Furnace Creek Ranch entry in Death Valley National Park, California. Photo by Kathy Alexander, 2015.

The industrial phase of Death Valley history began with the discovery of borax by Aaron and Rose Winters and the subsequent purchase of their claims by William T. Coleman in the early 1880s. After establishing a location for the Harmony Borax Works about 1½ miles north of the mouth of Furnace Creek, Coleman next addressed the need for a supply point to provide essential provisions for his mules and workmen at this plant and at his Amargosa Borax Works.

A logical place for this operation was the spot near the mouth of Furnace Creek Wash that had been homesteaded in the 1870s by a man named Bellerin Teck. The ranch consisted of a large adobe house with a wide northern veranda and was first referred to as “Greenland” and occasionally as “Coleman.” The Pacific Coast Borax Company gave it its present name sometime after 1889.

Furnace Creek Ranch in its early days, Death Valley, California

Coleman sent to Italy for gardeners to supervise the agricultural development of the site. At great expense, the soil was scientifically fertilized, and various types of trees were planted. In addition, a half-acre pond was constructed, and water from the Furnace Range was diverted from Travertine Springs to the ranch via a stone-lined ditch to irrigate 30-40 acres of alfalfa and trees.

With about 40 men actively employed at the borax works, and considering its vital function as a terminus station for the 20-mule teams, where wagons could be repaired while men and animals enjoyed the luxury of a few days’ leisure after their exhausting round-trip haul to the railhead, the ranch became an important center of operations. Under the guardianship of James Dayton and by constant irrigation, livestock flourished in this barren desert, as did the growth of melons, vegetables, alfalfa, figs, and cottonwoods. The presence of water, shade trees, and grass in the area led to temperatures that usually ranged from eight to ten degrees cooler than elsewhere in the valley, and by 1885 the farmstead was rich in alfalfa and hay, while cattle, hogs, and sheep were supplying fresh meat for the tables of the Harmony Borax workers.

The promotional possibilities offered by this cool oasis greatly appealed to Coleman, who at one point envisioned eventually establishing a resort here. However, those dreams were rapidly deflated by the downward spiraling of his economic fortunes, which ultimately forced him to mortgage all of his holdings to Francis M. “Borax” Smith and eventually lose them all in 1890. Smith’s stewardship began with closing both the Harmony and Amargosa Borax Works, as his business efforts concentrated solely on his new mine at Borate. Jimmy Dayton, however, remained as a watchman for the borax plant and caretaker of the ranch farm.

Initially, Smith displayed none of Coleman’s enthusiasm for creating a resort or other vacation spot at the ranch and ran it solely as a commercial venture. However, as the shade trees grew and the fruit trees prospered, the spot turned into a friendly oasis frequently visited by prospectors and other wanderers in need of rest and refreshment. The buildings were improved and new tropical trees planted, but otherwise, few changes were made.

Dayton served as caretaker and foreman of the ranch for about 15 years until his death in 1899. By the early years of the next century, a man named Oscar Denton had taken over his duties, and with the help of local Indians, was continuing to raise alfalfa and figs. The ranch continued to be a resting place for prospectors where they could lounge beneath the trees, bathe in the ditches, and find companionship while awaiting supplies to be sent from Death Valley Junction.

There were, however, a few drawbacks to life at this veritable Shangri-la, not the least of which was the intense summer heat. The ranch’s location 178 feet below sea level on the floor of Death Valley makes it the lowest place in the western hemisphere where vegetation thrives. The constantly warm environment required that young palms and other tropical plants be set in the shade of houses or older trees to ensure their survival. In summer, activity on the ranch ceased during the daylight hours, the enervating atmosphere making all but the most perfunctory tasks impossible.

Mostly the time was spent lounging in hammocks hung across the wide veranda. A five-foot fan revolved by water power generated a breeze on the ranch house porch. The pervasive stillness of the day, however, was in contrast to the evening bustle, when ranch chores were performed, and the more pleasant aspects of life–eating, drinking, and playing cards–were indulged in with gusto.

Death Valley Railroad on display at Borax Museum at Furnace Creek Ranch in Death Valley. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

In the fall of 1907, rumors circulated that Francis Smith was thinking about developing the Furnace Creek Ranch as a winter resort and was even contemplating extending a branch line of the Death Valley Railroad to provide access to both his borax deposits along Furnace Creek Wash and the ranch. By the next year, rumors of the plan also included establishing a health resort for persons suffering from pulmonary disorders and related afflictions. However, in the end, these visions did not occur.

In 1922, the U.S. Weather Bureau established a substation at the ranch, and at about the same time, poultry raising was experimented with, date growing was added, and the ranch became involved in the business of production of dressed meat. After much experimentation in the growing of dates, this would become the principal product of the ranch.

In 1930, when the hotel at Ryan closed, the borax company felt that some accommodations should be offered in the valley that would be less expensive and of a more relaxed sort than were found at Furnace Creek Inn. Because of the ranch’s abundance of water and its level building site, it seemed the logical place for such an undertaking. Eighteen tent houses formed the construction camp at the Furnace Creek Inn were moved down to the site. To these, were added several workers’ bungalows from the just-completed Boulder (later Hoover) Dam, which were moved to the site and remodeled for tourist use. A 16 x 36-foot boarding house and cabins from the abandoned Gerstley Mine near Shoshone were also used to bolster the accommodations.

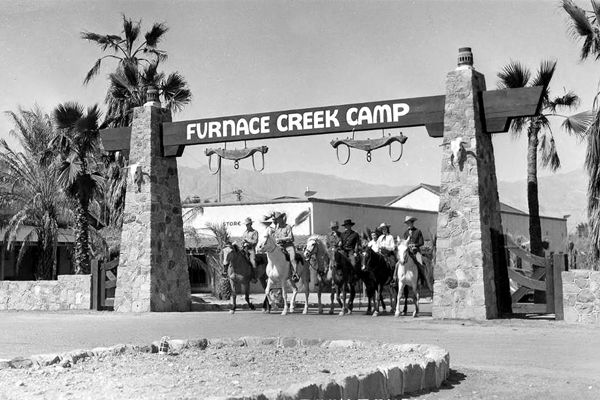

Vintage Furnace Creek Camp, Death Valley, California

The Ranch hotel first opened its doors for business in 1933, and for two years, the wives of the Ranch foreman and mechanic operated the hotel, which underwent a continual program of enlargement and expansion over the next ten years. The balance of the cabins were built in the period from 1935 to 1939, with the lobby, store, and dining room constructed in 1934-35. In 1936 a building originally erected for drying dates was used as a schoolhouse for 15-20 children. The recreation hall was built in 1936, the kitchen was enlarged in 1952, and the office and swimming pool in 1952.

The advent of World War II not only postponed a $150,000 building program for the Ranch planned by the Pacific Coast Borax Company, which included a projected new lobby, dining room, coffee shop, and kitchen, plus new parking facilities and fifty new cabins but, also resulted in a shutdown of services. By the time this took place, however, the Ranch had accommodations for 350 people, plus a nine-hole all-grass golf course added in 1930. After the three-year hiatus, the Ranch, Inn, and Amargosa Hotel reopened in 1945 and were run for ten years by Charles Scholl. Then, in 1955, they were all leased to the Fred Harvey organization, which decided to concentrate its operations within the valley, resulting in the sale of the Amargosa Hotel in 1959. The newest units at the Ranch, located alongside the golf course, were completed in 1975, and other recreational facilities, such as tennis courts, were completed in 1977.

Equipment at the Borax Museum at Furnace Creek Ranch in Death Valley National Park, California. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

Today, the property is owned by the Xanterra Corporation and is part of the Oasis At Death Valley Resort. The complex provides guests with an 18-hole golf course, three restaurants, a saloon, swimming pool, tennis courts, horseback riding, tours, and an airstrip. There are 224 guest units. The highlight of the ranch is the Borax Museum, which was opened in the 1950s. The old borax office building from Twenty-Mule-Team Canyon was moved to the Ranch around 1954, and its interior was filled with exhibits on mining, Indian populations of the valley, and railroad history. Outside are antique vehicles, wagons, a stagecoach, the Death Valley Railroad Engine No. 2, and more. The Four Diamond Inn (aka Furnace Creek Inn) is also part of the resort.

The ranch is located on Highway 190 at Furnace Creek, California.

More information: The Ranch At Death Valley

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated December 2021.

Source: Greene, Linda W., and Latschar, John A; Death Valley Historic Resource Study; National Park Service, 1979.

See our Death Valley Photo Print Gallery HERE