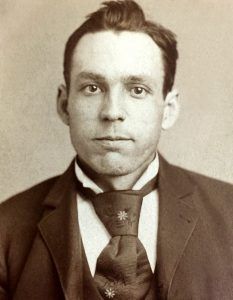

In the meantime, Holmes made the acquaintance of Benjamin Pitezel when he placed an ad in search of carpenters. Pitezel was also a petty criminal and alcoholic. Despite his issues, the two became close friends, and Pitezel would quickly become Holme’s right-hand man for several criminal schemes.

In early 1893, a one-time actress named Minnie Williams moved to Chicago, and Holmes offered her a job at the hotel as his personal secretary. Williams owned some property in Fort Worth, Texas, that Holmes convinced her to sign over to him. Holmes later transferred the deed to Pitezel. In May of 1893, Holmes and Williams rented an apartment in Chicago’s Lincoln Park, presenting themselves as man and wife. Minnie’s sister, Nannie, came to visit, and in July, she wrote to her aunt that she planned to accompany “Brother Harry” to Europe. Neither Minnie nor Nannie were seen alive after July 5, 1893.

In 1893, Chicago was honored to host the World’s Fair, a cultural and social event to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of America. The event was scheduled to take place from May to October and attracted thousands of people worldwide. During this time, Holmes opened up his home as a hotel for visitors. Some would never be seen again.

Holmes advertised in the newspaper to best take advantage of Chicago’s influx of tourists. In these ads, he called the castle, which was only a few miles away from the fairgrounds, the “World’s Fair Hotel.” Holmes not only ensnared soon-to-be victims by newspaper ads, but he also attended the fair in the company of the Pitezel children. There, the impeccably dressed doctor would turn on the charm, luring wealthy women to his castle with the promise of a good night’s rest. Usually from out of town and unnoticed in the huge fair crowds, they were impossible to trace once they vanished into the castle’s dark recesses. The list of the “missing” when the Fair closed was long, and for most, foul play was suspected. How many of them fell prey to Holmes is a mystery, but no fewer than 50 people who were reported to the police as missing were traced to the castle, where their trails ended.

Chicago World’s Fair 1893

On August 13, 1893, the third floor of Holmes’ building caught fire. Luckily, only a few people were in the building – all employees and long-term residents who could get out. Holmes had taken out insurance policies on the building with at least four companies, who promptly sued rather than pay.

With insurance companies pressing to prosecute Holmes for arson, Holmes left Chicago in July 1894. He reappeared in Fort Worth, looking to build on the property that Minnie Williams had transferred. That same month, however, he was arrested and briefly incarcerated for the first time on the charge of selling mortgaged goods in St. Louis, Missouri.

While in jail, he struck up a conversation with a convicted outlaw, Marion Hedgepeth, who was serving a 25-year sentence. Holmes had concocted a plan to swindle an insurance company out of $10,000 by taking out a policy on himself and then faking his death. Holmes promised Hedgepeth a $500 commission in exchange for the name of a lawyer who could be trusted. Given the name of Jeptha Howe, Holmes began planning his own death after he was released on bail. However, the plan failed when the insurance company became suspicious and refused to pay. Holmes did not press the claim; instead, he concocted a similar plan with his friend, Benjamin Pitezel.

Pitezel agreed to fake his own death so that his wife could collect on a $10,000 life insurance policy, which was to be split with Holmes and attorney Jeptha Howe. The scheme, which was to take place in Philadelphia, called for Pitezel to set himself up as an inventor under the name B.F. Perry, and then be killed and disfigured in a lab explosion. Holmes was to find an appropriate cadaver to play the role of Pitezel.

Instead, Holmes killed Pitezel by knocking him unconscious with chloroform and setting his body on fire. Holmes proceeded to collect the insurance payout based on the genuine Pitezel corpse. He then went on to manipulate Pitezel’s unsuspecting wife into allowing three of her five children to be in his custody. The eldest daughter and the baby remained with Mrs. Pitezel while Holmes and the three Pitezel children traveled throughout the northern United States and into Canada. Simultaneously, he escorted Mrs. Pitezel along a parallel route, all the while using various aliases and lying to Mrs. Pitezel concerning her husband’s death, claiming that her husband was in London.

Holmes would later confess to murdering two of the children by forcing them into a large trunk, drilling a hole in the trunk, and attaching a gas line to asphyxiate the girls. Holmes buried their nude bodies in the cellar of his rental house in Toronto. Frank Geyer, a Philadelphia detective tracking Holmes, found the decomposed bodies of the two Pitezel girls in the Toronto basement.

Geyer then followed Holmes to Indianapolis, where Holmes had rented a cottage. Holmes was reported to have visited a local pharmacy to purchase the drugs that he used to kill the third Pitezel child and a repair shop to sharpen the knives he used to chop up the body before he burned it. The boy’s teeth and bits of bone were discovered in the home’s chimney.

On January 17, 1894, Holmes married for a third time to Georgiana Yoke in Denver, Colorado. He was still legally married to both Clara and Myrta.

In the meantime, Marion Hedgepath, who was angry that he did not receive any money in the “faked death” scam, told police about the fraud that Holmes had planned. Afterward, the authorities doubled their efforts to find the elusive killer.

Holmes’ murder spree finally ended when he was arrested in Boston, Massachusetts, on November 17, 1894, after being tracked there from Philadelphia by the Pinkertons. He was held on an outstanding warrant for horse theft in Texas, as the authorities had become more suspicious at this point, and Holmes appeared poised to flee the country in the company of his unsuspecting third wife.

During his time in custody, Holmes initially claimed to be nothing but an insurance fraudster, admitting to using cadavers to defraud life insurance companies several times in college. But, over time, his stories changed once he admitted to killing 28 people. Other estimates range from 20 to as many as 200 victims. While he was incarcerated, Holmes was paid $7,500 (worth about $216,000 today) by the Hearst newspapers in exchange for his confession, much of which was found to be lies. Holmes gave various contradictory accounts of his life, initially claiming innocence and later that Satan possessed him. His many lies made it difficult for investigators to determine the truth.

With Holmes behind bars, Chicago police began to investigate Holmes’ building. The ground floor of the building was divided into ordinary retail spaces, including a jewelry store, pharmacy, blacksmith shop, barber, and restaurant. The third floor comprised apartments, offices, and Holmes’ living quarters. But they discovered an elaborate house of horrors on the second floor and basement.

The second floor was a maze of some 35 small windowless rooms, stairs, doors that led nowhere, false partitions, trap doors, secret passageways, and a staircase that opened over a steep drop to the alley behind the house. Some trapdoors and dumbwaiters enabled him to move the bodies down to the basement. Some rooms were soundproof and had peepholes enabling Holmes to monitor their interiors. Others were connected to a gas line where victims could be asphyxiated.

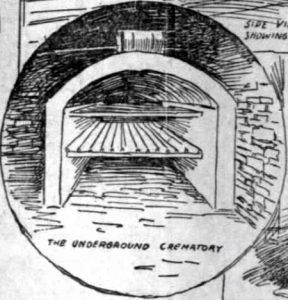

The basement held a crematorium, a blood-spattered dissection table, vats of acid, surgical implements, various jars of poison, pits of quicklime, and torture devices attached to the walls. Holmes is thought to have stripped many of the bodies down to their skeletons to sell them for medical study.

Not only did they find the equipment to produce evil, but they also found large quantities of human bones, tufts of hair, bloodstained linen, and pieces of clothing that appeared to have been hastily concealed. Portions of bodies were so badly dismembered and decomposed that it was hard for them to determine exactly how many bodies there really were.

The building soon became known as the “Murder Castle.”

After a trial in which he acted as his own attorney, Holmes was sentenced to death for the murder of Benjamin Pitezel in 1895. Holmes appealed his case but lost. Though Canada and Illinois both tried to extradite Holmes from Pennsylvania, he was executed. He met his end on May 7, 1896, when he was hanged for the Pitezel murder in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Until the moment of his death, Holmes remained calm and amiable, showing very few signs of fear, anxiety, or depression. During the hanging, Holmes’ neck did not snap; he instead was strangled to death slowly, twitching for over 15 minutes before being pronounced dead 20 minutes after the trap had been sprung.

Holmes asked for his coffin to be contained in cement and buried 10 feet deep because he was concerned grave robbers would steal his body and use it for dissection.

Holmes’s life as one of America’s first serial killers has been the subject of many books, documentaries, and a feature film.

The Castle itself was mysteriously gutted by fire in August 1895. According to a newspaper clipping from the New York Times, two men were seen entering the back of the building between 8 and 9 p.m. About half an hour later, they were seen exiting the building and rapidly running away. Following several explosions, the Castle went up in flames. Afterward, investigators found a half-empty gas can underneath the back steps of the building. The building survived the fire and remained in use until it was torn down in 1938. The Englewood branch of the United States Postal Service currently occupies the site.

In 2017, amid allegations that Holmes had, in fact, escaped execution, Holmes’ body was exhumed for testing. Due to his coffin being contained in cement, his body was found not to have decomposed normally. His clothes were almost perfectly preserved, and his mustache was found to be intact. The body was positively identified as being that of Holmes with his teeth. Holmes was then reburied.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Outlaw & Scoundrel Photo Galleries

Story of the Outlaw – Study of the Western Desperado

Sources:

Biography.com

Chicago Tribune, August 18, 1895

Harper’s Magazine Archive

Neatorama

Prairie Ghosts

Wikipedia