Said to have been the fiercest Apache next to Geronimo, as well as a notorious outlaw of the late 19th century, was the Apache Kid.

Born in the 1860s on the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona, the “Kid” was most likely the White Mountain Apache. Named Haskay-bay-nay-natyl, “the tall man destined to come to a mysterious end,” the pronunciation was too much for the citizens of Globe, who called him “Kid.” Learning English at an early age, he worked at odd jobs in Globe and was soon befriended by the famous scout, Al Sieber.

At that time, early settlers of the Southwest faced numerous raiding bands of Apache, and General George Crook had come up with the idea to use Apache to fight other Apache. Enlisting Apache Indians from San Carlos and other reservations, the enlisted scouts could locate the trails that the hunted Apache traveled.

In 1881, the Kid enlisted in the Indian Scouts and was so good at the job that he was promoted to sergeant in July 1882. The following year he accompanied General George Crook on the expedition of the Sierra Madre.

The Geronimo Campaign of 1885-1886 found the Kid in Mexico early in 1885 with Sieber, and when the Chief of Scouts was recalled in the fall, Kid rode with him back to San Carlos. He re-enlisted with Lieutenant Crawford’s call for one hundred scouts for Mexican duty and went south in late 1885. In the Mexican town of Huasabas, on the Bavispe River, the Kid nearly lost his life in a drunken riot in which he had been a participant. The judge fined him twenty dollars rather than see the Apache Kid shot by a Mexican firing squad, and the Army sent him back to San Carlos.

In May 1887, the Apache Kid was left in charge of the Indian Scouts and guardhouse at San Carlos when Captain Pierce and Al Sieber, an anglo scout, were both gone on business. Though the brewing of tiswin, a beverage made of fermented fruit or corn, was illegal on the reservation, the Indian Scouts decided to have a party with the white officers gone. As the liquor flowed freely, a man named Gon-Zizzie killed the Apache Kid’s father, Togo-de-Chuz. Kid’s friends, in turn, killed Gon-Zizzie. However, the killing of Gon-Zizzie was not enough for the Apache Kid, who then went to the home of Gon-Zizzie’s brother, Rip, and killed him.

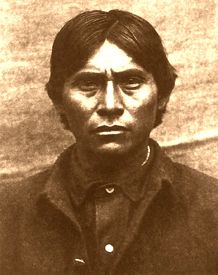

Apache Kid (middle) with two other Indian Scouts.

When the Apache Kid and the four other scouts returned to San Carlos on June 1, 1887, Captain Pierce and Al Sieber were there ahead of him. Captain Pierce ordered the scouts to disarm themselves, and the Kid was the first to comply. As Pierce ordered them to the guardhouse to be locked up, a shot was fired from the crowd who had gathered to watch the display of events. In no time, the shots became widespread, and Al Seiber was hit in the ankle, which ended up crippling him for life. During the melee that followed, the Apache Kid and several other Apache fled. Though it was never determined who fired that shot that struck Sieber, it was for sure not the Kid nor the other four scouts ordered to the guardhouse as they had all been disarmed.

The Army, reacting swiftly, soon sent two troops of the Fourth Cavalry to find the Apache Kid and the others who had escaped. For two weeks, the cavalry followed the fugitives along the banks of the San Carlos River, when finally, with the aid of more Indian Scouts, they located the Kid and his band in the Rincon Mountains.

The soldiers seized the Apache horses and equipment while the Indians fled by foot into the rocky canyons. In negotiations with the soldiers, Kid relayed a message to General Miles stating that he and his band would surrender if the Army would recall the cavalry. When Miles complied, the Apache Kid and seven members of his band surrendered on June 25.

The Kid and four others were court-martialed, found guilty of mutiny and desertion, and sentenced to death by firing squad. However, General Miles was upset over the verdict and ordered the court to reconsider the sentence. When the court reconvened on August 3, they were re-sentenced to life in prison. Miles

was still not satisfied and reduced the sentence to ten years. Beginning their sentence in the San Carlos guardhouse, they were later sent to Alcatraz.

However, their conviction was soon overturned on October 13, 1888, due to prejudice among the officers of the court-martial trial, and the Indians were returned to San Carlos as free men. Causing outrage among the area’s citizens, a new warrant was issued in October 1889 in Gila County for the re-arrest of the freed Apache for assault to commit murder in the wounding of Al Sieber.

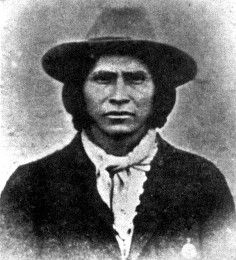

Apache Kid Wanted Poster

On October 25, 1889, four Apache, including the Apache Kid, were found guilty and sentenced to seven years in the Territorial Prison at Yuma. While being transported to the prison, the Apache Kid, along with several others, escaped. During the fighting during the escape, the three guards, Glenn Reynolds, Eugene Middleton, and W. A. Holmes were overpowered. Glen Reynolds was killed, Middleton was wounded, and Holmes died of a heart attack. Middleton later recovered, saying the Kid had prevented another Apache from “finishing” him by bashing his head with a rock.

The Kid and the others fled, their tracks obliterated by a snowstorm. It would be the last “official” sighting of Apache Kid, though unconfirmed reports of his whereabouts would continue to filter in for years.

Over the next few years, the Apache Kid was accused of various crimes and said to have led a small band of renegade Apache followers, raiding ranches and freight lines throughout New Mexico, Arizona, and Northern Mexico as he hid out in the Mexican Sierra Madre Mountains. Others insist that he became a lone wolf who was despised by his people and was feared by the Anglo settlers. Some accounts have the Apache Kid kidnapping an Apache woman until he tired of her, then killing her, before kidnapping yet another. Reportedly, the Kid preyed on lone ranchers, cowboys, and prospectors, killing them for their food, guns, and horses. Before long, the Arizona Territorial Legislature placed a price of $5,000 on his head, dead or alive, but no one ever claimed the reward.

It is impossible to determine how many of the crimes he is blamed for that he committed.

During an 1890 shootout between Sonoran Rurales (a branch of the Army) and Apache, a slain warrior was found to have Reynolds’ pistol and watch, but he was too old to have been the Kid. After 1894, reports of his crimes came to an end. Some sources claimed he died at this time, while others argue that he crossed into Mexico and retired to his mountain hideout.

Apache Kid

In 1899, Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky, head of the Rurales, reported him alive and living with other Apache in the Sierra Madre. In the interim, there were several unconfirmed reports of his death – by gunshot or by tuberculosis. However, southern Arizona ranchers continued to report Apache stock raids into the 1920s.

There are so many different variations of the crimes committed by the Apache Kid, all with the purpose of exacting revenge for the treacherous way in which the Apache scouts had been treated by the Army, that even historians cannot agree on precisely what he was responsible for, nor when he died. Seemingly, his namesake, “the tall man destined to come to a mysterious end,” was a prophecy.

Though the questions are many regarding the death of the Apache Kid, a gravesite memorial can be found high in the San Mateo Mountains of the Cibola National Forest in New Mexico. Here is yet another place that the Apache Kid was said to have been killed after having been hunted down by local ranchers angered by his relentless raids. Reportedly, to mark the site of the Kid’s undoing, the vengeful posse blazed a tree, the hacked remains of which you can see to this day. The grave is one mile northwest of Apache Kid Peak at Cyclone Saddle.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2024.

Also See:

Geronimo – The Last Apache Holdout

Apache – The Fiercest Warriors in the Southwest