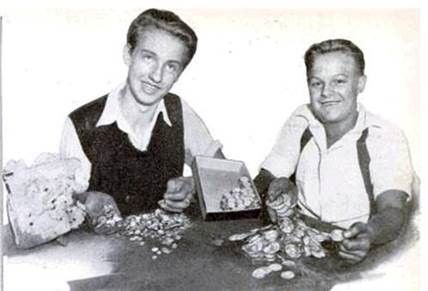

Henry Grob and Theodore Jones showing off their find.

By Jack Myers

Imagine finding 5,000 gold coins in a pot buried under your house! Inconceivable, right? But that happened to two Baltimore, Maryland, boys in 1934. The coins (at least most of them) were handed over to the police, and a prolonged legal battle ensued between the boys and the elderly landlords who owned the crumbling, inner-city tenement house. In the end, young Henry Grob and Theodore Jones prevailed, with the coins being sold at auction and the proceeds (after expenses) being put into trust until the teens reached age 21.

For the past 80+ years, it has been assumed that the golden fortune belonged to some unfortunate miser who had passed on without revealing to anyone where the treasure had been stashed. However, new evidence has recently surfaced that points directly to a secret Confederate society known as the Knights of the Golden Circle (K.G.C.) as the source of the immense treasure, worth more than $10 million in today’s economy.

The Knights were one of the country’s more successful “Southern Rights Clubs,” which agitated for more political power for the South. They opposed the abolitionists, Northern churches, and other Yankee movements that sought to “interfere” with the Southern economy, society, and way of life. The K.G.C. sought to have newly freed slaves returned to Africa, and they opposed the international ban on the African slave trade that exported additional slaves from that continent. Captain John J. Mattison, one of the 19th-century owners of the treasure house on Baltimore’s South Eden Street, had his own ship, the Eliza Davidson, seized off the coast of Sierra Leone for such illegal activity.

K.G.C. members also sought to add new slaveholding territories through the peculiar 19th-century institution known as “filibustering.” When Texas was annexed from Mexico by slave-owning Americans and added to the Union as a newly minted slave state, other Southerners saw an entrepreneurial opportunity of immeasurable proportions. Plots were hatched to invade Cuba, Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua, and other lightly-defended Latin American countries. All were squashed, foiled, or fell apart before being launched. The K.G.C., which boasted some 3,000 members in Baltimore alone, was known to collect dues and initiation fees in gold coinage. Some of that money was set aside (buried) in anticipation of funding Latin American expeditions that never materialized.

With the national rise to power of Abraham Lincoln and his Republican Party, the K.G.C. soon found a new enemy to oppose. The K.G.C. sought to keep Lincoln from getting to the White House, even if it meant assassinating him on his ride to the inauguration in Washington, D.C., in 1861. And if that drastic plan failed, the K.G.C. would spring into action to bring about Southern secession and the formation of the Confederate States of America.

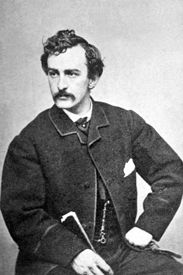

John Wilkes Booth.

One of the angry Baltimoreans who joined the K.G.C. as Lincoln was ascending to power was a hot-blooded young thespian named John Wilkes Booth. Booth had lived on Exeter Street and is said to have been inducted into the K.G.C. during a ceremony at a house “in his neighborhood.” Many top Baltimore officials are said to have attended Booth’s swearing-in in the house’s parlor, decorated with busts and paintings of Southern politicians and heroes. Booth took a solemn oath to protect the South and the new Confederacy at all costs. Not by chance, on South Central Avenue at this time, just 4/10th of a mile from Booth’s home lived a candle and soap company executive named Andrew Saulsbury. Saulsbury was an “ardent” Southern sympathizer whose home’s parlor would later be identified as having paintings of Confederate heroes adorning the walls. We know this because Saulsbury’s daughter would testify to this as an elderly woman at the 1935 trial for ownership of the 5,000 gold coins. Captain Mattison, the secret slaver, lived just around the corner from Southern sympathizer Saulsbury on adjoining Eden Street, the site of the 5,000 gold coins.

At the war’s end, Saulsbury would buy the Eden Street treasure home from secret slaver Captain Mattison, his rebel brother-in-arms.

Saulsbury was employed by James Armstrong & Associates, makers of fine soaps and candles. The company’s main factory sat just off Pratt Street by the Inner Harbor, where Captain Mattison docked his ships, and slaves were held in pens to be “sold South.” Saulsbury felt so indebted to the Armstrongs that he named his first-born son James Armstrong Saulsbury.

James Armstrong expanded his business in the 1840s by merging with the rival candle and soap firm Charles Webb and Sons. The senior Webb had passed away, leaving sons Charles, Jr. and James in charge. Later, during the 1850s, businessman Armstrong expanded his empire by opening a downtown insurance firm specializing in insuring ships’ cargo. The board of directors of that insurance company included old man Armstrong himself, Charles Webb, Jr., James Webb, and retired ship captain John J. Mattison. Armstrong would soon leave the running of the soap and candle enterprise to his trusted young executives Charles Webb, Jr., James Webb, Andrew Saulsbury, and nephew Thomas Armstrong.

Charles Webb.

Charles Webb and his brother James were high-ranking Freemasons, with Charles selected to be Maryland’s youngest-ever Grand Master of Freemasonry in 1853. His sponsor and “Companion” Mason was the powerful Albert Pike from Arkansas, soon to be the supreme commander of all Southern Freemasons … and the suspected national leader of the Knights of the Golden Circle.

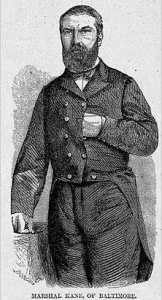

Charles Webb was also a political kingmaker in Baltimore for the Southern Democrats, the party that opposed Lincoln and promoted the continuation of slavery. In 1859-60, he backed the like-minded George Brown for Mayor and the fiery slave-owning Lincoln-hating George P. Kane for the position of police marshal.

Andrew Saulsbury, who bought the Eden Street treasure home from Captain Mattison, would one day have a grandson named Charles Webb Saulsbury.

Fellow candle executive Thomas Armstrong, the company founder’s nephew, lived at a local hotel known as the Fountain Hotel. Known as something of a “rebel” hangout, the establishment had also been the haunt of the young John Wilkes Booth. Many plots would be hatched at The Fountain, including those to infect the North with a yellow fever epidemic. Years after the war, when the hotel was torn down to make way for a much larger hotel, a box containing 2,000 gold coins would be discovered hidden on the premises.

Andrew Saulsbury would one day have yet another grandson, this one named Thomas Armstrong Saulsbury. Armstrong, Saulsbury, and the Webbs just weren’t fellow employees. They were blood brothers in unison for a cause, the Confederate States of America.

To recap, Charles Webb, a Southern Democrat-sponsored as Grand Master of Maryland Freemasonry by K.G.C. mastermind Albert Pike, had two employees and a fellow Armstrong board member all living with thousands of gold coins buried under their respective residences.

Fountain Inn, Baltimore, Maryland.

Could this somehow all be a coincidence??

In 1861, this country’s situation became highly volatile as the newly elected “Abolitionist” President prepared to take office.

As Abraham Lincoln’s train and entourage left Springfield, Illinois, on its several-day winding journey across the country toward its eventual final stop in Washington, D.C., alarm bells started to go off. A New York railroad C.E.O. heard rumors that a plot was afoot to murder Lincoln in Baltimore before he could ever reach the White House. That C.E.O. sent undercover New York City detectives to Baltimore to root out the conspiracy. The place they chose to stay, disguising themselves as rebel hotheads, was The Fountain Hotel.

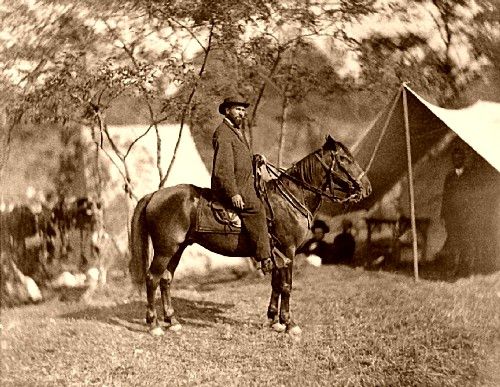

Meanwhile, Lincoln’s advisors were being given the same terrifying information. Lincoln would be targeted by K.G.C. assassins in Baltimore. They hired Allan Pinkerton and his Pinkerton Detective Agency to spy on the Baltimore conspirators.

Both investigative teams came to the same startling conclusion — Lincoln would almost certainly be murdered if he attempted to travel through Baltimore. Pinkerton’s report included the astonishing detail that Marshal Kane himself was likely involved with the plot — or at least would offer Lincoln little or no protection because of his loyalty to the rebel cause.

Pinkerton persuaded Lincoln to allow him to surreptitiously sneak the President-elect through Baltimore in the dead of night, allowing Abe to arrive at the White House quietly and safely.

But war itself was not averted. One by one, as the Southern states began to secede, a startled Lincoln ordered Northern troops from Pennsylvania and Massachusetts to hurry south to protect Washington, D.C. The Problem was that the troops were viciously attacked in Baltimore as they passed over the Pratt Street Bridge. The scene of the confrontation and following riot began at the foot of Concord Street, in front of the offices of James Armstrong & Associates, where Armstrong, Saulsbury, and Webb were all employed.

That evening, an incensed Marshal Kane, a close friend and political associate of Charles Webb, fired off this incendiary telegraph to the Maryland militia:

“Streets red with Maryland blood; send expresses over the mountains of Maryland and Virginia for the riflemen to come without delay. Fresh hordes will be down on us tomorrow. We will fight them and whip them or die.”

True to his word, Kane rounded up a party of rebels that evening to burn bridges and tear up the track leading from the North. Eyewitness evidence says a young John Wilkes Booth was an enthused participant.

Lincoln rerouted his troops, but they were delayed in reaching D.C., leaving that city open to attack. However, once the seat of power was secured, a furious Lincoln dispatched Union troops to seize Baltimore at night and occupy the Charm City for the remainder of the war.

Mayor Brown and Marshal Kane were soon arrested and thrown into jail without trial. Now it was John Wilkes Booth’s turn to be upset. Booth’s fellow actors remember his chilling words upon hearing of Kane’s arrest:

“I know George P. Kane well; he is my friend and the man who could drag him from the bosom of his family for no crime whatever, but a mere suspicion that he may commit one sometime deserves a dog’s death.”

Kane would serve over a year in prison. Upon his release, Kane headed to Canada, where he joined the Confederate Secret Service office in Montreal as “Colonel” Kane. During the course of the war, from neutral territory, Kane and his cohorts would orchestrate multiple attacks against the Union, such as fire bombings, train derailments, and even bank robberies. Kane was suspected of being the mastermind behind an aborted plot to free two thousand rebel prisoners from a Union military prison on Lake Eerie.

In late 1864, as the South’s position grew increasingly desperate, John Wilkes Booth traveled to Montreal with an audacious plan. Seeking out his friend Kane and the colonel’s Confederate Secret Service comrades, Booth proposed a scheme to kidnap President Lincoln and hold him for ransom in exchange for thousands of Confederate prisoners. The Montreal office seems to have approved the idea and has advanced Booth some seed money to organize the plot.

After months of recruiting his team, securing weapons, and preparing an escape route, Booth was ready to act. By March 1865, Booth and his conspirators were involved in at least two attempts to seize Lincoln as he traveled down Washington, D.C. roads in his carriage. These attempts appear to have been foiled by Lincoln’s changing plans. Meanwhile, Colonel Kane waited patiently in a remote, “out of the way” location in rebel-held Shenandoah Valley, Virginia.

Then, as Booth and his henchmen planned for yet another attempt at seizing Lincoln and holding him hostage, Union forces succeeded in surrounding Richmond. This forced Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet to flee via the rail line to Danville. The Davis party took the Confederate treasury and the gold of several Virginia banks for safekeeping.

Alerted to a sudden change in plans by a Confederate courier, Colonel Kane rode his horse south day and night in time to rendezvous with the retreating Jeff Davis train in Danville. A few days later, the Davis train departed Danville and headed south to Greensboro, North Carolina. Kane stayed behind. So did 39 very heavy barrels (9,000 pounds total) filled with Mexican silver coins, the profits from the sale of Confederate cotton.

Kane remained in Danville for nearly four years. The whereabouts of the Danville silver are unknown to this day.

Once back in Baltimore, Kane was quickly appointed to the municipal water board, known as the Jones Falls Commission. He likely secured this appointment with Charles Webb’s blessing. By 1873, Kane had left the Jones Falls Commission to run successfully for Sheriff of Baltimore. Webb employee Andrew J. Saulsbury, the homeowner with 5,000 gold coins buried in the basement, would replace Kane on the Jones Falls Commission.

In 1877, Kane ran for and won the office of Mayor of Baltimore. One of his first moves in office would be to appoint his longtime friend Charles Webb as tax collector for the city. The History of Baltimore City and County, Maryland, records that “Mr. Webb had always declined political office until the position of city collector was tendered him by Mayor Kane.” Apparently, the bond between Webb and Kane was so tight that Kane was the one individual to whom Webb could not say “no.”

But Kane died in office soon after. Booth, who had lived just four blocks from the treasure site, was already long dead. Saulsbury, only 46, died suddenly at his Eden Street home with his wife knowing nothing of the 5,000 gold coins buried in their basement. Captain Mattison succumbed soon after. One after one, the wealthy conspirators grew old and passed away… and the coins remained undisturbed, hidden with faint hopes for the day “the South would rise again.”

At a Freemason memorial service for Grand Master Charles Webb, his Masonic brothers recited a poem in his memory — a poem written by Albert Pike, the most powerful Freemason of his generation and the long-suspected head of the secretive Knights of the Golden Circle.

Time went on, and fortunes in coins were forgotten.

With the early 1900s death of Thomas Armstrong, the man likely responsible for the stash of coins found on-site at The Fountain Hotel in 1870, no one is left who was originally involved with the burial of the coins in the cellar at the treasure house on South Eden. The banking panic of 1907 came and went. The Titanic sinks in the North Atlantic. World War One devastates Europe. Prohibition is declared in the U.S. The Roaring Twenties ushers in an age of excess and rampant stock market speculation. Baltimore’s native son, George Herman “Babe” Ruth, revolutionizes the game of baseball by launching 60 home runs in a season. The Crash of ’29 heralds the beginning of the Great Depression. Proclaiming that we have “nothing to fear but fear itself,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt unveiled his plans for a New Deal to help the country out of its malaise.

In a declining inner-city neighborhood not far from the sometimes rough-and-tumble Depression-era Baltimore docks, two bored adolescent boys decide to go exploring in a dark corner of the basement of a crumbling tenement house. They are armed with an axe and a corn knife, but it is sufficient to uncover one of the greatest found treasures in American history. Knights’ Gold is their amazing story:

© Jack Myers, for Legends of America, updated May 2024.

About the Author: Jack Myers is the author of several books, including Row House Days, Row House Blues, and The Delco Files, as well as his book Knights’ Gold. He was born and raised in Philadelphia and has worked as a teacher, newspaper reporter, newspaper editor, pizza shop proprietor, and technical writer.

Also See: