By John A. Hill and Jasper Ewing Brady in 1898

I am just back from a visit to old scenes, old chums, and old memories of my interesting experience on the western fringe of Uncle Sam’s great, gray blanket—the plains.

If some of these fellows who know more about writing than about running engines would only go out there for a year and keep their eyes and ears and brains open and mouths shut, they could come home and write us some true stories that would make fiction grinders exceedingly weary.

The frontier attracts strong characters, men with a pioneer spirit, men who are willing to sacrifice something to gain an end, men with love, and men with hate. Bad men are there, some of them hunted from Eastern communities, perhaps, but you will find no fools and mighty few weak faces—there’s a character in every feature you look at.

Everyone is there for a purpose; to accomplish something; to get ahead in the world; to make a new start; perhaps to live down something, or to get out of the rut cut by ancestors; some may only want to drink, and shout, and shoot, but even these do it with a vim—they mean it.

Of the many men who ran engines at the front, with me in the old days, I recall few whose lives were purposeless; almost everyone had a life story.

If there’s anything that I enjoy, it’s sitting down to a pipe and a life story—told by the subject himself. How many have I listened to, out there, and every one of them worthy of the pen of a Kipling!

The frontier population is never all made up of men, and the women all have strong features, too—self-sacrifice, devotion, degradation, or something, is written on every face. There are no blanks in that lottery—there’s little material there for homes of the feeble-minded.

It isn’t strange, either, when you come to think of it; fools never go anywhere; they are just born and raised. If they move, it’s because they are “took”—you never heard of a pioneer fool.

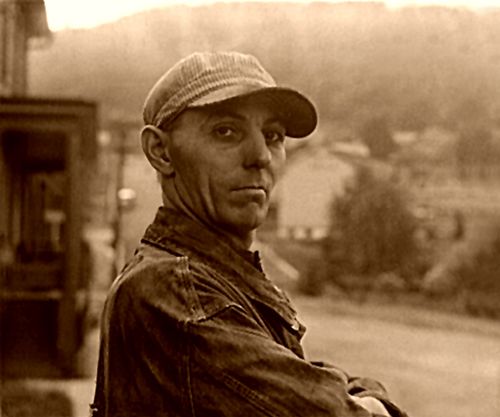

One of the strongest characters I ever knew was a runner out there by the name of Gunderson—Oscar Gunderson. He was of Swedish parentage, very light-complexioned, very large, and a splendid mechanic, as Swedes are apt to be when they try. Gunderson’s name was, I suppose, properly entered on the company’s time book, but it never was in the nomenclature of the road. With the railroaders’ gift for abbreviation and nickname, Gunderson soon came down to “Gun,” his size, head, hand, or heart furnished the prefix of “Big,” and “Big Gun” he remains today. “Big Gun” among his friends, but simple “Gun” to me. I think I called him “Gun” from the start.

Gun ran himself as he did his engine, exercised the same care of himself, and always talked engine about his own anatomy, clothes, food, and drink.

His hat was always referred to as his “dome-casing;” his Brotherhood pin was his “number-plate;” his coat was “the jacket;” his legs the “drivers;” his hands “the pins;” arms were “side-rods;” stomach “fire-box;” and his mouth “the pop.”

He invariably referred to a missing suspender button as a broken “spring-hanger;” to a limp as a “flat-wheel;” he “fired up” when eating; he “took water,” the same as the engine; and “oiled round,” when he tasted whisky.

Gun knew all the slang and shop-talk of the road and used it—was even accused of inventing much of it—but his engine talk was unique and inimitable.

We roomed together a whole winter, and often, after I had gone to bed, Gun would come in, and as he peeled off his clothes, he would deliver himself something as follows:

“Say, John, you don’t know who I met on the up trip? Well, sir, Dock Taggert. I was sailin’ along up the main line near Bob’s, and who should I see but Dock backed in on the sidin’—seemed kinder dilapidated, like he was runnin’ on one side. I jest slammed on the wind and went over and shook. Dock looks pretty tough, John—must have been out surfacing track, ain’t been wiped in Lord knows when, oiled a good deal, but nary a wipe, jacket rusted and streaked, tire double flanged, valves blowin’, packing down, don’t seem to steam, maybe’s had poor coal, or is all limed up. He’s got to go through the back shop ‘efore the old man’ll ever let him into the roundhouse. I set his packin’ out and put him in a stall at the Gray’s corral; hope he’ll brace up. Dock’s a mighty good workin’ scrap, if you could only get him to carryin’ his water right; if he’d come down to three gauges he’d be a dandy, but this tryin’ to run first section with a flutter in the stack all the time is no good—he must ‘a flagged in.”

Which, being translated into English, would carry the information that Gun had seen one of the old ex-engineers at Bob Slattery’s saloon, had stopped and greeted him. Dock looked as if he had tramped, had drank, was dirty, coat had holes, soles of his boots badly worn, wheezing, seemed hungry and lifeless, been eating poor food, and was in a general run-down condition. Gun had “set out his packing” by feeding him and put him in a bed at the Grand Central Hotel—nicknamed the “Grayback’s Corral.” Gun thought he would have to reform before the M. M. put him into active service. He was a good engineer but drank too much, and lastly, he was in so bad a condition he could not get himself into headquarters unless someone helped him by “flagging” for him.

Gun was a bachelor; he came to us from the Pacific side, and told me once that he first went west on account of a woman, but—begging Mr. Kipling’s pardon—that’s another story.

“I don’t think I’d care to double-crew my mill,” Gun would say when the conversation turned to matrimony. “I’ve been raised to keep your own engine and take care of it, and pull what you could. In double-heading, there’s always a row as to who ought to go ahead and enjoy the scenery or stay behind and eat cinders.”

I knew from the first that Gun had a story to tell if he’d only give it up, and I fear I often led up to it with the hope that he would tell it to me—but he never did.

My big friend sent a sum of money away every month, I supposed to some relative, until one day I picked up from the floor a folded paper dirty from having been carried long in Gun’s pocket, and found a receipt. It read:

“Mission, San Antonio, Jan. 1, 1878.

“Received of O. Gunderson, for Mabel Rogers, $40.00.

“Sister Theresa.”

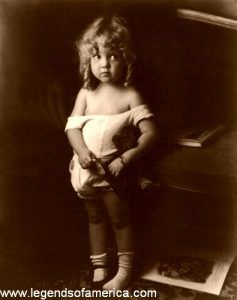

Ah, a little girl in the story! I thought it’s a sad story, then. There’s nothing so pure and beautiful and sweet and joyous as a little girl, yet when a little girl has a story, it’s almost always a sad story.

I gave Gun the paper; he thanked me, said he must look out better for those receipts, and added that he was educating a bit of a girl out on the coast.

“Yours, Gun?” I asked kindly.

“No, John; she ain’t; I’d give $5,000 if she was.”

He looked at me straight, with that clear, blue eye, and I knew he told me the truth.

“How old is she?” I asked.

“I don’t know; ’bout five or six.”

“Ever seen her?”

“No.”

“Where did you get her?”

“Ain’t had her.”

“Tell me about her?”

“She was willed to me, John, kinder put in extra, but I can’t tell you her story now, partly because I don’t know it all myself and partly because I won’t—I won’t even tell her.”

I did not again refer to Gun’s little girl; soon, other experiences and biographies crowded the story out of my mind.

One evening in the spring, I sat by the open window, enjoying the cool night breeze from off the mountains, when I heard Gun’s cheery voice on the porch below. He was lecturing his fireman, in his own, unique way.

“Well, Jim, if I ain’t ashamed of you! There ain’t no one but you; coming into general headquarters with a flutter in the stack, so full that you can’t whistle, air-pump a-squealing ‘count of water, smeared from stack to man-hole, headlight smoked and glimmery, don’t know your own rights, kind o’ runnin’ wildcat, without proper signals, imagining you’re the first section with a regardless order. You want to blow out, man, and trim up, get your packing set out and carry less juice. You’re worse than one of them slippin’, dancin’, three-legged, no-good Grants.”

“The next time I catch you at high tide, I’ll scrap you; that’s what I’ll do, fire you into the scrap pile. Why can’t you use some judgment in your runnin’? Why can’t you say, ‘Why, here’s the town of Whisky, I’m going to stop here and oil around,’ sail right into town, put the air on steady and fine, bring her right down to the proper gait, throw her into full release, so as to just stop right, shut off your squirt, drop a little oil on the worst points, ring your bell and sail on.

“But you, you come into town forty miles an hour, jam on the emergency and while the passengers pick ’emselves out of the ends of the cars, you go into the supply house and leave the injector on, and then, when you do move, you’re too full to go without opening your cylinder cocks and givin’ yourself dead away.

“Now, I’m goin’ to Californ’, next month, and if you get so as you can tell when you’ve got enough liquor without waiting for it to break your injectors, I’ll ask the old man to let you finger the plug on Old Baldy whilst I’m gone. But I’m damned if I don’t feel as if you was like that measly old 19—jest fit to be jacked up to saw wood with.”

While Gun was in California, I was taken home on a requisition from my wife, and Oscar Gunderson and his little girl became a memory—a page in a book that I had partly read and lost, but not entirely forgotten.

One day last summer I took the westbound express at Topeka, and spreading my grip, hat, coat and umbrella, out on the seats, so as to resemble an experienced English tourist, I fished up a Wheeling stogie and a book and went into the smoking-pen of the sleeper, which I had all to myself for half-an-hour.

The train stopped to give the thirsty tender a drink and a man came in to wash his hands. He had been riding on the engine.

After washing, he stepped to the door of the “smokery,” struck a match on the leg of his pants, held both hands around the end of his cigar while he lighted it, then waving the match to put it out, he threw it down and came in.

While he was absorbed in all this, I took a glance at him. Six-foot-four, if an inch; high cheek bones; yellow beard; clear, blue eyes; white skin, and a hand about the size of a Cincinnati ham. I knew that face despite twelve years of turkey-tracks about the eyes.

“Gunderson, old man, how are you?” I said, offering my fin.

“Well, John Alexander, how in the name of thunder did you get away out here on the main stem, without orders?”

“Inspection-car,” said I; “how did you get here?”

“Deadheading home; been out on special, a gilt-edged special, took her clean through to New York.”

“You did!” I exclaimed; “why, how was that?”

“Went up special to a weddin’, don’t you see? Went up to see a new compound start off—prettiest sight I ever saw—working smooth as grease; but I’m kind of dubious about repairs and general running. I’m anxious to see how the performance sheet looks at the end of the year, John.”

“Who’s been double-heading, Gun?”

“Why—why, my little girl, trimmest, neatest, slickest little mill you ever saw. Lord! but she was painted red and white and gold-leaf, three brass bands on her stack, solid nickel trimming, all the latest improvements, corrugated fire-box, high-pressure smoke consumer and sand-jet—jest made a purpose for specials, and pay-car. But if she ain’t got herself coupled onto a long-fire-boxed ten-wheeler, with a big lap and a Joy gear, you can put me down for a clinker. Yes, sir; the baby is a heart-breaker on dress-parade, and the ten-wheeler is a whale on business, and if they don’t jump the track, you watch out for some express speed that will make the canals sick, see if they don’t.”

Without giving me time to say a word, he was off again.

“You ought to seen ’em start out, nary a slip, cutting off square as a die, small one ahead speaking her little piece chipper and fast on account of her smaller wheels, and the ten-wheeler barking bass, steady as a clock, with a hundred-and-enough on the gauge, a full throttle, and half a pipe of sand. You couldn’t tell to save you whether the little one was pulling the big one or the big one shoving the little—never saw a relief train start out in such shape in my life.”

Gunderson was evidently enthusiastic over the marriage of his little girl. We talked over old times and the changes, and followed each other up to date with a great deal of mutual enjoyment, until the porter demanded the “smokery” for his bunk.

As we started for bed, Gun laid his hand on my shoulder and said:

“John, a good many years ago, you asked me to tell you the story of my little girl. I refused then for her sake. I’ll tell you in the morning.”

After a hearty breakfast and a good cigar, Gunderson squared himself for the story. He shut his eyes for a few minutes, as if to recall something, and then, speaking as if to himself, he said:

“Well, sir, there wasn’t a simmer anywhere, dampers all shut; you wouldn’t’a suspected they was up to the popping point, but the minute they got their orders, and the con. put up his hand, so, up went—”

“Say,” I interrupted, “I thought I was to have the story. I believe you told me about the wedding, last night. The young couple started out well.”

“Oh, yes, old man, I forgot, the story; well, get on the next pit here,” motioning to a seat next to him, “and I’ll give you the history of an old, hook-motion, name of Oscar Gunderson, and a trim, Class “G” made of solid silver, from pilot to draft-gear.

“You think I’m a Swede; well, I ain’t, I don’t know what I am, but I guess I come nearer to being a Chinaman than anything else. My father was a sea-captain, and my mother found me on the China sea—but they were both Swedes just the same. I had two sisters older than myself, and in order to better our chances, father moved to New York when I was less than five years old.

“He soon secured work as captain on a steamer in the Cuban trade, and died at sea, when I was ten.

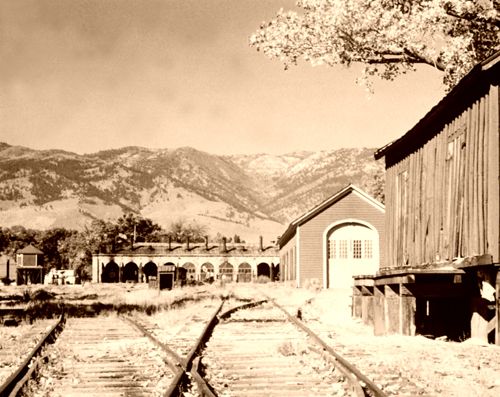

“I had a bent for machinery and tried the old machine shops of the Central road but soon found myself firing.

“I went to California, shortly after the war, on account of a woman—mostly my fault.

“Well, after running around there for some years, I struck a job on the Virginia & Truckee in ’73.

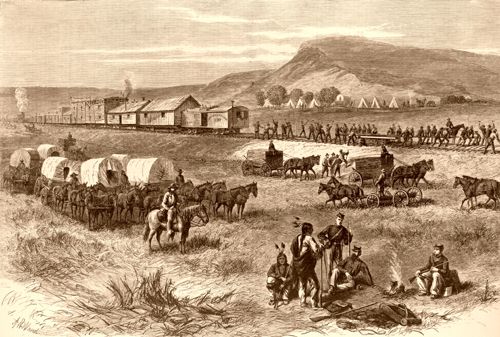

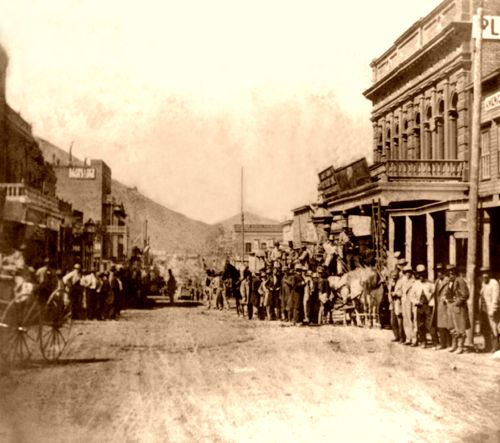

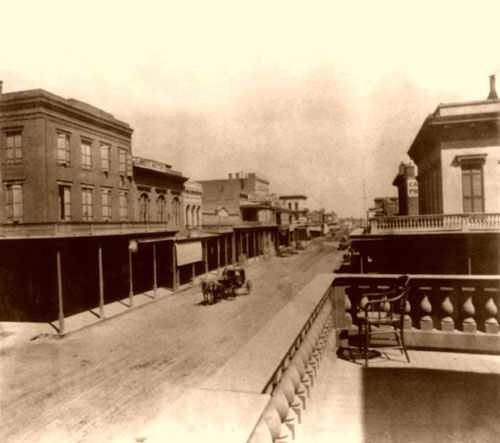

“Virginia City and Carson and all the Nevada towns were doing a fall-rush business, turning every wheel they had, with three crews to a mill. Why, if you’d go down street in any one of them towns at night and see the crowds around the gamblers and molls, you’d think hell was a-coming forty-mile an hour and that it wan’t more than a car-length away.

“Well, one morning, I came into Virginia [City] about breakfast time, and with the rest of the crew, went up to the old California Chop-house for breakfast. This same chop-house was a building about good-enough for a stable, these days; but it had a reputation then for steaks. All the gamblers ate there; and it’s a safe rule to eat where the gamblers do, in a frontier town, if you want the best there is, regardless of price.

“It was early for the regular trade, and we had the dining room mostly to ourselves, for a few minutes, then there were four women folks came in and sat down at a table bearing a card: ‘Reserved for Ladies.’

“Three of them were dressed loud, had signs out whereby anyone could tell that they wouldn’t be received into no Four Hundred; but one of them was a nice-looking, modestly-dressed woman, had on half-mourning, if I remember.

“She had one of them sweet, strong faces, John, like the nun when I had my arm broke and was scalded—her sweet mouth kept mumblin’ prayers, but her fingers held an artery shut that was trying its damndest to pump Gun Gunderson’s old heart dry—strong character, you bet.

“Well, that woman sat facing our table and kept looking at me; I couldn’t see her without turning, but I knew she was looking. John, did you ever notice that you could feel the presence of some people; you knew they were near you without seeing them? Well, when that happens, don’t forget to give that fellow due credit; for whoever it is he or she has the strongest mind—the dominant one.

“I had to look around at that woman. I shall never forget how she looked; her hand was on the side of her face; her great, brown, tender eyes were staring right at me—she was reading my very soul. I let her read.

“I had been jacking up a gilly of a gafter who had referred to his mother as “the old woman,” and I didn’t let the four females disturb me. I meant to hold up a looking glass for that young whelp to look into. I hate a man that don’t love his mother.

“Why,” says I, “you miserable example of Divine carelessness, do you know what that ‘old woman’ mother has done for you, you drivelin’ idiot, a-thankin’ God that you’re alive and forgetting the very mother that bore you; if you could see the tears that she has shed, if you could count the sleepless nights that she has put in, the heartaches, the pain, the privation that she has humbly, silently, even thankfully borne that you might simply live, you’d squander your last cent and your last breath to make her life a joy, from this day until her light goes out. A man that don’t respect his mother is lost to all decency; a man who will hear her name belittled is a Judas, and a man who will call his mother ‘old woman’ is a no-good, low-down, misbehaven whelp. Why, damn it, I’d fight a buzz-saw, if it called my mother ‘old woman’—and she’s been dead a long time; gone to that special, exalted, gilt-edged and glorious heaven for mothers. No one but mothers have a right to expect to go to a heaven, and the only question that’ll be asked is, ‘Have you been a mother?’

“Well, sir, I had forgot about the women, but they clapped their hands and I looked around, and there were tears in the eyes of that one woman.

“She got up; came to our table and laid a card by my plate, and said, ‘I beg your pardon; but won’t you call on me? Please do.’

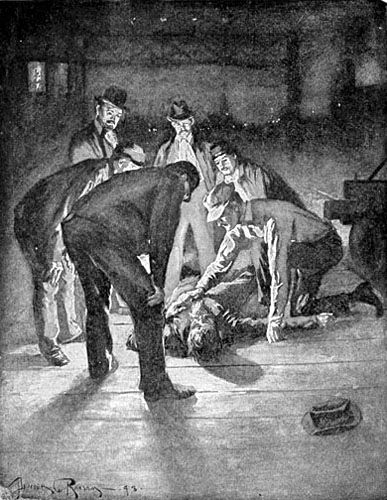

“He was the first man I ever killed.” Illustration from the book, Danger Signals by John A. Hill and Jasper Ewing Brady.

“I was completely knocked out, but told her I would, and she went out alone; the others finished their breakfast.

“She had no sooner gone than Cy Nash, my conductor, commenced to giggle—’Made a mash on the flyest woman in town,’ he tittered; ‘ain’t a blood in town but what would give his head for your boots, old man; that’s Mabel Verne—owns the Odeon dance hall, and the Tontine, in Carson.’

“I glanced at the card, and it did read, ‘Mabel Verne, 21 Flood avenue.’

“Well, Flood avenue is no slouch of a street, the best folks live there,” I answered.

“‘Yes, that’s her private residence, and if you go there and are let in, you’d be the first man ever seen around there. She’s a curious critter, never rides or drives, or shows herself off at all; but you bet she sees that the rest of the stock show off. She’s in it for money, I tell you.’

“I don’t know why, but it made me kind of heart-sick to think of the hell that woman must be in, for I knew by her looks that she had a heart and a brain, and that neither of them was in the Odeon or the Tontine dance-houses.

“I thought the matter over,—and didn’t go to see her. The next trip, she sent a carriage for me.

“She met me at the door, and took my hat, and as I dropped into an easy chair, I opened the ball to the effect that ‘this here was a strange proceeding for a lady.’

“‘Yes,’ said she, sitting down square in front of me; ‘it is; I felt as if I had found a true man, when I first saw you, and I have asked you here to tell you a story, my story, and ask your help and advice. I am so earnest, so anxious to do thoroughly what I have undertaken, that I fear to overdo it; I need counsel, restraint; I can trust you. Won’t you help me?”

“‘If I can; what is it that you want me to do, madam?’

“‘First of all, keep a secret, and next, protect or help protect, an innocent child.’

“‘Suppose I help the child, and you don’t tell me the secret?’

“‘No, it concerns the child, sir; she is my child; I want her to grow up without knowing what her mother has done, or how she has lived and suffered; you wouldn’t tell her that, would you?’

“‘No, certainly not!’

“‘Nor anyone else?’

“‘No.’

“‘You would judge her alone, forgetting her mother?’

“‘Yes.’

“‘Then I will tell you the story.’

“She got up and changed the window blinds so that the light shone on my face; I guess she wanted to study the effect of her words.

” ‘I was born at Sacramento,’ she began; ‘my father was a well-to-do mechanic, and I his only child; I grew up pretty fair-looking, and my parents spent about all they could make to complete my education, especially in music, of which I was fond. When I was eighteen years old, I fell in love with a young man, the son of one of the rich merchants of San Francisco, where we had removed. Like many another foolish girl, I trusted too implicitly and believed too easily and soon found myself in a humiliating position, but trusted the honor of my lover to stand by me.

“‘When I explained matters to him he seemed pleased, said he could fix that easy enough; we would get married at once and claim a secret marriage for some months past.

“‘He arranged that I should meet him the next evening and go to an old priest in an obscure parish and be married.

“‘I stood long hours on a corner, half dead with fear, that night, for a lover that never came. He’s dead now, got run over in Oakland yard, that very night, as he was running away from me, and as I waited and shivered under the stars and the fire of my own conscience.’

“‘Did he stand on one track, to get out of the way of another train, and get struck?’ I asked.

“‘Yes,’ looking at me close.

“‘Did he have on a false moustache, and a good deal of money and securities in a satchel, and everybody think at first he was a burglar?’

“‘Yes; but how did you know that?’

“‘Because, I killed him.’

“‘You?’

“‘Yes; I ran an engine over him, couldn’t make him hear or see me. He was the first man I ever killed; strange he should be this particular man.’

“‘It’s fate,’ said the woman, rocking slowly back and forth, ‘it’s fate, but it seems as though I like you better now that you were my avenger. That accident drove revenge out of my heart, caused me to let him be forgotten, and to live for my child. I have lived for her. I live to-day for her and I will continue to live for her.’

“‘My disgrace killed my mother and ruined my father. I swore I would be an honest woman, and I sought employment to earn a living for my babe and myself, but every avenue was closed to me. I washed and scrubbed while I was able to teach music splendidly, but I could get no pupils. I made shirts for a pittance and daily refused, to me, fortunes for dishonor. I have gone hungry and almost naked to pay for my baby’s board, but I was hunted down at last.

“‘One day, after many rebuffs in seeking employment, I went to the home of a sister of my child’s father, and took the baby, told her who I was and asked her to help me to a chance to work. The good woman scarcely looked at me or the child; she said that had it not been for such as I, poor Charles would have been alive; his blood was on my head; I ought to ask God to wash my blood-stained hands.

“‘I went away from that house with my mind made up what to do. I would put my child in honest hands, and chain myself to the stake to suffer everlasting damnation for her sweet sake.

“‘She is in the Mission San Antonio now, between three and four, a perfect little princess, she looks like me, and grows, oh, so lovely! If you could see her, you’d love her.

“‘I can’t go to see her any more; she is old enough to remember. The last time I was there, she demanded a papa!

“‘I am making a great deal of money. Many of the rich men, whose Puritan wives and daughters refused me honest work, are squandering lots of their wealth in my houses. I am saving money, too; and propose, as soon as I can get a neat fortune together to go away to the ends of the earth, and have my little girl with me. I will raise her to know herself and to know mankind.’

“‘And what do you want me to do, madam?’

“‘I want you to be that child’s guardian; the honest man through whom she will reach the outside of San Antonio and the world. Who will go between her and me until a happier time.’

“‘I am only a rough engineer; the child will be raised to consider herself well off, perhaps rich.’

“‘Adopt her. I will stay in the background; make her expenditures and her education what you like. I will trust you.’

“‘I can’t do that.’

“‘You are single; your life is hard; I have money enough for us all. Let us go to the Sandwich islands, anywhere, and commence life anew. The little one will know no other father, and all inquiry will be stopped.’

“‘I couldn’t think of it, my dear madam; it’s too easy; it’s like pulling jerkwater passenger—I like through freight.’

“Well, John, to make a long story short, the interview ended about here, and several more got to about the same place. There were a thousand things I could not help but admire in that woman, and I liked her better the more I knew her. But it wan’t love; it was a sort of an admiration for her love of the child, and the nerve she displayed in its behalf. But I shrank from becoming her husband or companion, although I think she loved me, in the end, better than she ever did anybody.

“However, I finally agreed to look after the little one, in case anything happened to the mother, and commenced then to send the money for her board and tuition, and the mother dropped out of all connection with the child or those having her in charge.

“The mother made her pile and got out of the business, and at my suggestion, went down near Los Angeles and bought a nice country place to start respectable before she took the little one home. She left money in Carson, subject to my check, for the little girl, and things slid along for a year or so all smooth enough.

“I was out on a snow-bucking expedition one time the next winter, sleeping in cars, shanties or on the engine, and I soon found myself all bunged up with the worst dose of rheumatiz’ you ever see. I had to get down to a lower altitude, and made for Sacramento in the spring. I paid the Mission a year in advance, and with less than a hundred dollars of my own, struck out, hoping to dodge the twists that were in my bones.

“A hundred blind gaskets don’t go far when you’re sick, and the first thing I knew, I was dead broke; couldn’t pay my board, couldn’t buy medicine, couldn’t walk—nothing but think and suffer. I finally had to go to a hospital. Not one of the old gang ever came to see me. Old Gun was a dandy, when he was making—and spending—a couple hundred a month; the rest of the time, he was supposed to be dead.

“I might have died in the hospital if fate hadn’t decreed to send me relief. It suddenly dawned upon me that I was getting far better treatment than usual, had a special nurse, the best of food, flowers, etc., all labeled ‘From the Boys.'”

“I found out, after I was well enough to take a sun bath on the porch, that a woman had sent all my luxuries and that her purse had been opened for my relief. I knew who it was at once and was anxious to get well and at work, so as not to live on one who was only too glad to do everything for me.

“A six months’ wrastle with the twisters leaves a fellow stiff-jointed and oldish, and lying in bed takes the strength out of him. I took the notion to get out and go to work, one day, and walked down to the shops—I was carried back, chuck full of ’em again.

“The doctor said I must go to Ojo Caliente, away down south, if I was to get well. John, if the Santa Fé road had ‘a been for sale for a cent then, I couldn’t ‘a bought a spike.

“At about the height of my ill-luck, I got a letter from Mabel Verne—she had another name, but that don’t matter—and she asked me again to come to her; to have a home, and care and devotion. It wasn’t a love-sick letter, but it was one of them strong, tender, fetching letters. It was unselfish, it asked very little of me, and offered a good deal.

“I thought over it all night, and decided at last to go. What better was I than this woman? Surely she was better educated, better bred. She had made one mistake, I had made many. She had no friends on earth; I didn’t seem to have any, either. I hadn’t had a letter from either of my married sisters for six or eight years, then. We could trust one another, and have an object in life in the education of the child. I’d be no worse off than I was, anyway.

“The next morning I felt better. I got ready to leave, bid all my fellow flat-wheels good-by; and had a gig ordered to take me to the train—the doctor had given me two-hundred dollars a short time before—’from a lady friend.’

“As I sat waiting for the hack, they brought me a letter from home—a big one, with a picture in it. It was from my youngest sister, and the picture was of her ten-year boy, named for me—such a happy, sunny little Swede face you never see. ‘He always talks of Uncle Oscar as a great and good man,’ wrote Carrie, ‘and says every day that he’s going to do just like you. He will do nothing that we tell him Uncle Oscar would not like, and anything that he would. If you are as good as he thinks you are, you are sure of heaven.’

“And I was even then going off to live with a woman who made a fortune out of Virginia City dance houses. I had a sort of a remorseful chill, and before I really knew just where I was, I had got to Arizona, and from there to the Santa Fé where you knew me.

“I wrote my benefactress an honest letter, and told her why I had not come, and in a short time sent her the money she had put up for me, but it was returned again, and I sent it to the mission for my little girl.

“Well, while I was with you there, I got a fare-thee-well letter, saying that when I got that Mabel Verne would be no more—same as dead—and that she had deposited forty thousand dollars in the Phoenix Bank for your little girl—yours, mind ye—and asked me to adopt her legally and tell her that her mother was dead.

“John, I ain’t heard of that woman from then until now. I thought she had gotten tired of waiting on me and got married, but I believe she is dead.

“I went to California and adopted the baby—a daisy too—and I’ve honestly tried to be a father to her.

“I got to making money in outside speculations and had plenty, so I let her money accumulate at the Phoenix and paid her way myself.

“About four years ago, I left the road for good; bought me a nice place just outside of Oakland and settled down to take a little comfort.

“Mabel, my daughter Mabel, for she called me papa, went to Germany nearly three years ago in charge of her music teacher, Sister Florence, to finish herself off. Ah, John, you ort to see her claw ivory! Before she went, she called me into the mission parlor one day and almost got me into a snap; she wanted me to tell her all about her parents right then and asked me if there wasn’t some mystery about her birth and the way she happened to be left in the mission all her life, her mother disappearing, and my adoption of her.”

“What did you tell her, Gun?” I asked.

“Why, lied to her, of course, as any honorable man would have done. I told her that her father was an engineer and a friend of mine and that he was killed in an accident before she was born—that was all plausible enough.

“Then I told her that her mother was in poor health and had died just before I had adopted her and had left a will, giving her to me, and besides had left forty thousand dollars in the bank for her when she married or became of age.

“Well, John, cutting down short, she met a fellow over there, a New Yorker, that just seemed to think she was made a-purpose for him, and about a year ago he wrote and asked me for my daughter—just think of it! His petition was seconded by the baby herself, and recommended by Sister Florence.

“They came home six months ago, and the baby got ready for dress-parade; and I went down to New York and seen ’em off; but here’s where old Fate gets in his work again. That rascal of an O. B. Sanderson—I didn’t notice the name before—was my own nephew, the very young cuss whose picture kept me from marryin’ the baby’s mother! I never tumbled till I ran across his mother, she was my sister Carrie.

“John, I don’t care a continental cuss how good he was, the baby was good enough for him—too good—I just said nothing—and watched the signals. You ort to a seen me a-givin’ the bride away! Then, when it was all over, and I was childless, I give my little girl a check for forty-seven thousand and a fraction; kissed her, and lit out for home—and here I am.

“But I ain’t satisfied now, and just as quick as I get back, I’m a-going running again; then, when I’ve got so old I can’t see more’n a car length, I’m going to ask for a steam-pump to run. I’m a-going to die railroading.”

“Have you ever made any inquiries about the mother, Gun?” I asked.

“No; not much; it’s so long now, it ain’t no use; I guess that her light’s gone out.”

“What would you do, if she was to turn up?”

“Well, I don’t know; I guess I’d keep still and see what she done.”

“Suppose, Gun, that she showed up now, loved you more than ever for what you have done, and renewed her old proposal? You know it’s leap year.”

“Well, old man, if an angel flew down out of the sky and give me a second-hand pair of wings just rebuilt, and ordered me to put ’em on and follow her, I guess I wouldn’t refuse to go out. Time was, though, when I’d a-held out for new, gold-mounted ones, or nothing; but that won’t come, John; but you just ort to a been to the consolidation; it was just simply—well, pulling the president’s special would be just like hauling a gravel-train to it!”

The train stopped suddenly here, and “Gun” said he was going ahead to get acquainted with the water-boiler, and I took out my notebook and jotted down a few points.

After the train got into motion again, I was reading over my notes when, without looking, I thought Gunderson had come back, and I moved along in the seat to give him room, but a black dress sat down beside me.

We had been sitting with our backs to a curtain between the first berth and a stateroom. The lady came from the stateroom.

“Pardon me, sir,” she said, “I want to finish that story. I have heard it all; I am Sister Florence, music teacher to Mr. Gunderson’s daughter; he does not know that I am on this train.

“Mr. Gunderson did not tell you that the Phoenix bank failed some months ago and that the fortune of his adopted child was lost. He never told her, and she does not know it today—”

“He said he paid her the full amount—” I interrupted.

“Very true. He did; but he paid it out of his own pocket. Sold his farm, put up all his securities, and borrowed seven hundred dollars to make the sum complete. That is the reason he is going to run an engine again. He does not know that I am aware of this, so don’t mention it to him.”

“Gun is a man,” said I; “a great, big-hearted, true man.”

“He is a nobleman!” said the nun, arising and going back into the stateroom.

Half an hour later, Gunderson came back, took a seat beside me, and commenced to talk.

“Say, John, that’s the hardest-riding old pelter I ever see, about three inches of slack between engine and tank, pounding like a stamp-mill and—” looking over his shoulder and then at me, “John, I could a swore there was someone standing right there, I felt ’em.

“It seems to me they ort to keep up their engines here in pretty good shape. They’ve got bad water and so much boiler work that they have to have new flues before the machinery gets worn much. But, Lord, they don’t seem—” he looked over his shoulder again, quickly, then settled in his seat to resume when a pair of hands covered Gun’s eyes—the nun’s hands.

“Guess who it is, Gun,” said I; and noticed that he was very pale.

“It’s Mabel,” said he, putting up his hands and taking both of hers; “no one but her ever made me feel like that.”

John A. Hill, Jasper Ewing Brady, 1898. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Author & Notes: This tale is adapted from a chapter of a book written by John A. Hill and Jasper Ewing Brady, entitled Danger Signals, first published in 1898 and again in 1902 by Chicago Jamieson-Higgins Co. The tale is not 100% verbatim, as minor grammatical errors and spelling have been corrected.

Also See: