Chief Pontiac

By Henry Howe, 1857

In 1760, the French yielded to the English power in Canada and on the western waters. Three days after the fall of Montreal, Major Robert Rogers was dispatched with forces to take possession of the French posts along the southern shore of Lake Erie and at Detroit, Michigan.

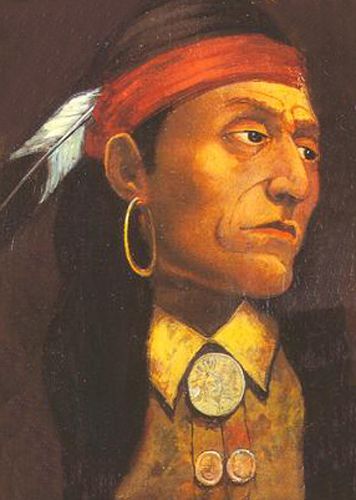

At this period, there sprung upon the stage one of the most remarkable Indians in the annals of American History. It was Pontiac, the chief of the Ottawa tribe and the principal sachem of the Algonquian Confederacy. His noble form, commanding address, and proud demeanor distinguished him. To these qualities, he united a lofty courage and a pointed and vigorous eloquence that won the confidence of all the Great Lakes Indians and made him a marked example of that grandeur and sublimity of character sometimes found among the Indians of the American forests. He had jealously watched the progress of the English arms and their rapid encroachments upon the lands of his people.

When Pontiac first heard of the approach of Major Rogers with a detachment of English troops, he roused like a lion from his den and dispatched a messenger, who met Rogers on November 7, 1760, at the mouth of Chogage River, with a request to halt until Pontiac, the king of the country, should come up.

At the first salutation, Pontiac demanded of Rogers, the business on which he came, and asked him how he dared to enter his country without his permission. Rogers informed him that he had no design against the Indians; his only objective was to remove the French from the country, who had been an obstacle to mutual peace and commerce between the Indians and the English. The next morning, Pontiac and the English commander, by turns, smoked the calumet, and Pontiac informed Rogers that he should protect his party against the attacks of the Indians who were collected to oppose his progress at the mouth of Detroit River.

Having obtained peaceable possession of Detroit, Rogers made peace with the neighboring tribes and, leaving Captain Donald Campbell in charge of the fort, departed on December 21 for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The Indians in this region, at first, regarded the English as intruders, and the smile which played upon the countenance of Chief Pontiac when he first met the detachment of Major Rogers on the shore of Lake Erie, only tended to conceal a settled hatred — as the setting sunbeam bedazzles the distant thundercloud. He had made professions of friendship to the English as a matter of policy until he could have time to plot their destruction.

The plan of operations adopted by Pontiac for effecting the extinction of the English power evinced extraordinary genius, courage, and energy of the highest order. It was a sudden and cotemporaneous attack upon all the British posts upon the Great Lakes — at St. Joseph, Ouiatenon, Green Bay, Michiliraackinac, Detroit, the Maumee, and the Sandusky — and also upon the forts at Niagara, Presque Isle, Le Boeuf, Venango, and Pittsburgh; the last four of which were in Western Pennsylvania. If the surprise could be simultaneous so that every English banner waved upon a line of thousands of miles should be prostrated simultaneously, the garrisons would be unable to exchange assistance. On the other hand, the failure of one Indian detachment would not affect discouraging the other. The war might probably begin and terminate with the same single blow; then, Pontiac would again be the Lord and King of the broad land of his ancestors.

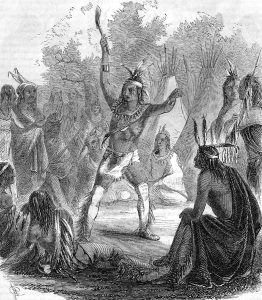

He first called together the Ottawa, and the plan was disclosed and enforced with all the cunning and eloquence he could master. He appealed to their fears, hopes, ambition, patriotism, hatred of the English, and love for the French. Having warmly engaged them in the cause, he assembled a grand council of the neighboring tribes at the River Aux Ecorces. With a profound knowledge of the Indian character, aware of the great powers of superstition over their minds, he related, among other things, a dream in which he said the Great Spirit had secretly disclosed to a Delaware Indian the conduct he expected his red children to pursue. This dream was strikingly coincident with the plans and projects of the chieftain himself. “And why,” concluded the orator, “said the Great Spirit indignantly to the Delaware, do you suffer those dogs in red clothing to enter your country and take the land I have given you? Drive them from it! Drive them! When you are in distress, I will help you.”

The effect of this speech was indescribable. The name of Pontiac alone was enough, but the Great Spirit was for them — it was impossible to fail. A plan of campaign was concerted on the spot, and for a thousand miles, on the lake frontiers, and even down to the borders of North Carolina, the tribes joined in the grand conspiracy.

Meanwhile, peace reigned on the frontiers. The unsuspecting traders journeyed from village to village; the soldiers in the forts shrunk from the sun of early summer and dozed away the day; the frontier settler sang in fancied security, sowed his crop, or watched the sunset through the girdled trees, mused upon one more peaceful harvest, and told his children of the horrors of the long war, now — thank God! — over. The trees had left from the Alleghanies to the Mississippi River, and all was calm life and joy. But, even then, through the gloomy forests, bands of sullen red men journeyed like the gathering of dark clouds for a horrid tempest.

Surprise of the English Forts

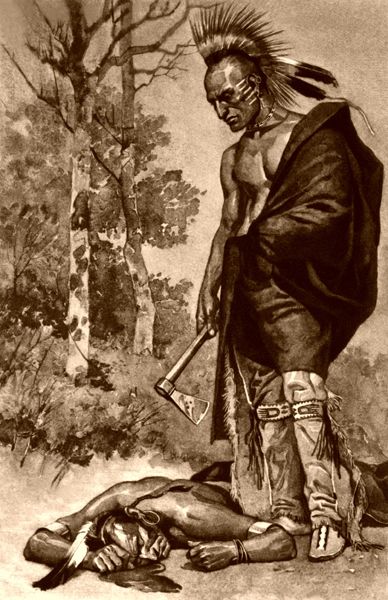

The Maumee post, Presque Isle, Niagara, Pitt, Ligonier, and every English fort, was hemmed in by mingled tribes. At last, the day came. The traders everywhere were seized with their goods, and more than 100 put to death. Nine British forts yielded instantly, and the Indian drank, “scooped up in the hollow of joined hands,” the blood of many a Briton. More than 20,000 people were driven from their homes, and horrible, unparalleled devastations were committed on the frontiers of Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York. Most, if not all of the forts which fell were taken by stratagem — pre-concerted by the mastermind of Pontiac. Generally, the commanders were first secured by parties admitted into the forts under the pretense of business or friendship. At Maumee, the officer was betrayed by an Indian woman, who, by piteous entreaties, persuaded him to go some 200 yards with her to the succor, as she stated, of a wounded man who was dying; the Indians waylaid and shot him.

In some few of the forts, individuals escaped, but, too generally, all were massacred. At Presque Isle, three Indians appeared in holiday dress. They persuaded the commander and clerk to accompany them to the canoes of their hunting party, as they said, about a mile distant, to examine and purchase a lot of peltries. In their absence, about 150 Indians advanced toward the fort, each with a bundle of furs on his back, which they stated the commandant had bought and ordered them to bring in. The stratagem succeeded. When they were all within the fort, the work of an instant threw off the packs and the short cloaks which covered their tomahawks, scalping knives, and rifles, the last having been sawed off short for concealment. Resistance was useless, and the work of death and torture rapidly proceeded until all, except two of the inmates of the garrison, had passed to the eternal world.

The forts of Bedford, Ligonier, Pitt in Pennsylvania, and Fort Detroit, in present-day Michigan were saved with great difficulty. The Indians invested Fort Pitt with a strong force, information that had been conveyed to Lord Jeffrey Amherst; he dispatched Colonel Henry Boquet to its relief with two regiments of regulars. He was fiercely attacked at Bushy Run by the Indians and lost over 100 men killed and wounded, but he defeated the Indians with great difficulty and saved the fort. Fort Ligonier was bravely defended by Lieutenant Archibald Blane and his little garrison.

Massacre at Michilimackinac

The particulars of the taking of Fort Michilimackinac are more fully known. Standing on the south side of the strait connecting Lakes Huron and Michigan, that fort was one of the most important posts on the frontier. It was the great place of deposit and departure between the upper and lower countries, the great assembling point of the Indian traders on their voyages to and from Montreal, Canada. About 30 houses and families were within the enclosure of the stockade, and the garrison, under the command of Major George Etherington, numbered between 90 and 100 men.

The capture of this important station was entrusted to the Chippewa, assisted by the Sac. The King’s birthday, June 3, having arrived, a game of lacrosse was proposed by the Indians.

This is played with a bat and ball about four feet long, curved, and terminating in a racket. Two posts are placed in the ground, half a mile apart. Each party has its post, and the game consists of throwing up to the adversary’s post; the ball at the beginning is placed in the middle of the course.

The policy of this expedient for surprising the garrison will appear clearly when it is understood that the game is necessarily attended with much violence and noise and, in the ardor and heat of the contest, would be diverted in any direction the successful party should choose. The design of the Indians, in this case, was to throw the ball over the pickets, and in the excitement of the game, it was but natural that all the Indians should rush after it. The Indians had persuaded many of the garrison and settlers to come voluntarily without the pickets to witness the game, which was said to be played for a high wager. Among these was Major Etherington, the commandant, who laid a wager on the side of the Chippewa. Fewer than 400 Indians were engaged on both sides, and consequently, when possession of the fort was gained, the situation of the English must be desperate indeed. The match commenced without the fort with great animation. Henry, an Indian trader, who gives the account, had been occupied within the fort for about half an hour writing when he suddenly heard a loud Indian war cry and a noise of general confusion. Going instantly to his window, he saw a crowd of Indians within the fort, furiously cutting down and scalping every Englishman they found: and he could plainly witness the last struggles of some of his particular acquaintances.

He had, in the room, a fowling piece loaded with swan shot. This he immediately seized and held it for a few minutes, expecting to hear the fort drum beat to arms. In this dreadful interval, he saw several of his countrymen fall; and more than one struggling between the knees of the Indians, who, holding them in this manner, scalped them while yet alive. At length, disappointed in the hope of seeing any resistance made on the part of the garrison and sensible that no effort of his single arm could avail against 400 Indians, he turned his attention to his own safety. Seeing several of the Canadian villagers looking out composedly upon the scene of blood — neither opposing the Indians nor molested by them — he conceived the hope of finding security in one of their houses. He immediately climbed over a low fence, separating his dooryard and that of his next neighbor, Monsieur Langlade. Entering his house precipitately, he found the whole family gazing upon the horrible spectacle before them. He begged Langlade to put him in some place of safety until the heat of the affair should be over, an act of charity that might preserve him from the general massacre. Langlade looked at him for a moment while he spoke and then turned again to the window, shrugging his shoulders and intimating that he could do nothing for him.

Henry was now ready to despair, but at this moment, a Pani woman, a slave of Monsieur Langlade, beckoned him to follow her. She guided him to a door she opened, desiring him to enter and telling him that it led to the garret, where he must go and conceal himself. Scarcely yet lodged in this shelter, such as it was, Henry felt an eager desire to know what was passing without. His desire was more than satisfied by his finding an aperture in the loose board walls of the house, which afforded him a full view of the area of the fort. Here, he beheld with horror, in shapes the foulest and most terrible, the ferocious triumphs of the Indians. The dead were scalped and mangled; the dying were writhing and shrieking under the unsatiated knife and the reeking tomahawk; and from the bodies of some ripped open, their butchers were drinking the blood, scooped up in the hollow of joined hands, and quaffed amid shouts of rage and victory. In a few minutes, which seemed to Henry scarcely one, every victim, who could be found, being destroyed, there was a general cry of “all is finished.” At this moment, Henry heard some Indians enter Langlade’s house. He trembled and grew faint with fear.

Pontiac’s Rebellion

As the floor consisted only of a single layer of boards, he overheard everything that passed. The Indians inquired, on entering, if there were any Englishmen about. Langlade replied that he could not say — he did not know of any — as in fact he did not — “they could search for themselves and be satisfied.” The state of Henry’s mind may be imagined when immediately upon this reply, the Indians were brought to the garret door. Luckily some delay was occasioned — through the management of the Pani woman — she had locked the door, and perhaps it was by the absence of the key. Henry had sufficient presence of mind to improve these few moments in looking for a hiding- place. This, he found in the corner of the garret, among a heap of such birch bark vessels as are used in making maple sugar; and he had not completely concealed himself when the door opened, and four Indians entered, all armed with tomahawks, and all besmeared with blood from head to foot.

The die appeared to be cast. Henry could scarcely breathe, and he thought that the throbbing of his heart occasioned a noise loud enough to betray him. The Indians walked about the garret in every direction; one of them approached him so closely that at one moment, had he put forth his hand, he must have touched him. Favored, however, by the dark color of his clothes, and the want of light in the room, which had no window, he still remained unseen. The Indians took several turns about the room — entertaining Monsier Langlade all the while with a minute account of the day’s proceedings; and, at last, returned downstairs. There was, at the time, a mat in the room, and Henry fell asleep; he was finally awakened by the wife of Langlade, who had gone up to stop a hole in the roof. She was surprised to see him there — remarked that the Indians had killed most of the English but that he might hope to escape. He lay there during the night.

At length, the wife of Langlade informed the Indians of Henry’s concealment, fearing, as she subsequently alleged, that if they should find him secreted in her house, they would destroy her and her children. Unlocking the door, she was followed by half a dozen Indians, naked down to their waist and intoxicated. On entering, their chief, Wenniway, a ferocious man of gigantic stature, advanced with lips compressed, seized Henry by one hand, and with the other held a large carving knife, as if to plunge it into his heart while his eyes were steadfastly fixed on his. Gaining momentarily, he dropped his arm and said, “I won’t kill you.” He then at once adopted him in the place of a brother whom he had lost in the wars with the English, and Henry was eventually ransomed.

Seventy of the troops were massacred; of these, several bodies were boiled and eaten. The remainder and those taken at the fall of forts, St. Joseph, and Green Bay were restored after the war.

Siege of Detroit (May 7, 1763)

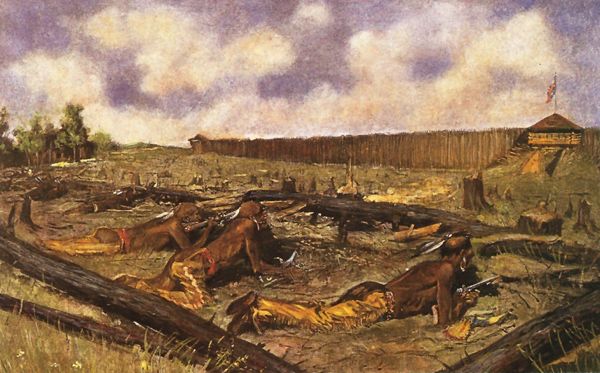

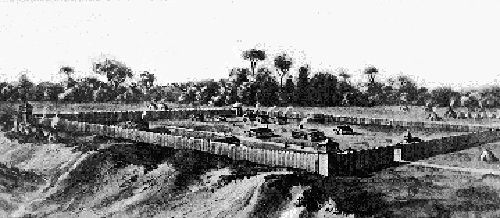

Fort Detroit, Michigan

Detroit was a more important situation even than Fort Michiliinackinac. Besides an immense quantity of valuable goods, it was stated that over two million dollars were known to be stored there. If captured, it would unite the separate lines of operation pursued by the Indian tribes above and below the Great Lakes. Under these circumstances, its reduction was undertaken by Chief Pontiac in person. The garrison numbered 130 men, including officers, and about 40 individuals in the village was engaged in the fur trade.

Such was the situation of Detroit when the Ottawa chieftain, having completed his arrangements on the 7th of May, presented himself at the gates of the town with a force of about 300 Indians, chiefly Ottawa and Chippewa, and requested a council with Major Henry Gladwyn, the commandant. He expected, under this pretext, to gain admittance for himself and a considerable number of attendants, who accordingly were provided with rifles, sawed-off so short as to be concealed under their blankets. At a given signal, which was to be the presentation of a wampum belt, in a particular manner, by Pontiac, to the commandant, during the conference, the armed Indians were to massacre all the officers, then open the gates to admit the main body of the warriors, who were to be waiting without for the completion of the slaughter and destruction of the fort.

However, an Indian woman betrayed the secret. The commandant had employed her to make him a pair of moccasins out of elk skin and brought them into the fort; finished on the evening, Pontiac made his appearance and application for a council. The Major paid her generously, requested her to make more from the residue of the skin, and then dismissed her. She went to the outer door, but there stopped and loitered about as if her errand was still unperformed. A servant asked her what she wanted, but she made no answer. The Major observed her and ordered her to be called in when, after some hesitation, she replied to his inquiries that as he had always treated her kindly, she did not like to take away the elk skin he valued so highly she could never bring it back. The commandant’s curiosity was excited, and he pressed the examination until the woman, at length, disclosed everything which had come to her knowledge.

Her information was not received with implicit credulity, but the Major thought it prudent to employ the night to take active defense measures. A strict guard was kept upon the ramparts during the night; it is apprehended that the Indians might anticipate the preparations now known to have been made for the next day. Nothing, however, was heard after dark except the sound of singing and dancing in the Indian camp, which they always indulged in upon the eve of any great enterprise.

In the morning, Pontiac and his warriors sang their war song, danced their war dance, and then repaired to the fort. They were admitted without hesitation and conducted to the council house, where Major Gladwyn and his officers were prepared to receive them. They perceived unusual activity and movement among the troops at the gate as they passed through the streets. The garrison was under arms, the guards were doubled, and the officers were armed with swords and pistols.

Pontiac inquired of the British commander what was the cause of this unusual appearance. He answered that keeping the young men to their duty was proper, lest they become idle and ignorant. The council’s business commenced, and Pontiac addressed Major Gladwyn. His speech was bold and menacing, and his manner and gesticulations vehement, and they became still more so as he approached the critical moment. When he was upon the point of presenting the belt to Major Gladwyn, and all was a breathless expectation, the drums at the door of the council house suddenly rolled the charge, the guards leveled their pieces, and the officers drew their swords from their scabbards. Pontiac, whose eagle eye had never quailed in battle, turned pale and trembled. This unexpected and decisive proof that his treachery was discovered entirely disconcerted him. He delivered the belt in the usual manner and thus failed to give his party the concerted signal of attack. At the same time, his warriors stood looking at each other in astonishment; Major Gladwyn immediately approached Pontiac and, drawing aside his blanket, discovered the shortened rifle and then, after stating his knowledge of his plan, advised him to leave the fort before his young men should discover their design and massacre them. He assured him, as he had promised him safety that his person should be held unharmed until he had advanced beyond the pickets. The Indians immediately retired, and as soon as they had passed the gate, they yelled and fired upon the garrison: Several persons living without the fort were then murdered, and hostilities commenced.

The cannibalism of the Indians at this time may be learned from the fact that a respectable Frenchman was invited to their camp to partake of some soup. Having finished his repast, he was told that he had eaten a part of an English woman, Mrs. Turnbell, who had been among the victims, a knowledge that probably, did not improve his digestion.

The Indians soon stationed themselves behind the buildings, outside the pickets, and kept a constant, though ineffectual, fire upon the garrison. All the means that the savage mind could suggest were employed by Pontiac to demolish the settlement of Detroit. During the siege, which lasted more than two months, the Indians endeavored to make a breach in the pickets and were aided by Major Gladwyn, who, as a stratagem, had ordered his men to cut also on the inside; this was soon accomplished, and the breach immediately filled with Indians. At this instant, a cannon was discharged upon the advancing Indians, creating destructive havoc. After that period, the fort was merely invested; supplies were cut off, and the English were greatly distressed from the diminution of their rations and the constant watchfulness required to prevent surprise.

While the siege was in progress, twenty batteaux, with 97 troops and stores, on their way from Niagara to Detroit, arrived at Point Pelee, on Lake Erie, about 50 miles easterly from Detroit. Apprehending no danger, the troops landed and encamped. The Indians, who had watched their movements, attacked them about dawn, and massacred or took prisoners all, except 30, who succeeded in escaping, in a barge, across the lake to Sandusky Bay. The Indians placed their prisoners in the batteaux and compelled them to navigate them on the Canadian side of the lake and river toward Detroit. As the fleet of boats was discovered coming around the point of the Huron church, the English assembled on the ramparts to witness the arrival of their friends, but they were only greeted by the death song of the Indians, which announced their fate. The light of hope flickered on their countenances only to be clouded with the thick darkness of despair. It was their barges, but they had the Indians filled with the scalps and prisoners of the detachment. Except for a few who escaped when opposite the town, the prisoners were taken to Hog Island, above Detroit, massacred, and scalped.

A few weeks later, a Niagara vessel with 60 troops, provisions, and arms entered the Detroit River. To board her as she ascended, the Indians repaired to Fighting Island, just below the city, which she soon reached, and then, for want of wind, was obliged to anchor. The Captain concealed his men in the hold, and in the evening, the Indians proceeded in silence to board the vessel from their canoes while the men on board were required to take their stations at the guns. The Indians approached near the side when a blow gave the signal for discharge upon the mast with a hammer. Many of the Indians were killed and wounded, and the remainder, panic-stricken, paddled away in their canoes with all speed. After this, Pontiac endeavored to burn the vessels that lay anchored before Detroit, for which object he made an immense raft from several barns, which he pulled down for that purpose and filled with a pitch and other combustibles. It was then towed upriver and set on fire under the supposition that the current would float the blazing mass against the vessels. The English foiled this attempt by anchoring boats, connected by chains, above their vessels.

During the siege, the body of the French people in and around Detroit was neutral. In a speech of great eloquence and power, Pontiac endeavored to persuade them to join his cause. But, his solicitations did not prevail. Shortly after, on June 3rd, the French had a double reason for maintaining neutrality in the news that they received of the peace treaty, by which France ceded their country to England. On the 29th of July, 300 regular troops, under Captain James Dalyell, arrived, in gunboats, from Canada. On the night of the 30th, Captain Dalyell, with over 200 men, attempted to surprise Pontiac’s camp. That chieftain having, by some means, been apprised of the contemplated attack, was prepared and lay in ambush with his Indians, concealed behind high grass, at the Bloody Bridge, one and a half miles above Detroit. As the English reached the bridge, a sudden and destructive fire was poured upon them. This threw them into the utmost confusion. The attack in the darkness from an invisible force was critical. The English fought desperately but were obliged to retreat, with the loss of their commander and over 60 in killed and wounded.

The operations of Pontiac in this quarter soon called for the efficient aid of government, and during the season, General John Bradstreet arrived to the relief of the posts on the lakes with an army of 3,000 men. The tribes of Pontiac, excepting the Delaware and the Shawnee, finding that they could not successfully compete with such a force, laid down their arms and made peace. Pontiac, however, took no part in the negotiation and retired to Illinois, where he was, a few years after, assassinated by an Indian of the Peoria tribe.

By Henry Howe, 1857 – Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

About the Author and Article: This article was a chapter in Henry Howe’s book Historical Collections of the Great West, published by George F. Tuttle, of New York, in 1857. Henry Howe (1816 -1893) was an author, publisher, historian, and bookseller. Born in New Haven, Connecticut, his father owned a popular bookshop and a publisher. Henry would write histories of several states. His most famous work was the three-volume Historical Collections of Ohio. As he collected facts for his writing, he also drew sketches which helped create interest in his work. The article as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been edited for the modern reader; however, the content remains essentially the same.

Also See: