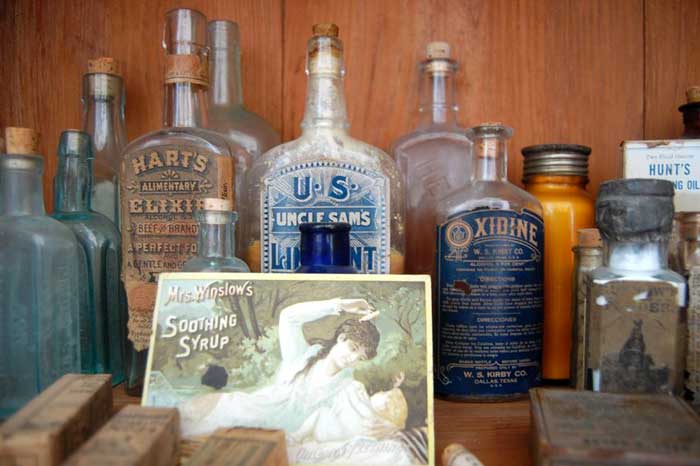

Medicine cabinet at LARCs Arcadian Village, Lafayette Louisiana.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “patent medicine” became very popular for various aches, ailments, and diseases. Often sold by traveling salespeople in what became known as “medicine shows,” these many decoctions had colorful names and even more colorful claims. Despite the name “patent medicine,” these elixirs and tonics were rarely patented, except a few, including Castoria, and instead were often trademarked. Chemical patents did not come into use in the United States until 1925.

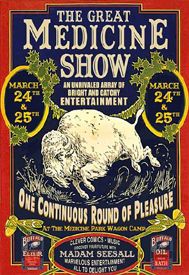

The Great Medicine Show.

Also called “proprietary medicines,” these elixirs and tonics originated in England. They were manufactured under grants, or “patents of royal favor,” to those who provided medicine to the Royal Family, hence the name. In the 18th century, these medicines began to be exported to America and were sold by various merchants, including grocers, goldsmiths, drugstores, and even postmasters.

Flourishing in the United States from the start, by the middle of the 19th century, the manufacture of patent medicines was a major industry in America.

Produced by large companies as well as small family operations, remedies were available for almost any ailment, including venereal diseases, tuberculosis, infant colic, digestive problems, “female complaints,” and even cancer. These remedies were openly sold to the public in retail stores, by individual salesmen, and in what would develop into the traveling medicine show.

Promoting patent medicines was one of the first significant products heavily displayed in the early advertising industry. During this time, numerous advertising and sales techniques were pioneered by patent medicine promoters. Often, these advertisements would promote exotic ingredients, even when their actual effects came from more common drugs. “Branding” of products became popular to distinguish one medicine from its numerous competitors. Though most patent medicines were sold at high prices, they were generally made from cheap ingredients. Pharmacists who knew the composition of these remedies would often manufacture similar products and sell them at lower prices. To counteract this, branded medicine advertisements urged the public to accept no substitutes.

One popular group of patent medicines – liniments and ointments – often promoted themselves as containing snake oil, which was thought to have been a cure-all at the time. This would eventually lead to using the term “snake oil salesman,” a lasting synonym for a charlatan.

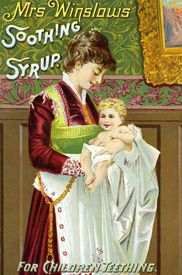

Winslow’s Soothing Syrup.

These medicines were very popular, even though many of them were laced with ample doses of alcohol, morphine, opium, or cocaine, and were advertised for babies and children, sometimes ending in tragic results. With no regulation on their often questionable ingredients, concerns began to grow about these medicines. Their effectiveness was also questionable, and ingredients were usually kept secret, leading to their being referred to as “quack” medicines. Just a few instances of high alcohol levels included Lydia Pinkham’s Women’s Tonic, which contained 19% alcohol; Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root was 12 %; and Hostetter’s Bitters, an amazing 32%.

From the beginning, many doctors and medical societies were critical of patent medicines, arguing that they did not cure illnesses, discouraged the sick from seeking legitimate treatments, and caused alcohol and drug dependency. More fierce resistance came from the temperance movement of the late 19th century, which loudly protested the use of alcohol in medicines.

Resisting these criticisms, manufacturers established “The Proprietary Association” in 1881. The trade group of medicine producers, aided by the press, which had grown dependent on the money received from remedy advertising, fought bitterly against any regulation. However, in the end, their resistance would be overcome by the demand for safety. In 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act was enacted, which required manufacturers to list their ingredients on packaging labels and restricted misleading advertising. Later, in 1938, another law required that manufacturers test their products for safety before marketing them, and in 1962, tests for effectiveness were required.

Cotton bale medicine, 1888.

Though many patent medicines were only ruses, a few legitimate ones delivered the promised results, such as Listerine, which was developed in 1879, Bayer Aspirin in 1899, Milk of Magnesia in 1880, Ex-Lax in 1905, and Richardson’s Croup and Pneumonia Cure Salve in the 1890s, which is now known as Vick’s VapoRub.

Medicine Shows:

Another publicity method taken to sell these many patent medicines was the ever-popular “Medicine Show,” which sometimes resembled a small traveling circus, complete with vaudeville-style entertainment, “Muscle Man” acts, magic tricks, and Native American and Wild West themes. These shows originated in the performances by traveling charlatans in 14th century Europe when circuses and theaters were banned, and performers had only the marketplace or patrons for support. Later, patent medicine vendors would set up booths at local fairs in Colonial America. As early as 1773, laws were being passed against their excesses. By the late 19th century, Medicine Shows flourished in the United States, especially in the Midwest and the rural South.

The Medicine Man, often called “Professor” or sometimes “Doctor,” was generally neither; but rather, was a talented showman and storyteller. With the “Professor” at the center, these medicine shows were often structured around entertainers who could be expected to draw a crowd of potential customers who would listen to and then purchase the “miracle elixirs” offered by the “doctor.”

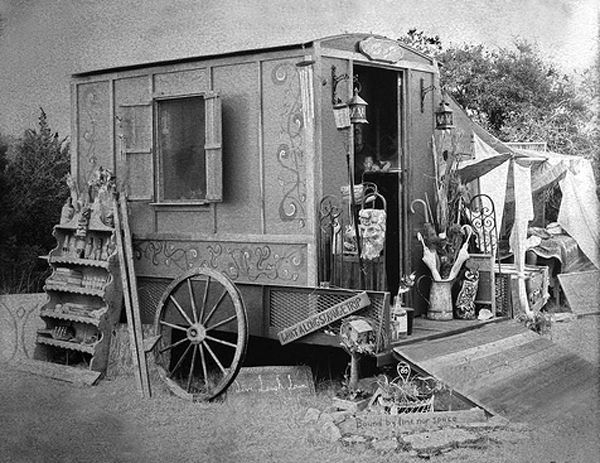

Medicine Show Wagon.

Much ado was made before these events, such as posters and banners displaying the time and place of the show and tickets of admission. Sometimes, these “shows” were so large that halls or hotels were booked for the troupes of entertainers, who might be enacted several times throughout the day and evening. However, most often, they were held right on the street, hopefully attracting every passerby. These remedies and elixirs were often manufactured and bottled in the same wagon where the show traveled.

Between entertainment acts, the “Professor” would lecture the crowd about his miraculous elixir, mixing grandiose claims with interesting anecdotes and stories. Often, the audience was encouraged to join in with singing entertainers. “Muscle man” acts were especially popular in these shows to impress the crowd with the strength and vigor he obtained from a particular potion. During these presentations, the “Professor” frequently employed shills who would step forward from the crowd and offer “unsolicited” testimonials about the medicine’s benefits for sale. Other “plants” within the audience who had an obvious affliction, such as a limp, would shuffle forward and challenge the “Medicine Man” and his claims. Amazingly, after the “Professor” gave the individual a teaspoon of his “magical elixir,” the rube was suddenly cured. Though many, no doubt, knew that these antics were a bit unbelievable, they wanted to believe that this particular cure worked.

Sig Molitamo, Cuban Wonder Fire Eater, Kickapoo Medicine Company.

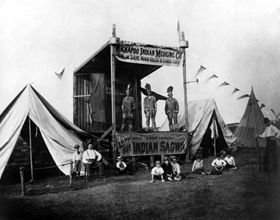

In addition to the “Mom and Pop” operations that wound their way through small towns and rural areas with their “Medicine Wagons,” several large manufacturers presented “Medicine Shows” in a significant manner. The most well-known of these was the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company. Headquartered in New Haven, Connecticut, far away from the Kickapoo tribe, who primarily lived on a reservation in Oklahoma at the time. Founded by non-Native Americans John E. “Doc” Healy and Charles H. “Texas Charley” Bigelow, the pair called their large headquarters building “The Principal Wigwam.” This building served as both a factory and living quarters for employees and housing offices for the two owners. In 1881, Doc Healy, who owned a brokerage house in Boston, got the idea of promoting medical elixirs using Indian names and, the following year, took on his partner, Charles Bigelow. Healy was in charge of hiring the performers – both Indians and white performers- who included jugglers, acrobats, dancers, musicians, fire-eaters, and more. Texas Charley managed the medicine side of the business, as well as the “Doctors” or “Professors” who gave “Medical Lectures.”

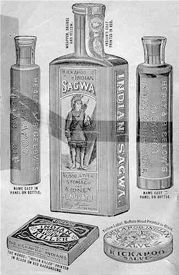

Kickapoo Indian Medicine.

These two partners would send as many as 25 shows at a time across the country. During the shows, all the entertainers were in flamboyant costumes, the Native Americans covered in feathers and colored beads and often carrying crude weapons. The “Professors” often wore tuxedo-style jackets, high silk hats, and clothing with gold studded buttons, glitter, silk, fringe, and more.

According to the advertisements and the “professors,” the medicines sold were “compounded according to secret ancient Kickapoo Indian tribal formulas.” In fact, ingredients often included herbs used by Native Americans, including bloodroot, feverwort, poke, slippery elm, oak bark, and other natural products. Selling for 50 cents to a dollar per bottle, these medicines are guaranteed to cure all manner of ailments.

Company shows featured Native American-style entertainment, including horseback riding, Pow Wows, dances, and invocations to various spirits in darkened tents. One popular product was Kickapoo Indian Sagwa, which was touted as a Blood, Liver, and Stomach Regulator. This was said to have been based on a Native American Herbal Remedy, but, in actuality, it was a mixture of alcohol, stale beer, and a strong laxative such as aloe. The Kickapoo Indian Sagwa would inspire Al Capp’s “Kickapoo Joy Juice,” featured in the comic strip “Li’l Abner.” The company also sold several other patent medicines, such as Kickapoo Indian Oil, Kickapoo Cough Cure, and Kickapoo Worm Remedy, claiming their basis in Indian herbal medicine. The benefit of claiming traditional native origins was that disproving was nearly impossible.

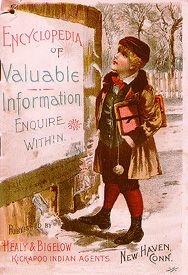

Encyclopedia of Valuable Information, 32-page pamphlet, Kickapoo Indian Medicine Co., 1894.

One of the most popular performers in the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show was a man named Dr. John Johnson. Though he looked, acted, and had the knowledge of an Indian Medicine Man, he was not of Indian heritage. However, for more than 20 years, he believed that he was.

In actuality, he was kidnapped from Saco, Maine’s Factory Island, by Mi’kmaq Indians from Nova Scotia in 1834 when he was just five years old. Brought up to believe he was a member of the tribe, he learned traditional Indian medical practices and was regarded among the Indians as a Medicine Man. Later, he was reunited with his family and studied with several American doctors. He was also regarded as a physician by the white people. Dr. Johnson would appear in many of the company’s shows.

Along with the company’s many shows and performers, they also published various books and pamphlets to promote their products independently. These publications, which covered Indian life and lore, included the Encyclopedia of Valuable Information, a 32-page pamphlet published in 1894; Life and Scenes among the Kickapoo Indians, a 176-page illustrated book published in 1900; and the Kickapoo Doctor, a 32-page pamphlet published in 1890.

Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show continued into the 1920s when its white owners sold out for almost a half-million dollars. However, other medicine shows continued for the next two decades.

The last of these traveling shows was the Hadacol Caravan, which marketed a tonic called “Hadacol,” known for its alleged curative powers and its high alcohol content. Primarily making appearances in the South, the show was known for its notable music acts and Hollywood celebrities. The Caravan suddenly stopped in 1951 when the Hadacol enterprise fell apart in a scandal.

Today, many medicines from the patent medicine era still survive,, including Anacin/Anadin, Bayer Aspirin, Bromo-SeltzerCarter’s Little Pills, Doan’s Pills, Fletcher’s Castoria, Geritol, and others. A number of products that once made medicinal claims and were once marketed as patent medicines are still on the market, though their ingredients have changed. These include 7-Up, Angostura Bitters, Coca-Cola, and Tonic Water.

©Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show.

Also See:

Herbal Teas (Legends’ General Store)

Herbs, Plants & Healing Properties

See Sources.