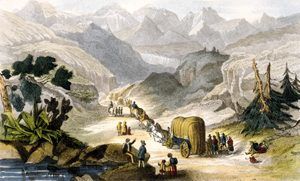

Emigrant party on the road to California

In 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in California and people from all over the United States packed their belongings and began to travel by wagon to what they hoped would be a new and better life. Since most of these pioneers began their exodus to California in 1849, they are generally referred to as ’49ers.

One of the supply points along the trail was Salt Lake City, Utah, where pioneers prepared for the long journey across the Great Basin desert before climbing over the Sierra Nevada to the goldfields of California. It was important to leave Salt Lake City and cross the desert before the snow began to fall on the Sierra Nevada, making them impassible. Only a couple of years before, a group of pioneers called the Donner Party was trapped by a storm, an event that became one of the greatest human disasters of that day and age. The stories of the Donner Party were still fresh on everyone’s mind when a group of wagons began their journey from Salt Lake City in October 1849. This was much too late to try to cross the Sierra Nevada safely, and it looked like these wagons were going to have to wait out the winter in Salt Lake City.

Old Spanish Trail

It was then that they heard about the Old Spanish Trail, a route that went around the south end of the Sierra Nevada and was safe to travel in the winter. The problems were that no pioneer wagon trains had traversed it and they could only find one person in town who knew the route and would agree to lead them. As they started their journey, no one knew that this wagon train — the San Joaquin Company — would become part of a story of human suffering in a place they named Death Valley.

The going was slower than most of the travelers wanted, but, the group’s guide, Captain Jefferson Hunt, would only go as fast as the slowest wagon in the group. Just as many of the pioneers were about to voice their dissent, a young man rode into camp and showed them a hand-sketched map of a fictitious “shortcut” across the desert to a place called Walker Pass. Everyone agreed that this would cut off 500 miles from their journey, so most of the 107 wagons decided to follow this purported shortcut, while the others continued along the Old Spanish Trail with Captain Hunt. The point where these wagons left the Old Spanish Trail was near the present-day town of Enterprise, Utah where a Jefferson Hunt Monument commemorates this historic event.

Soon after those following the “shortcut” began their journey, they came to a gaping canyon on the present-day Utah–Nevada state line. Most of them became discouraged and turned back to join Captain Hunt, but, more than 20 wagons decided to continue on. It was a tedious chore getting the wagons around the canyon and took several days. However, despite the fact that the group didn’t have a reliable map, they were sure they would eventually find a pass.

The group then traveled through the area of present-day Panaca, Nevada, and continued over summits and across barren valleys to Groom Lake, near the present-day town of Rachel. There, they got into a dispute on which way to go. One group — the Bennett-Arcan party — wanted to head south toward the distant, snow-clad Mt. Charleston in hopes of finding a good water source. The other group — the Jayhawkers — wanted to stay with the original plan of traveling directly west. The wagon train eventually split and went their separate ways, but, both groups were saved from dying of thirst by a snowstorm and both ended up in Death Valley. They entered the valley by way of present-day Death Valley Junction and along the same route followed by Highway 190 today. On Christmas Eve of 1849, some of them arrived at Travertine Springs, the source of Furnace Creek.

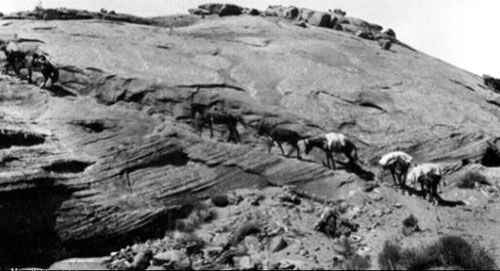

Panamint Mountains

The lost ’49ers had now been traveling across the desert for about two months since leaving the Old Spanish Trail. Their oxen were weak from lack of forage and their wagons were battered and in poor shape. The pioneers were weary and discouraged but, their worst problem was not the valley that lay before them – it was the towering Panamint Mountains that stood like an impenetrable wall as far as could be seen.

From Furnace Creek, the routes of the two groups diverged. The Jayhawkers, which included the Brier family and Lorenzo Dow Stephens, who would later write of the whole ordeal, went north toward the Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes where they decided they would have to leave their wagons and belongings behind and walk. They slaughtered several oxen and used the wood of their wagons to cook the meat and make jerky. After crossing the Panamint Mountains via Towne Pass and dropping down into Panamint Valley, most of them turned south, making their way into Indian Wells Valley near the present-day city of Ridgecrest, California. There, they followed a prominent Indian trail heading south to civilization.

In the meantime, the Bennett-Arcan party struggled across the salt flats and attempted to pass over the Panamint Range via Warm Springs Canyon, but, they were unable to do so. They retreated to the valley floor and sent two young men, William Lewis Manly and John Rogers, over the mountain to get supplies. Thinking the Panamint Range was the Sierra Nevada, some expected a speedy return. Instead, nearly a month went by as the men walked more than 300 miles to Mission San Fernando, got supplies at a ranch, and trecked back with three horses and a one-eyed mule.

Along the way, one of the horses was ridden to death and the other two had to be abandoned. When Manly and Rogers finally arrived at the camp of the Bennett-Arcan party, they found many of the group had left to find their own way out of the valley. Two families with children had patiently remained, trusting the men to save them. Only one man had perished during their long wait, but, as they made their way west over the mountains, someone is said to have proclaimed “Goodbye, Death Valley,” giving the valley its morbid name.

They may have escaped Death Valley, but it took another 23 days to cross the Mojave Desert and reach the safety of Rancho San Francisco in Santa Clarita Valley. The so-called “shortcut” that had lured the Lost ’49ers away from Captain Hunt’s wagon train had proved to take four months and cost the lives of many men through the entire ordeal.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated July 2021.

Also See:

The Jayhawker Journey – lllinois to California in 1849

Source: National Park Service