Fort Warren, Massachusetts, by Doc Searls, Flickr

“The horrors of imprisonment, close confinement, no one to see or talk to, with the reflection of being cut off for I know not how long and perhaps forever — from communication with dear ones at home, are beyond description. Words utterly fail to express the soul’s anguish.”

— Alexander H. Stephens, Vice-President of the Confederate States, 1865

Situated on Georges Island at the entrance to Boston Harbor in Massachusetts, Fort Warren was built between 1883 and 1861 and is best known for its service during the Civil War. It has also been long known for the ghostly “Lady in Black” that is said to roam its grounds.

Before Europeans arrived in America, the Boston Harbor Islands were utilized by Native Americans who fished and farmed. When English and European immigrants arrived in the 17th century, they focused on fishing and trade and built lighthouses and fortifications on the islands. At this point, Georges Island was first called Pemberton’s Island, named for its first owner, James Pemberton, who began living on the island in 1628. Early in the 18th century, the island was renamed Georges Island for Captain John George, a prominent Boston merchant and town official.

During the American Revolution, John Adams was one of several political and military leaders who recognized the military importance of Georges Island, which guarded the Narrows, the main shipping channel into Boston. Although the British Army had evacuated Boston in March 1776, British ships remained at Nantasket, posing a threat of reinvasion. In 1778, our French allies built temporary earthworks on Georges Island to protect their fleet and defend Boston from possible British attack.

In 1825, the City of Boston bought Georges Island and turned it over to the United States Government. From 1825-1832, the government constructed a seawall around the island to control erosion. In 1834, Colonel Sylvanus Thayer of the United States Army Corps of Engineers and former superintendent of West Point began supervising the construction of Fort Warren, named for Dr. Joseph Warren, the Revolutionary War patriot killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

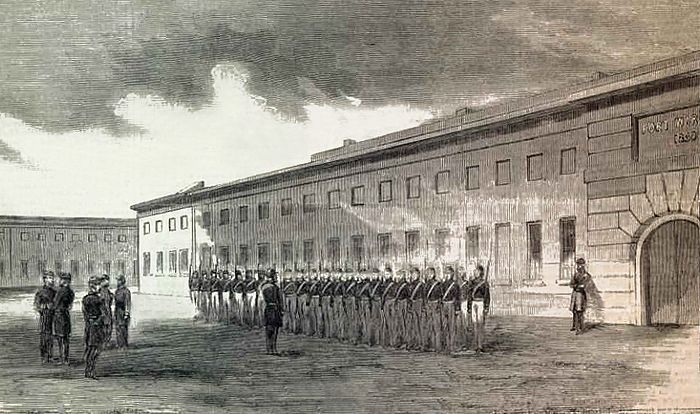

The large pentagonal bastion fort was built with granite and other stone quarried from Quincy and Cape Ann. It was largely finished by 1858, but when the Civil War broke out in April 1861, there was still construction debris on the parade ground, and no guns were mounted. At that point, Massachusetts Governor John Andrew and the Legislature were critical in organizing heavy artillery companies to garrison Fort Warren. It was the fifth largest of the 42 third-system forts. When complete, the fort had five bastions that increased firepower along the walls. Additional guns were mounted in casemates and interior rooms within the fort’s walls and fired through openings called embrasures. Guns were also mounted on the terreplein, or roof level, atop the casemates.

During the Civil War, Fort Warren served as Boston’s main line of defense against invasion by the Confederate Navy, as a recruiting and training camp for Union soldiers, and, most importantly, as a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp for military and political prisoners. The first prisoners were sent to the island in October 1861, which included 155 political prisoners and over 600 military prisoners.

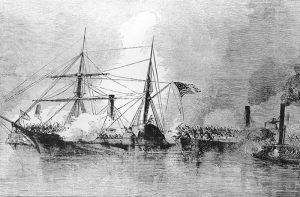

During the Civil War, Fort Warren’s prisoners included the mayor of Baltimore, Maryland, the governor of Kentucky, and several members of the Maryland Legislature. In November 1861, two Confederate diplomats — James Murray Mason and John Slidell, were removed from a British ship by the Union Navy and held at Fort Warren until January 1862. The highest-ranking prisoner was Alexander H. Stephens, Vice-President of the Confederacy, who was imprisoned there from May to October 1865.

The prison camp had a reputation for humane treatment of its detainees. Though many complained about overcrowding and poor food, Fort Warren’s living conditions were far superior to Confederate prisoner-of-war camps. Under the command of Colonel Justin Dimick and his successors, Fort Warren recorded only 13 deaths among the more than 1,000 prisoners confined there during the war.

The development of longer-range artillery and new weapons after the Civil War resulted in new construction and military uses for Fort Warren. Updated gun batteries were installed in the 1890s. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, mines were established in Boston Harbor, and Fort Warren returned to active military service.

In the years before World War I, a mine storage building and an observation tower were built, and Fort Warren served as a mine command center during the war. Just before World War II, an archway was added that extended from the Guard House to a concrete structure that served as a mine control center in anticipation of potential attacks by German U-boats. At that time, Fort Warren was garrisoned by the 241st Coast Artillery Regiment, a Massachusetts National Guard unit that was federalized in September 1940.

Fort Warren, Massachusetts by Rob Duch, Wikipedia

Fort Warren was decommissioned in 1946 and designated a National Historic Site in 1958. At that time, Georges Island was owned and operated by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and became one of 17 islands that became part of Boston Harbor Islands State Park. After some restoration, the fort was opened to the public in 1961. Since 1996, Georges Island has also been part of Boston Harbor Islands National Park, a partnership of national, state, and local representatives.

No shots were ever fired in anger from the fort.

The fort is also said to be haunted by several ghostly spirits. Strange lights and sounds are seen, including footsteps, when no one is present. Staff and visitors have seen unearthly shadowy and misty figures and other apparitions in Civil War Uniforms, some of which have been caught on camera. Others report unseen entities touching them, smelling vintage perfume, and hearing moaning and voices.

There have been reports of hearing the sound of the song John Brown’s Body on the harmonica, which soldiers often played at the fort. Footsteps that come from nowhere and go nowhere have been found in the snow. Stones have been observed rolling across rooms seemingly of their own accord.

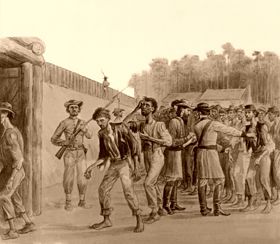

The fort’s most famous legend is the “Lady in Black,” a ghostly apparition who is said to roam the post. According to the tale, in early 1862, a southern woman named Melanie Lanier, whose husband was a Confederate officer imprisoned at the fort, made a reckless attempt to free her newlywed husband. After she had heard he had been captured, she secured passage on a ship bound for Hull, Massachusetts, where she stayed at the home of a Confederate sympathizer. Somehow, she could send a message to her husband that she was planning his escape, and on the designated night, she rowed across about a mile of water from Hull to Georges Island.

Dressed as a man and carrying a pistol, she somehow entered the prison, where she was reunited with her husband. The couple then began to dig a tunnel and escape. However, their plans were foiled when they dug too close to a stone wall and were heard by the Union soldiers. As the Federal troops came upon the pair, Mrs. Lanier pointed her gun at them, but one of the men gained control of it. In the melee, the pistol accidentally went off, killing her husband. Afterward, Lanier was sentenced to death as a spy, and plans were made for her execution. Her last wish was to be hanged in a dress, and somehow, a black one was found for her.

After her death, many soldiers claimed to have seen the mysterious apparition of a “Lady in Black,” and her voice was heard in the Corridor of Dungeons. According to the tales, some were even court-martialed for shooting at a phantom in black, and one was brought up on charges for fleeing his post because she had chased him.

Her story was first documented in a 1944 book called The Romance of Boston Bay by Edward Rowe Snow, a historian and folklore writer. Though later historians and reporters have found no mention of a woman being hanged as a spy at Fort Warren, the legend persists, and both visitors and staff still report seeing her. Some say they have heard her screams.

Today, the fort is typically open from early or mid-May through Columbus Day weekend. Rangers offer guided tours, or visitors can explore on their own. There is a museum located in the old mine storehouse with information and exhibits that tell the history of the post.

The fort is reachable by ferry from downtown Boston, Hingham, or Hull to Georges Island. Transfers are then available for those who wish to visit some of the other Harbor Islands.

“Such duty on a bleak island, exposed to the terrible cold and storms of a New England winter, was no pastime.”

— Major Parker, First Battalion, Massachusetts Infantry, describing the harsh conditions during the winter of 1861-62

More Information:

George’s Island

15 State Street, Suite 1100

Boston, Massachusetts 02109

617-223-8666

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Forts & Presidios Across America

Forts & Presidios Photo Gallery

Sources:

Boston Boxer Hotel

Historical Digression

National Park Service

Wikipedia