From Chronicles of America Series, 1919

New Jersey, called Scheyichbi by the Indians, had a history somewhat different from that of other English colonies in America. It was a good-sized dominion surrounded by water, almost an island domain, secluded and independent. It was the only one of the colonies which stood naturally separate and apart. The others were bounded almost entirely by artificial or imaginary lines.

It offered an opportunity; one might have supposed, for some dissatisfied religious sect of the 17th century to secure a sanctuary and keep off all intruders. But at first, no one of the various denominations seems to have fancied it or chanced upon it. The Puritans disembarked upon the bleak shores of New England, well suited to the sternness of their religion. How different American history might have been if they had established themselves in Jersey. Could they, under those milder skies, have developed witchcraft, set up blue laws, and indulged in the killing of Quakers? After a time, they learned about the Jerseys and cast thrifty eyes upon them.

Their seafaring habits and the pursuit of whales led them along the coast and into Delaware Bay. The Puritans of New Haven tried to settle the southern part of Jersey on the Delaware River near Salem. They thought that if they could start a branch colony in Jersey, it might become more populous and powerful than the New Haven settlement, and in that case, they intended to move their seat of government to the new colony. But their wise estimate of its value came too late. The Dutch and the Swedes occupied the Delaware River then and drove them out. Puritans, however, entered northern Jersey. While they were not numerous enough to make it a thoroughly Puritan community, they primarily affected its thought and laws, and their influence still survives.

The difficulty with Jersey was that its seacoast was a monotonous line of breakers with dangerous shoal inlets, few harbors, and vast mosquito-infested salt marshes and sandy thickets. In the interior, it was mostly a level, heavily forested, sandy, swampy country in its southern portions and rough and mountainous in the northern portions. Even the entrance by Delaware Bay was so tricky because of its shoals that it was the last part of the coast to be explored. The Delaware region and Jersey were, in fact, a sort of middle ground far less easily accessible by the sea than the regions to the north in New England and the south in Virginia.

There were only two places easy to settle in the Jerseys. One was the open meadows and marshes by Newark Bay near the mouth of the Hudson River and along the Hackensack River, where people slowly extended themselves to the seashore at Sandy Hook and then southward along the ocean beach. This was East Jersey. The other easily occupied region, which became West Jersey, stretched along the shore of the lower Delaware River from the modern Trenton to Salem, where the settlers gradually worked their way into the interior. A rough wilderness in its southern portion lay between these two divisions, full of swamps, thickets, and pine barrens. So rugged was the country that the native Indians lived in, for the most part, only in the two open regions already described.

The natural geographical, geological, and even social division of New Jersey is made by drawing a line from Trenton to the mouth of the Hudson River. North of that line, the successive terraces of the Piedmont and mountainous region form part of the original North American continent. South of that line, the more or less sandy level region was once a shoal beneath the ocean; afterward, a series of islands, then one island with an expansive sound behind it, passing along the division line to the mouth of the Hudson River. Southern Jersey was, in short, an island with a sound behind it, much like the present Long Island. The shoal and island had been formed in the distant geologic past by the erosion and washings from the lofty Pennsylvania mountains, which were now worn down to mere stumps.

The Delaware River flowed into this sound at Trenton. Gradually, the Hudson River end of the sound filled up as far as Trenton, but the tide from the ocean still ran up the remains of the Old Sound as far as Trenton. The Delaware River should still be considered ending at Trenton, for the rest of its course to the ocean is still part of Old Pennsauken Sound.

The Jerseys originated as a colony in 1664. In 1675, West Jersey passed into the control of the Quakers. In 1680, East Jersey came partially under Quaker influence. In August 1664, King Charles II seized New York, New Jersey, and all the Dutch possessions in America, having previously, in March, granted them to his brother, the Duke of York. The Duke almost immediately gave to Lord Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, members of the Privy Council, the land between the Delaware River and the ocean, and bounded on the north by a line drawn from latitude 41° on the Hudson River to latitude 41° 40′ on the Delaware River.

This region was to be called New Jersey. Berkeley and Carteret divided the province between them. In 1676, an exact division was attempted, creating the somewhat unnatural sections known as East Jersey and West Jersey. The first idea seems to have been to divide by a line running from Barnegat on the seashore to the mouth of Pennsauken Creek on the Delaware River just above Camden. This, however, would have made a North Jersey and a South Jersey, with the latter а much smaller than the former. Several lines seem to have been surveyed at different times in an attempt to make an exact equal division, which was no easy engineering task. As private land titles and boundaries were, in some places, dependent on the location of the division line, there was much controversy and litigation, which lasted into our own time. Without going into details, it is sufficient to say that the acceptable division line began on the seashore at Little Egg Harbor at the lower end of Barnegat Bay and crossed diagonally or northwesterly to the northern part of the Delaware River just above the Water Gap. It is known as the Old Province line, and it can be traced on any State map by prolonging, in both directions, the northeastern boundary of Burlington County.

West Jersey, which became decidedly Quaker, did not remain long in possession of Lord Berkeley. He was growing old, and, disappointed in his hopes of seeing it settled, he sold it in 1673 for 1000 pounds to John Fenwick and Edward Byllinge, who were Quakers. That this purchase was made to afford a refuge in America for Quakers then much imprisoned and persecuted in England does not very distinctly appear. But such a purpose, in addition to profit for the proprietors, may well have been in the purchasers’ minds.

George Fox, the Quaker leader, had just returned from a missionary journey in America, in the course of which he had traveled through New Jersey, going from New York to Maryland. Some years previously, in England, about 1659, he had made inquiries about a suitable place for Quaker settlement and was told of the region north of Maryland, which became Pennsylvania. But how could a persecuted sect obtain such a region from the British Crown and the Government that was persecuting them? It would require powerful influence at Court; nothing could then be done about it, and Pennsylvania had to wait until William Penn became a man with enough influence in 1681 to win it from the Crown. But here was West Jersey, no longer owned directly by the Crown and bought cheaply by two Quakers, which was an unexpected opportunity. Quakers soon went to it, which was the first Quaker colonial experiment.

Byllinge and Fenwick soon quarreled over their respective interests in the ownership of West Jersey, and to prevent a lawsuit so objectionable to Quakers, the decision was left to William Penn. A rising young Quaker about 30 years old, dreaming of ideal colonies in America. Penn awarded Fenwick a one-tenth interest and 400 pounds. Byllinge soon became insolvent and turned over his nine-tenths interest to his creditors, appointing Penn and two other Quakers, Gawen Lawrie, a merchant of London, and Nicholas Lucas, a maltster of Hertford, to hold it in trust for them. Gawen Lawrie became deputy governor of East Jersey afterward. Lucas was one of those thoroughgoing Quakers just released from eight years in prison for his religion.

Fenwick also, in the end, fell into debt and, after selling over 100,000 acres to about 50 purchasers, leased what remained of his interest for a thousand years to John Edridge, a tanner, and Edmund Warner, a poulterer, as security for money borrowed from them. They conveyed this lease and their claims to Penn, Lawrie, and Lucas, who thus became the owners, as trustees, of pretty much all of West Jersey.

This was William Penn’s first practical experience in American affairs. He and his fellow trustees, with the consent of Fenwick, divided the West Jersey ownership into 100 shares. The 90 shares belonging to Byllinge were sold to settlers or creditors who would take them in exchange for his debts. The settlement of West Jersey thus became the distribution of an insolvent Quaker’s estate among his creditor fellow religionists. Although no longer in possession of a land title, Fenwick, in 1675, went out with some Quaker settlers to Delaware Bay. There, they founded the modern town of Salem, which means peace, giving it that name because of the fair and peaceful aspect of the wilderness on the day they arrived.

They bought the land from the Indians, as the Swedes and Dutch often did. But they had no charter or provision for an organized government. When Fenwick attempted to exercise political authority at Salem, he was seized and imprisoned by Governor Andros of New York for the Duke of York on the ground that, although the Duke had given Jersey to certain individual proprietors, the political control of it remained in the Duke’s deputy governor. Andros, who had levied a five percent tax on all goods passing up the Delaware River, now established commissioners at Salem to collect the duties. This action brought up the whole question of Andros’ authority. The trustee proprietors of West Jersey appealed to the Duke of York, who was suspiciously indifferent to the matter. Finally, they referred it for a decision to a prominent lawyer, Sir William Jones, before whom the Quaker proprietors of West Jersey made a most excellent argument. They showed the illegality, injustice, and wrong of depriving the Jerseys of vested political rights and forcing them from the freeman’s right to make their laws to a state of mere dependence on the arbitrary will of one man.

Then, with much boldness, they declared that “To exact such an unterminated tax from English planters, and to continue it after so many repeated complaints, will be the greatest evidence of a design to introduce if the Crown should ever devolve upon the Duke, an unlimited government in old England.” These were prophetic words that the Duke, in a few years, tried his best to fulfill. But Sir William Jones decided against him; he acquiesced, confirmed the political rights of West Jersey by a separate grant, and withdrew any authority Andros claimed over East Jersey. The trouble, however, did not end there. Domineering attempts from New York long afflicted both the Jerseys.

Penn and his fellow trustees then prepared a constitution, or Concessions and Agreements, as they called it, for West Jersey, the first Quaker political constitution embodying their advanced ideas, establishing religious liberty, universal suffrage, and voting by ballot, and abolishing imprisonment for debt. It foreshadowed some of the ideas subsequently included in the Pennsylvania Constitution. All these experiences were an excellent school for William Penn. He learned the importance of starting a colony and having a carefully and maturely considered system of government. In his preparations some years afterward for establishing Pennsylvania, he avoided much of the bungling of the West Jersey enterprise. A better-organized attempt was made to establish a foothold in West Jersey farther up the river than Fenwick’s colony at Salem. In 1677, the ship Kent took out some 230 rather well-to-do Quakers, about as fine a company of broadbrims, it is said, as ever entered the Delaware River. Some were from Yorkshire and London, largely creditors of Byllinge, who were taking land to satisfy their debts. They all went up the river to Raccoon Creek on the Jersey side, about 15 miles below the present site of Philadelphia, and lived at first among the Swedes, who had been in that part of Jersey for some years and who took care of the new arrivals in their barns and sheds. These Quaker immigrants, however, soon began to take care of themselves, and the weather during the winter proved mild; they explored farther up the river in a small boat. They bought from the Indians the land along the river shore from Oldman’s Creek all the way up to Trenton. They made their first settlements on the river about 18 miles above the site of Philadelphia, at a place they at first called New Beverly, then Bridlington, and finally Burlington.

They may have chosen this spot partly because there had been an old Dutch settlement of a few families there. It had long been a crossing of the Delaware River for the few persons who passed by land from New York or New England to Maryland and Virginia. One of the Dutchmen, Peter Yegon, kept a ferry and a house for entertaining travelers. George Fox, who crossed there in 1671, described the place as having been plundered by the Indians and deserted. He and his party swam their horses across the river and got some of the Indians to help them with canoes.

Other Quaker immigrants followed, going to Salem and Burlington, and a stretch of some 50 miles of the river shore became strongly Quaker. Not many American towns are now to be found with more of the old-time picturesqueness and more relics of the past than Salem and Burlington.

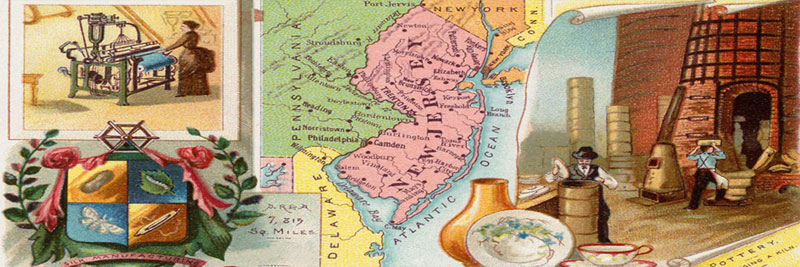

Settlements were also started on the river opposite the site afterward occupied by Philadelphia, at Newton on the creek still called by that name, and another a little above on Cooper’s Creek, known as Cooper’s Ferry until 1794. Since then, it became the flourishing town of Camden, full of shipbuilding and manufacturing, but for long after the American Revolution, it was merely a small village on the Jersey shore opposite Philadelphia, sometimes used as a hunting ground and a place of resort for duelers and dancing parties from Philadelphia.

The Newton settlers were Quakers of the English middle class, weavers, tanners, carpenters, bricklayers, chandlers, blacksmiths, coopers, bakers, haberdashers, hatters, and linen drapers; most of them possessed property in England and bringing good supplies with them. Like all the rest of the New Jersey settlers, they were in no sense adventurers, gold seekers, cavaliers, or desperadoes. They were well-to-do middle-class English tradespeople who would never have thought of leaving England if they had not lost faith in the stability of civil and religious liberty and the security of their property under the Stuart Kings. With them came servants, as they were called; that is, persons of no property who agreed to work for a specific time in payment for their passage to escape from England. All escaped from England before their estates melted away in fines and confiscations, or their health or lives ended in the damp, foul air of the crowded prisons.

Many of those who came had been in jail and decided they would not risk imprisonment a second time. Indeed, the proportion of West Jersey immigrants who had been in prison for holding or attending Quaker meetings or refusing to pay tithes for the support of the established church was large. For example, while in jail for his religion, William Bates, a carpenter, made arrangements with his friends to escape to West Jersey as soon as he should be released. His descendants are now scattered over the United States. Robert Turner, a man of means who settled finally in Philadelphia but also owned much land near Newton in West Jersey, had been imprisoned in England in 1660, again in 1662, again in 1665, and some of his property had been taken, again imprisoned in 1669 and more property taken; and many others had the same experience. Details such as these make us realize the situation from which the Quakers sought to escape. The Quaker movement was so widespread in England. That severe the punishment imposed to suppress it that 15,000 families are said to have been ruined by the fines, confiscations, and imprisonments.

Not a few Jersey Quakers were from Ireland, whether they had fled because the laws against them were less rigorously administered. The Newton settlers were joined by Quakers from Long Island, where, under the English law administered by the New York governors, they had also been fined and imprisoned, though with less severity than at home, for nonconformity to the Church of England. On arriving, the West Jersey settlers suffered some hardships during the year that had elapsed before a crop could be raised and a log cabin or house built. During that period, they usually lived in the Indian manner, in wigwams of poles covered with bark or in caves protected with logs on the steep banks of the creeks. Many of them lived in the villages of the Indians. The Indians supplied them with corn and venison; without this Indian help, they would have run a serious risk of starving, for they were not accustomed to hunting. They also had to thank the Indians for having, in past ages, removed so much of the heavy forest growth from the wide strip of land along the river that it was easy to start cultivation.

These Quaker settlers dealt very justly with the Indians, and the two races lived side by side for several generations. There is an instance recorded of the Indians attending with much solemnity the funeral of a prominent Quaker woman, Esther Spicer, for whom they had acquired great respect. The funeral was held at night, and the Indians in canoes, the white men in boats, passed down Cooper’s Creek and along the river to Newton Creek, where the graveyard was, lighting the darkness with innumerable torches, a strange scene to think of now as having been once enacted in front of the bustling cities of Camden and Philadelphia. Some of the young settlers took Indian wives, and that strain of native blood is said to show itself in the features of several families to this day.

Many letters of these settlers have been preserved, all expressing the greatest enthusiasm for the new country, for the splendid river better than the Thames, the excellent climate, and their improved health, and the immense relief of being away from the constant dread of fines and punishment, the chance to rise in the world, with large rewards for industry. They note the immense quantities of game, the Indians bringing in fat bucks every day, the venison better than in England, the streams full of fish, the abundance of wild fruits, cranberries, hurtleberries, the rapid increase of cattle, and the good soil.

A few details concerning some of the interesting characters among these early colonial Quakers have been rescued from oblivion. There is, for instance, the pleasing picture of a young man and his sister, convinced Quakers, coming out together and pioneering in their log cabin until each found a partner for life. John Haddon, from whom Haddonfield is named, bought a large tract of land but remained in England while his daughter Elizabeth came out alone to look after it. She was a strong, decisive character, and women of that sort have always been encouraged to independent action by the Quakers. She proved to be an excellent manager of an estate. The romance of her marriage to a young Quaker preacher, Estaugh, has been celebrated in Mrs. Maria Child’s novel The Youthful Emigrant. The pair became leading citizens devoted to good works and Quaker liberalism for many years in Haddonfield.

The ship Shields of Hull brought Quaker immigrants to Burlington. The story is told that in beating up the river, she tacked close to the relatively high bank with deep water frontage where Philadelphia was afterward established. Some passengers remarked that it was a good site for a town. The Shields, it is said, was the first ship to sail up as far as Burlington. Anchoring before Burlington in the evening, the colonists woke up the following day to find the river frozen hard so that they walked on the ice to their future habitations. Burlington was made the capital of West Jersey, a legislature was convened, and laws were passed under the “concessions” or constitution of the proprietors. Salem and Burlington became the ports of the little province, which was well underway by 1682 when Penn came out to take possession of Pennsylvania.

The West Jersey people of these two settlements spread eastward into the interior. Still, they were stopped by a great forest area known as the Pines, or Pine Barrens, of such heavy growth that even the Indians lived on its outer edges and entered it only for hunting. It was an irregularly shaped tract, full of wolves, bears, beaver, deer, and other game, and until recent years, has continued to attract sportsmen from all parts of the country. Starting near Delaware Bay, it extended parallel with the ocean as far north as the lower portion of the present Monmouth County and formed a region about 75 miles long and 30 miles wide. It was roughly the part of the old sandy shoal that first emerged from the ocean, and it has been longer above water than any other part of southern Jersey. The old name, Pine Barrens, is hardly correct because it implied something like a desert when the region produced magnificent forest trees.

The innumerable visitors who cross southern Jersey to the famous seashore resorts always pass through the remains of this old central forest and are likely to conclude that the monotonous low scrub oaks and stunted pines on sandy level soil, seen for the last two or three generations, were always there and that the ancient forest of colonial times was no better. But that is a mistake. The stunted growth now seen is not second growth but, in many cases, fourth, fifth, or more. The whole region was cut over long ago. The original growth, pine in many places, also consisted of tall timber of oak, hickory, gum, ash, chestnut, and numerous other trees, interspersed with dogwood, sassafras, and holly, and in the swamps, the beautiful magnolia, along with the valuable white cedar. DeVries, who visited the Jersey coast about 1632 at what is supposed to have been Beesley’s or Somer’s Point, describes high woods coming down to the shore. Even today, immediately back of Somer’s Point, there is a magnificent lofty oak forest accidentally preserved by the surrounding marsh from the destructive forest fires, and there are similar groves along the road towards Pleasantville. The finest forest trees flourish in that region wherever given a good chance. Even some of the beaches of Cape May had valuable oak and luxuriant growths of red cedar, and until a few years ago, there were fine trees, especially hollies, surviving on Wildwood Beach.

The Jersey white cedar swamps were, and still are, places of fascinating interest to the naturalist and the botanist. The hunter or explorer found them scattered almost everywhere in the old forest and near its edges, varying in size from a few square yards up to hundreds of acres. They were formed by little streams easily checked in their flow through the level land by decaying vegetation or dammed by beavers. They kept the water within the country, preventing all effects of droughts and stimulating the growth of vegetation which, by its decay, throughout the centuries, was steadily adding vegetable mold or humus to the sandy soil. Lumbering, drainage, and fires have largely stopped this process of building richer soil. While there are many of these swamps left, the appearance of numbers of them has vastly changed. When the white men first came, the great cedars three or four feet in diameter, which had fallen centuries before, often lay among the living trees, some buried deep in the mud and preserved from decay. They were invaluable timber, and digging them out and cutting them up became an important industry for over a hundred years. In addition to being used for boat building, they made excellent shingles that would last a lifetime. Indeed, the swamps became known as shingle mines, which was a good description. An important trade was developed in hogshead staves, hoops, shingles, boards, and planks, much of which went into the West Indian trade to be exchanged for rum, sugar, molasses, and negroes.

The great forest has long since been lumbered to death. The pines were worked for tar, pitch, resin, and turpentine until, for lack of material, the industry passed southward through the Carolinas to Florida, exhausting the trees as they went. The Christmas demand for holly has almost stripped the Jersey woods of these trees once so numerous. Destructive fires and frequent cutting keep the pine and oak lands stunted. Thousands of dollars worth of cedar springing up in the swamps are sometimes destroyed in a day. But efforts to control the fires so destructive not only to this standing timber but to the fertility of the soil, and attempts to reforest this country not only for the sake of timber but as an attraction to those who resort there in search of health or natural beauty, have not been vigorously pushed. The great forest has now, to be sure, been partially cultivated in spots, and the sand is used for large glass-making industries. Small fruits and grapes flourish in some places. At the northern end of this forest tract, the health resort known as Lake Wood was established to take advantage of the pine air. A little to the southward is the secluded Brown’s Mills, once so appealing to lovers of the simple life.

Lower Alloways Creek Quaker Meeting House, Hancocks Bridge, Salem County, New Jersey, by Jack Boucher.

Checked on the east by the great forest, the West Jersey Quakers spread southward from Salem until they came to the Cohansey, a large and beautiful stream flowing out of the forest and wandering through green meadows and marshes to the bay. So numerous were the wild geese along its shores and along the Maurice River farther south that the first settlers are said to have killed them for their feathers alone and thrown the carcasses away. At the head of navigation of the Cohansey was a village called Cohansey Bridge, and after 1765, Bridgeton, a name still borne by a flourishing modern town. Lower down near the marsh was the village of Greenwich, the principal place of business with foreign trade up to the year 1800. Some of the tea the East India Company tried to force on the colonists during the American Revolution was sent there and was duly rejected.

It is still a beautiful village, with its broad shaded streets like a New England town and its old Quaker meeting house. New Englanders from Connecticut, still infatuated with southern Jersey despite the rebuffs received in ancient times from Dutch and Swedes, finally settled near the Cohansey after it came under the control of the more amiable Quakers. There was also one place called Fairfield in Connecticut and another called New England Town.

The first churches of this region were usually built near running streams so that the congregation could procure water for themselves and their horses. Of one old Presbyterian Church, it used to be said that no one had ever ridden to it in a wheeled vehicle. Wagons and carriages were very scarce until after the Revolution. Carts for occasions of ceremony as well as utility were used before wagons and carriages. For a hundred and 50 years, the horse’s back was the best conveyance in the deep sand of the trails and roads. This was true of all southern Jersey. Pack horses and the backs of Indian and black slaves were the principal means of transportation on land. The roads and trails, in fact, were so few and so heavy with sand that water travel was very much developed. The Indian dugout canoe was adopted and found to be faster and better than heavy English rowboats. As the province was almost surrounded by water and was covered with a network of creeks and channels, nearly all the villages and towns were situated on tidewater streams, and the dugout canoe, modified and improved, was, for several generations, the principal means of communication.

Most of the old roads in New Jersey followed Indian trails. There was a trail, for example, from the modern Camden opposite Philadelphia, following Cooper’s Creek past Berlin, then called Long-a-coming, crossing the watershed, and then following Great Egg Harbor River to the seashore. Another trail, long used by the settlers, led from Salem up to Camden, Burlington, and Trenton, going around the heads of streams. It was afterward abandoned for the shorter route obtained by bridging the streams nearer their mouths. This old trail also extended from the neighborhood of Trenton to Perth Amboy near the mouth of the Hudson River and thus, by supplementing the lower routes, made a trail nearly the whole length of the province. As a Quaker refuge, West Jersey never attained the success of Pennsylvania. The political disturbances and the continually threatened loss of self-government in both the Jerseys were a serious deterrent to Quakers who, above all else, prized rights, which they found far better secured in Pennsylvania.

In 1702, when the two Jerseys were united into one colony under a government appointed by the Crown, those rights were more restricted than ever, and all hopes of West Jersey becoming a colony under complete Quaker control were shattered. Under Governor Cornbury, English law was adopted and enforced. The Quakers were disqualified from testifying in court unless they took an oath and were prohibited from serving on juries or holding any office of trust. Cornbury’s judges wore scarlet robes, powdered wigs, cocked hats, gold lace, and side arms; they were conducted to the courthouse by the sheriff’s cavalcade and opened court with a grand parade and ceremony. Such a spectacle of pomp was sufficient to divert the flow of Quaker immigrants to Pennsylvania, where the government was entirely in Quaker hands and where simple and serious ways gave promise of enduring and unmolested prosperity.

The Quakers had 30 meeting houses in West Jersey and 11 in East Jersey, which probably shows the proportion of Quaker influence in the two Jerseys. Many of them have since disappeared; some of the early buildings, to judge from the pictures, were of wood and not particularly pleasing in appearance. They were makeshifts, usually intended to be replaced by better buildings. Some substantial brick buildings of excellent architecture have survived, and their plainness and simplicity, combined with excellent proportions and thorough construction, indicate Quaker’s character. There is a particularly interesting one in Salem with a magnificent old oak beside it, another in the village of Greenwich on the Cohansey farther south, and another at Crosswicks near Trenton.

John Woolman was born in West Jersey near Mount Holly and lived there for a long time. He was a Quaker who became eminent throughout the English-speaking world for the simplicity and loftiness of his religious thought and his admirable style of expression. His Journal, once greatly and even extravagantly admired, still finds readers. “Get the writings of John Woolman by heart,” said Charles Lamb, “and love the early Quakers.’ He was among the Quakers, one of the first and perhaps the first earnest advocates of the abolition of slavery. The scenes of West Jersey and the writings of Woolman seem to belong together. Possibly, a feeling for the simplicity of those scenes and their life led Walt Whitman, who grew up on Long Island under Quaker influence, to spend his last years at Camden in West Jersey. His profound democracy, which was very Quaker-like, was more at home there, perhaps, than anywhere else.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Settling America – The Proprietary Colonies

Source: Johnson, Allen; Chronicles of America Series, Volume 8, Yale University Press, 1919