“I don’t smoke much, and I drink very little. I guess my only bad habit is robbing banks.”– John Dillinger

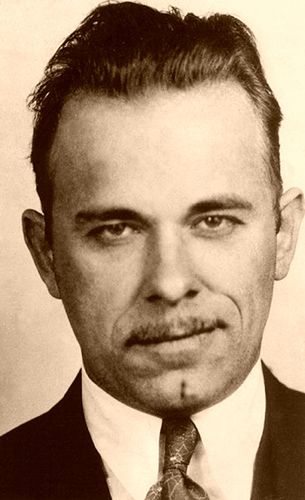

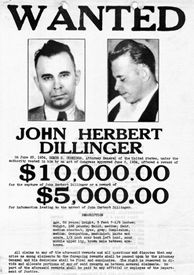

John Herbert Dillinger was a dangerous killer and midwestern bank robber during the early 1930s. He was responsible for the murder of several police officers, robbed at least two dozen banks, and escaped from jail twice.

During the Great Depression, many Americans, deep in poverty and feeling helpless, made heroes of outlaws who took what they wanted at gunpoint. Of all these many outlaws, John Herbert Dillinger came to evoke this Gangster Era and stirred mass emotion to a degree rarely seen in this country.

Idolizing him as a modern-day Robin Hood, Dillinger was nicknamed “the Jackrabbit” for his graceful movements during his robberies — such as leaping over counters and his many narrow escapes from the police.

The exploits of Dillinger and his gang, along with those of other criminals of the Great Depression such as Bonnie and Clyde and Ma Barker, dominated the attention of the American press and its readers during the Depression era, a period which led to the development of the modern, more sophisticated Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Dillinger was born on June 22, 1903, in Indianapolis, Indiana. Growing up in a middle-class residential neighborhood, his father, a hardworking grocer, raised him in an atmosphere of disciplinary extremes, harsh and repressive on some occasions but generous and permissive on others. John’s mother died when he was three, and when his father remarried six years later, John resented his stepmother.

As a teenager, he began to get in trouble, finally quitting school and getting a job in a machine shop in Indianapolis. Although intelligent and a good worker, he soon became bored and often stayed out all night. His father worried that the temptations of the city were corrupting the boy, so he sold his property in Indianapolis and moved his family to a farm near Mooresville, Indiana. However, John reacted no better to rural life than he had in the city and began to run wild again.

He was soon caught stealing a car, which led him to enlist in the Navy. There, he quickly got into trouble and deserted his ship when it docked in Boston, Massachusetts. Returning to Mooresville, he married 16-year-old Beryl Hovious in 1924. The pair moved to Indianapolis, but Dillinger could not find a job. He then hooked up with the town pool shark, Ed Singleton, in his search for easy money.

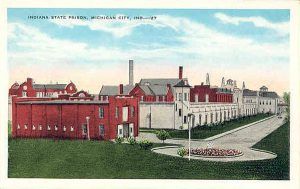

The hoodlums first tried to rob a Mooresville grocery store but were quickly apprehended. Singleton pled not guilty, stood trial, and was sentenced to two years. Following his father’s advice, Dillinger confessed and was convicted of assault and battery with intent to rob and conspiracy to commit a felony. He received joint sentences of 2 to 14 years and 10 to 20 years in the Indiana State Prison. Stunned by the harsh sentence, Dillinger became a tortured, bitter man in prison. His marriage ended in divorce in 1929.

Dillinger was paroled on May 10, 1933, after serving nine and a half years. In the midst of the Depression, he had little prospect of finding employment and immediately returned to crime. On June 10, 1933, he robbed his first bank, taking $10,000 from the New Carlisle National Bank in New Carlisle, Ohio. On August 14th, he robbed another bank in Bluffton, Ohio. Dayton police arrested him on September 22, and he was lodged in the county jail in Lima, Ohio, to await trial.

In frisking Dillinger, the Lima police found a document that seemed to be a plan for a prison break, but the prisoner denied knowledge of any plan. Four days later, using the same plans, eight of Dillinger’s friends escaped from the Indiana State Prison, using shotguns and rifles smuggled into their cells. During their escape, they shot two guards.

On October 12th, three of the escaped prisoners and a parolee from the same prison showed up at the Lima jail where Dillinger was incarcerated, pretending to be law enforcement officials. They told the sheriff that they had come to return Dillinger to the Indiana State Prison for violation of his parole. When the sheriff asked to see their credentials, one of the men pulled a gun, shot the sheriff, and beat him into unconsciousness. Then, taking the keys to the jail, the bandits freed Dillinger, locked the sheriff’s wife and a deputy in a cell, and, leaving the sheriff to die on the floor, made their getaway.

Although none of these men had violated federal law, the FBI’s assistance was requested in identifying and locating the criminals. The four men were Harry Pierpont, Russell Clark, Charles Makley, and Harry Copeland.

Members of the Dillinger Gang (from left) Russell Clark, Charles Makley, Harry Pierpont, John Dillinger, Ann Martin, and Mary Kinder are arraigned in a Tucson, Arizona courtroom. Photo courtesy the Associated Press.

In the meantime, the Dillinger Gang pulled several bank robberies and plundered the police arsenals at Auburn and Peru, Indiana, stealing several machine guns, rifles, revolvers, ammunition, and several bulletproof vests. On December 14th, John Hamilton, a Dillinger Gang member, shot and killed a police detective in Chicago. A month later, the Dillinger Gang killed a police officer during the First National Bank of East Chicago, Indiana robbery. Then they made their way to Florida and, subsequently, to Tucson, Arizona. On January 23, 1934, a fire broke out in the hotel where Clark and Makley were hiding under assumed names.

Firemen recognized the men from their photographs, and local police arrested them, as well as Dillinger and Harry Pierpont. They also seized three Thompson submachine guns, two Winchester rifles mounted as machine guns, five bulletproof vests, and more than $25,000 in cash, part of it from the East Chicago robbery.

Dillinger was sequestered at the county jail in Crown Point, Indiana to await trial for the murder of the East Chicago police officer. Though authorities boasted that the jail was “escape-proof,” Dillinger threatened the guards with what he claimed later was a wooden gun he had whittled and forced them to open his cell door on March 3, 1934. He grabbed two machine guns, locked up the guards and several trustees, and fled.

It was then that Dillinger made the mistake that would eventually cost him his life. He stole the sheriff’s car and drove across the Indiana-Illinois line, heading for Chicago. By doing that, he violated the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, which made it a federal offense to transport a stolen motor vehicle across a state line. Within no time, a federal complaint was sworn to charge Dillinger with the theft of the vehicle, which was recovered in Chicago. After the grand jury returned an indictment, the FBI became actively involved in the nationwide search for Dillinger.

Meanwhile, Pierpont, Makley, and Clark were returned to Ohio and convicted of the murder of the Lima sheriff. Pierpont and Makley were sentenced to death, and Clark to life imprisonment. But, in an escape attempt, Makley was killed and Pierpont was wounded. A month later, Pierpont had recovered sufficiently to be executed.

In Chicago, Dillinger joined his girlfriend, Evelyn Frechette. They proceeded to St. Paul, Minnesota where Dillinger teamed up with Homer Van Meter, Lester “Baby Face Nelson” Gillis, Eddie Green, and Tommy Carroll, among others. The gang’s business prospered as they continued robbing banks.

On March 30, 1934, an FBI Agent talked to the manager of the Lincoln Court Apartments in St. Paul, who reported two suspicious tenants using the names of Mr. and Mrs. Hellman. The manager reported that the residents acted nervously and refused to admit the apartment caretaker. The FBI quickly began a surveillance of the apartment and the next day, an agent and a police officer knocked on the door of the apartment. When Evelyn Frechette opened the door, she quickly slammed it shut and the agent called for reinforcements to surround the building.

On March 30, 1934, an FBI Agent talked to the manager of the Lincoln Court Apartments in St. Paul, who reported two suspicious tenants using the names of Mr. and Mrs. Hellman. The manager reported that the residents acted nervously and refused to admit the apartment caretaker. The FBI quickly began a surveillance of the apartment and the next day, an agent and a police officer knocked on the door of the apartment. When Evelyn Frechette opened the door, she quickly slammed it shut and the agent called for reinforcements to surround the building.

While waiting, the agents saw a man enter a hall near the Hellman’s apartment, who wound up being Homer Van Meter. When questioned, Van Meter drew a gun, and shots were exchanged. Van Meter then fled the building and forced a truck driver at gunpoint to drive him to Eddie Green’s apartment. Suddenly the door of the Hellman apartment opened, and the muzzle of a machine gun began spraying the hallway with lead. Under cover of the machine-gun fire, Dillinger and Evelyn Frechette fled through a back door. They, too, drove to Green’s apartment, where Dillinger was treated for a bullet wound.

At the Lincoln Court Apartments, the FBI found a Thompson submachine gun with the stock removed, two automatic rifles, one .38 caliber Colt automatic with twenty-shot magazine clips, and two bulletproof vests. Across town, other agents located one of Eddie Green’s hideouts where he and Bessie Skinner had been living as “Mr. and Mrs. Stephens.” On April 3rd, when Green was found, he attempted to draw his gun, but was shot by the agents and died in a hospital eight days later.

Dillinger and Evelyn Frechette fled to Mooresville, Indiana, where they stayed with his father and half-brother until his wound healed. Frechette then went to Chicago to visit a friend and was arrested by the FBI. She was taken to St. Paul, Minnesota for trial on a charge of conspiracy to harbor a fugitive. She was convicted, fined $1,000, and sentenced to two years in prison. Bessie Skinner, Eddie Green’s girlfriend, got 15 months on the same charge.

Meanwhile, Dillinger and Van Meter robbed a police station at Warsaw, Indiana of guns and bulletproof vests. Dillinger stayed for a while in Upper Michigan, departing just ahead of a posse of FBI Agents. A short time later, the FBI received a tip that there had been a sudden influx of rather suspicious guests at the summer resort of Little Bohemia Lodge, about 50 miles north of Rhinelander, Wisconsin. One sounded like John Dillinger and another like “Baby Face Nelson.”

From Rhinelander, an FBI task force set out by car for Little Bohemia. Two miles from the resort, the car lights were turned off and the posse proceeded through the darkness. When the cars reached the resort, dogs began barking. The agents spread out to surround the lodge, and as they approached, machine gun fire rattled down on them from the roof. Swiftly, the agents took cover and one of them hurried to a telephone to give directions to additional agents who had arrived in Rhinelander to back up the operation.

While the agent was telephoning, the operator broke in to tell him there was trouble at another cottage about two miles away. Special Agent W. Carter Baum and a constable went there and found a parked car which the constable recognized as belonging to a local resident. They pulled up and identified themselves.

Dillinger and his gang hid out at Little Bohemia, Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin. An all-out gun battle occurred here in which two men were killed, and four wounded as the gang escaped.

Inside the other car, “Baby Face Nelson” held three local residents at gunpoint. He turned, leveled a revolver at the lawmen’s car, and ordered them to step out. But without waiting for them to comply, Nelson opened fire. Baum was killed, and the constable and the other agent were severely wounded. Nelson jumped into the Ford they had been using and fled.

Dillinger was gone when the firing had subsided at the Little Bohemia Lodge. When the agents entered the lodge the next morning, they found only three frightened females. Dillinger and five others had fled through a back window before the agents surrounded the house.

In Washington, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover assigned Special Agent Samuel A. Cowley to head the FBI’s efforts against Dillinger. Cowley soon set up headquarters in Chicago, where he and Melvin Purvis, Special Agent in Charge of the Chicago office, planned their strategy.

Late in the afternoon of Saturday, July 21, 1934, the madam of a brothel in Gary, Indiana, contacted one of the police officers with information. The woman, who called herself Anna Sage, but was actually Ana Cumpanas, had entered the United States from her native Rumania in 1914. Because of the nature of her profession, she was considered an undesirable alien by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and deportation proceedings had been started. Anna was willing to sell the FBI some information about Dillinger for a cash reward, plus the FBI’s help preventing her deportation.

At a meeting with Anna, Cowley and Purvis were cautious. They promised her the reward if her information led to Dillinger’s capture, but said all they could do was call her cooperation to the attention of the Department of Labor, which at that time handled deportation matters. Satisfied, Anna told the agents that a girlfriend of hers, Polly Hamilton, had visited her establishment with Dillinger. Anna had recognized Dillinger from a newspaper photograph.

Anna told the Agents that Polly Hamilton and Dillinger probably would be going to the movies the following evening at either the Biograph or the Marbro Theaters in Chicago. She said that she would notify them when the theater was chosen. She also said that she would wear an orange dress so that they could identify her.

On Sunday, July 22nd, Special Agent Samuel A. Cowley ordered all agents of the Chicago office to stand by for urgent duty. Anna Sage called that evening to confirm the plans, but she still did not know which theater they would attend. Therefore, agents and policemen were sent to both theaters. At 8:30 p.m., Anna Sage, John Dillinger, and Polly Hamilton strolled into the Biograph Theater to see Clark Gable in Manhattan Melodrama. Purvis phoned Cowley, who shifted the other men from the Marbro to the Biograph.

Cowley also phoned Hoover for instructions, who cautioned them to wait outside rather than risk a shooting match inside the crowded theater. Each man was instructed not to unnecessarily endanger himself and was told that if Dillinger offered any resistance, it would be each man for himself. At 10:30 p.m., Dillinger walked out of the theater with his two female companions on either side. As they walked past the doorway in which Purvis was standing, the agent lit a cigar to signal the other men to close in. Dillinger quickly realized what was happening and acted by instinct. He grabbed a pistol from his right trouser pocket as he ran toward the alley. Five shots were fired from the guns of three FBI Agents. Three of the shots hit Dillinger, and he fell face down on the pavement. At 10:50 p.m. on July 22, 1934, John Dillinger was pronounced dead in a little room in the Alexian Brothers Hospital.

The Agents who fired at Dillinger were Charles B. Winstead, Clarence O. Hurt, and Herman E. Hollis. Each man was commended by J. Edgar Hoover for fearlessness and courageous action. None of them ever said who actually killed Dillinger. The events of that July night in Chicago marked the beginning of the end of the Gangster Era. Eventually, 27 persons were convicted in Federal courts on charges of harboring and aiding and abetting John Dillinger and his gang members during their reign of terror. “Baby Face Nelson” was fatally wounded on November 27, 1934, in a gun battle with FBI Agents in which Special Agents Cowley and Hollis also were killed. Dillinger was buried in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana.

From September 1933 until July 1934, he and his violent gang killed ten men and wounded seven others.

But, was he really killed, or was it all a mistake?

Controversy over Dillinger’s Death

From the beginning, there were rumors that the FBI had shot the wrong guy. Instead, some people of the time, as well as today, believe that the man who was killed was a small-time hood named Jimmy Lawrence who had been set up to take the hit. Mysteriously, on the same night that Dillinger was allegedly shot, Lawrence disappeared. Eyewitnesses and even Dillinger’s father said the dead man was not John Dillinger. Autopsy reports were questioned and went missing.

Before the shooting, John Dillinger was known to have sometimes used the alias of “Jimmy Lawrence,” a man who coincidentally bore him a striking resemblance. Jimmy Lawrence was a petty Chicago criminal who had recently moved from Wisconsin. He lived in the same neighborhood as Dillinger and was known to frequent the Biograph Theater. After the shooting, a photograph was taken from Dillinger’s girlfriend, Polly Hamilton’s purse showing her in the company of a man who looks like the man killed at the Biograph, which happens to look very much like the “real” Jimmy Lawrence. Mysteriously, after Dillinger was allegedly shot, Jimmy Lawrence was never seen again.

After the shooting, the body was taken to the Cook County morgue for an autopsy. Though the corpse had a gunshot to the side of the face, witnesses would say that it did not look like the notorious gangster, John Dillinger. Furthermore, the first words from Dillinger’s father upon identifying the body were, “that’s not my boy.” Autopsy reports made no sense. The corpse was too tall and too heavy, the eye color was wrong, and it possessed a rheumatic heart, which was not a condition from which Dillinger suffered. Even the fingerprints on the body didn’t match.

The report indicated that the dead man had brown eyes, while Dillinger’s were gray. The Cook County medical examiner, Dr. Robert Stein, would say that the eyes become cloudy after death and that color is sometimes hard to determine. The report noted that the corpse had a rheumatic heart condition since childhood, but Dillinger had served in the Navy, where his service records showed that his heart was in perfect condition. Known scars and moles were not reported on the autopsy and the fingerprints didn’t match; but the FBI said these were altered during plastic surgery. A close up of the corpse’s face showed a full set of front teeth, but Dillinger was missing his front right incisor. Then the autopsy report went missing for some 50 years.

Respected crime writer Jay Robert Nash in his book, The Dillinger Dossier, lays out much information supporting the theory that Dillinger was not killed. He also contends that Chicago Police officer Martin Zarkovich; Louis Piquette, Dillingers’ lawyer; his girlfriend, Polly Hamilton, and her friend, Anna Sage, were all involved in the intricate plot. Might Polly Hamilton have made a date with Jimmy Lawrence to go to the Biograph, knowing that the FBI was waiting?

Other events also led to questions including the fact that the Indianapolis Star and the Little Bohemia Lodge received letters from a sender claiming to be John Dillinger in 1963. Later, a gun that had been on display for years at the FBI headquarters that was allegedly used by Dillinger against FBI agents outside of the Biograph Theater was proven not to belong to him. In fact, it had been manufactured years after his death. The original gun has never been recovered.

The FBI stood by its story, but the rumors have long persisted. Some believe the FBI agents covered it up, fearing the wrath of J. Edgar Hoover, who told them to “get Dillinger or else.” Alternatively, it may have been Hoover himself who was behind the cover-up. At the time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation was a relatively new agency, and if they had shot the wrong man, it would have been the third innocent man killed in pursuit of Dillinger.

In 1984, the autopsy records were finally found by an office worker stuffed in a shopping bag in a corner at the old county morgue. Spurring renewed interest, an exhumation was even talked about, but Dillinger’s body had been buried under five feet of concrete and steel. In 2006, the Discovery Channel explored the case by bringing in a team of experts to examine the autopsy and other evidence. They concluded that it was, in fact, John Dillinger who was killed by the FBI.

So, if they are wrong, and he lived, what happened to the real John Dillinger? Some claim that he married and moved to Oregon, disappearing once again in the late 1940s, never to be heard from again. Robert Nash; however, contends that Dillinger moved to California where he worked as a machinist under what would have been an early form of the witness protection program.

Legends of Hidden Loot

After serving some 9½ years in an Indiana prison, Dillinger was paroled in May 1933, the country was in the midst of the Great Depression and he had little prospect of finding employment. He soon returned to a life of crime, robbing his first bank on June 10, 1933. For the next year, he and his gang would rob at least a dozen banks, netting about $500,000, roughly equivalent to about $7 million in modern-day currency. Though Dillinger lived large and had to share the wealth with his partners in crime, that was a lot of money during 1933-1934.

It didn’t take long after Dillinger’s death before rumors circulated that he had hidden some of his ill-gained wealth. One of the first was that when John was hiding out at the Little Bohemia Lodge in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin in April 1934, he was in possession of some $200,000 in cash. Just two days after he and his gang arrived, they were ambushed by FBI agents on April 22nd and a shootout occurred in which Lester “Baby Face Nelson” killed a special agent and wounded two other men, while the agents accidentally killed a tavern customer and wounded two others. In the meantime, the criminals escaped. As the legend goes, Dillinger, making a run for it, was carrying the cash inside a suitcase which he buried in the woods a few hundred yards north of the lodge. Three months later, Dillinger was dead, and according to the legend, he was never able to return to Wisconsin to retrieve his buried cash.

Another legend began circulating after Harry Pierpont was executed at the old Ohio Penitentiary in October 1934. As the story goes, the Dillinger Gang had buried the loot from one of their bank robberies on the Pierpont farm. After the bank robbery, the gang had taken refuge at the homestead, but with the lawmen in hot pursuit, they buried the loot in a wooded area not far from the farmhouse and fled the property via a back road. Evidently, the rumor was enough for even the FBI at the time, as locals have said that agents hid in the cornfields near the farm after Harry Pierpont’s execution, waiting to see if anyone would return for the hidden cash. However, the time was wasted, as no one appeared to collect it. For years, people searched the property, looking for the cash, but if anything was ever found, it was not reported.

Today there is nothing left of the original Pierpont farm. The original farmhouse was moved off the property and later burned down. The barns and outbuildings were also torn down to make way for farm ground. The old farm is located on County Road 65 near the town of Leipsic in Putnam County, Ohio.

A third story, supposedly stated by the FBI, was that Dillinger had buried some $25,000 at his father’s 57-acre farm near Mooresville, Indiana.

Though many believe that one or more of these legends may be true, most historians say they are nothing but legends, and if true, the cash would have long disintegrated by now.

In any case, it makes the mystery even more interesting. If Dillinger wasn’t the man who was actually killed, did he, perhaps, return for the cash to fund a new lifestyle? We will never know.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Also See:

The FBI and the American Gangster

History of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Prohibition and Depression Era Gangsters

Sources:

Federal Bureau of Investigation

History.com

Nash, Jay Robert; The Dillinger Dossier, December Press, 1983

Weird Chicago

Wikipedia

Yocum, Robin; Chicago Tribune; February 1988