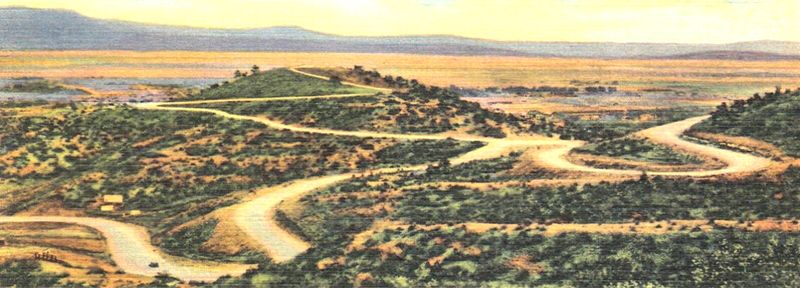

At the border of present-day New Mexico and Colorado, Raton Pass was one of the most important yet treacherous segments of the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail. The pass cut through the snow-capped Sangre de Cristo Mountains, allowing wagons access to the vast western territory.

When Spain controlled the southwestern United States, the Spanish officially banned international trade of all kinds. After Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, the Mexicans lifted the ban and opened the area to both commercial and cultural exchange. The Santa Fe Trail, which spanned 1,200 miles from Franklin, Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico passing through deserts, mountains, and forests, became the primary means of transportation to and from the area.

Shorter routes were eventually developed, but Raton Pass, which crossed safer terrain, remained in use. The pass played a critical role in General Stephen Watts Kearny’s conquest of Santa Fe and the eventual American annexation of New Mexico in 1846.

As the first major passage west through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the Raton Pass National Historic Landmark celebrates the development of American trade, cultural interaction, and westward expansion.

Sangre de Cristo Range, courtesy Wikipedia.

When Mexico opened its borders to trade with the United States in 1821, a great commercial, military, and emigrant trail was born. However, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains loomed huge and daunting between the western edge of the United States in Missouri and the bustling Mexican center of commerce, Santa Fe. Early explorers, trappers, and American Indian peoples had previously discovered various paths through the treacherous mountains, but before 1821, no covered wagons had made the journey.

In June 1821, William Becknell, a horse and mule trader, traveled west from Franklin, Missouri, with a wagon and four companions. History has written for years that Becknell would be the first of many to travel via wagon through the narrow, torturous Raton Pass. However, that portion of his journey has been called into question after the discovery of the diary of Pedro Ignacio Gallego in 1993. Mexican Captain Gallego and his 400 men met Becknell on his first journey to Santa Fe. His writings, along with Becknell’s journal describing the landscape, show more evidence that he and his men probably misidentified the Canadian River and instead crossed another river or stream. Researchers now say evidence points to a location between the Arkansas River and Puertocito Piedra Lumbre in Kearny Gap, south of present-day Las Vegas, New Mexico.

Santa Fe Trail near “The Caches” in Ford County, Kansas

Soon, however, a new branch of the Santa Fe Trail developed. The so-called “Cimarron Route” was not only 100 miles shorter but cut across the relatively flat grasslands and deserts of present-day Kansas and Oklahoma instead of through the mountains. Although the openness of the Cimarron Route led to frequent raids from American Indian tribes and provided far less water, the dangers of the shorter path were still preferable to travel. Between the 1820s and early 1840s, most of the wagon traffic along the Santa Fe Trail opted to take the Cimarron Route.

In 1846, the pass again played a significant historical role. Tensions were running high between the United States and Mexico over land disputes in Texas, which included what is now the State of New Mexico. Both countries lay claim to the land, and Mexico disputed the decision of the United States to annex Texas in 1845. President James Polk declared war on Mexico in 1846 and sent American forces into the territory. General Stephen Watts Kearny set out with his famed 1,600-man “Army of the West” along the Santa Fe Trail.

Although the Mountain Branch and the Raton Pass were dangerous, Kearny chose to head west through the mountains rather than take the Cimarron Route. The steep, narrow Raton Pass afforded better protection from invading forces and ample water supply, unlike the dry desert along much of the Cimarron Route. Before Kearny and his men arrived, a team of workers set out along the trail to make passage more accessible, including clearing rocks and debris from the notorious Raton Pass. Despite their efforts, Kearny’s journey was still fraught with difficulty. Many wagons were destroyed, and supplies had to be left behind.

Weakened, the men emerged from the Raton Pass and expected to meet resistance from Mexican forces that the provincial governor Manuel Armijo sent. They instead found the valley abandoned. Kearny’s takeover of Santa Fe thus was swift. Without a struggle, the United States laid claim to the territory.

The Mountain Branch was again mostly abandoned after its use by Kearny’s army because traders and travelers still preferred the shorter, easier route. However, the Raton Pass saw use once again with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1860. The vulnerability of the Cimarron Branch was recognized as concerns heightened around Confederate raids. The Santa Fe Trail saw heavy use as a Union Army supply route west, and the narrow, protected Raton Pass was easy to guard. The pass continued to serve Union troops through 1865.

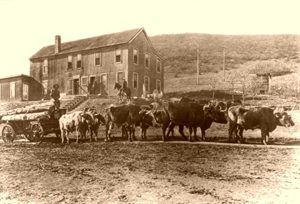

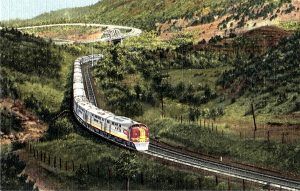

Raton Pass became part of a toll road for several years that entrepreneur Richens L. Wootton built and managed at the war’s end. Beginning in 1866, the most treacherous part of the Santa Fe Trail was heavily altered by grading, blasting, bridge building, and clearing. The formerly difficult Raton Pass was made passable in all seasons for horses, wagons, and stagecoaches alike. While Wootton’s toll road was highly profitable, the advancing western railroad system soon overtook it. By the late 1870s, train traffic replaced Raton Pass and the Santa Fe Trail, which led to the abandonment of the epic trade route by 1880.

The railroad that once scaled the pass via a series of switchbacks has since been re-routed beneath the mountain through a tunnel. Much of the rest of the rail line still follows the old route of the Santa Fe Trail through Raton Pass and along Raton Creek. Though much of the trail has been wiped out by new highway construction, distinct original segments remain.

The 7,881-foot summit is accessible via I-25. A New Mexico Welcome Center allows visitors to step out of their vehicles to see the incredible view, once only afforded to the Santa Fe Trail travelers. An informative historical marker for Raton Pass interprets the landmark both at the center and on the Colorado side of the State border. Public access to the land, however, is restricted, as the wilderness is privately owned. The nearby city of Raton, New Mexico, celebrates its trail heritage, and the Raton Museum, located at 108 2nd Street, interprets the area’s past for curious visitors.

Today, Raton Pass is a National Historic Landmark located along the Santa Fe National Historic Trail, a unit of the National Park Service. The pass is located five miles north of Raton, New Mexico.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See: