Samuel Parris was the Puritan minister in Salem Village, Massachusetts, during the Salem witch trials and the father of one of the afflicted girls, Elizabeth Parris, and the uncle of another — Abigail Williams.

Samuel was born in London, England, in 1653, the son of cloth merchant Thomas Parris, who also had interests in the island colony of Barbados. Samuel was sent to Massachusetts to study at Harvard when he grew up. In 1673, while he was still in college, his father died, leaving the 20-year-old with a plantation in Barbados. After graduating, Parris moved to the island, where he leased out the family sugar plantation and settled in Bridgetown. There, he established himself as a credit agent for other sugar planters.

In 1680, after a hurricane hit Barbados, much of his property was damaged. He then left the island, taking two slaves, Tituba and John Indian, with him. He then settled in Boston, where he once again tried establishing himself as a merchant. He purchased a wharf and warehouse and attended Boston’s First Church, where he met Elizabeth Eldridge. The two would soon marry and have three children, Thomas, Elizabeth, and Susannah. His slaves, Tituba and John Indian, remained a part of his household. Dissatisfied with the life of a merchant, Parris considered a change in vocation, and in 1686, he began substituting for absent ministers and speaking at informal church gatherings.

After the birth of their third child, the Reverend Parris began formal negations with Salem Village to become the village’s new minister. At this time, Salem Village was known to be contentious, described by residents of neighboring towns as quarrelsome. It had also already been through three ministers, who had all departed after having issues with the congregation. Though Parris was aware of the village conflicts that had taken place in the last several years, his Puritan beliefs that each person was responsible for monitoring his neighbor’s piety made him feel that conflict was inevitable.

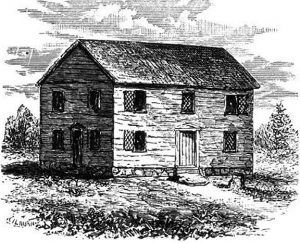

On June 18, 1689, at a general meeting of all villagers, it was agreed to hire Samuel Parris at an annual salary of £66, and the villagers would provide firewood for both the church and parsonage. At a later meeting, the villagers agreed they would also provide Parris and his heirs the village parsonage, a barn, and two acres of land. Parris agreed, and he and his family immediately moved to Salem Village, settling into the parsonage and beginning his ministerial duties that same month. To the parsonage, Reverend Parris brought his wife, Elizabeth, his nine-year-old daughter Elizabeth, his 11-year-old niece, Abigail Williams, and his slaves, Tituba and John Indian.

On November 19, 1689, the Salem Village church charter was finally signed, and Reverend Samuel Parris became Salem Village’s first ordained minister. His ministry began smoothly, but as Parris revealed his beliefs and traits, several Salem Villagers, including a few church members, did not like what they saw. A severe and dedicated minister, he combined his evangelical enthusiasm to revitalize religion in Salem Village with psychological rigidity and theological conservatism.

While the Salem Towne Church and most Puritan churches of the time were relaxing their standards for church membership, Parris held rigid to traditional strict standards, which required that members be baptized and make a public declaration of experiencing God’s free grace to become full members. Most village church members were happy with Parris’s traditionalism, which elevated their status by sharply distinguishing them from non-church members. But, a minority dissented and found allies among non-members, who constituted a large and influential part of the Salem Village community.

Suddenly, Parris also found himself amid contract disputes with the Salem Village Church council members. The council alleged that the contract, seemingly never formalized, only provided Parris with the parsonage and lands only so long as he remained the minister, rather than Parris’ beliefs that the contract granted Parris outright ownership of the house and lands. At the same time, Parris was planning to refurbish the meeting house commensurate with its new status as a full church. But, to many, this signaled a more intrusive and expensive church than some villagers wished.

By the fall of 1691, only two years after his ordination, Parris’s ritual orthodoxy, overbearing disposition, and the disputed contract had caused the village and church to once again break into factions. Church attendance fell, and village officials refused to provide firewood to warm the church or Parris’s house. Matters turned worse when the village chose a new Committee of Five in October 1691, which announced its refusal to relinquish the ministry house and land to Parris or to collect taxes for his salary, leaving it to the villagers to pay by “voluntary contributions.” Parris then called upon church members to make a formal complaint to the County Court against the committee’s neglect of the church. The factional fighting also began in his weekly sermons as a battle between God and Satan.

That winter, Samuel’s daughter, Elizabeth Parris, and her cousin, Abigail Williams, began to undertake experiments in fortune telling, mainly focusing on their future social status and potential husbands. They were quick to share their game with other young girls in the area, even though the practice of fortune-telling was regarded as a demonic activity. By January 1692, nine-year-old Elizabeth appeared to be consumed with a secret preoccupation and was forgetting errands and unable to concentrate. She then began to act in strange ways, barking like a dog when her father would rebuke her, screaming wildly when she heard the “Our Father” prayer, and once, hurling a Bible across the room. After these episodes, she sobbed distractedly and spoke of being damned, perhaps because of her practice of “fortune telling.”

The Reverend Samuel Parris believed prayer could cure her odd behavior, but his efforts were ineffective. In fact, her actions got worse. Soon, she was contorting her body into odd postures, consistently spouting foolish and ridiculous speeches, and generally having fits. The Reverend Parris consulted other ministers, who would not explain her actions. But, when he brought in the local doctor, William Griggs, he suggested that her malady must result from witchcraft. Parris then organized prayer meetings and days of fasting in an attempt to alleviate Elizabeth’s symptoms. But, the frenzy just spread. Soon, Elizabeth’s cousin, Abigail Williams, was also having fits, followed by some of their friends, including Ann Putnam, Jr. and Mary Walcott. Since the sufferers of witchcraft were believed to be the victims of a crime, the community set out to find the perpetrators. On February 29, 1692, under intense adult questioning, Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams named Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba as their tormentors.

Parris’ preaching had a significant hand in creating the divisions within the village that contributed to the accusations of 1692. During the crisis, he declared the church under siege by the Devil, who was assisted by “wicked & reprobate men.” Parris began to draw “battle lines” between those who supported him and those who didn’t, who were undoubtedly the very ones he had called “wicked & reprobate.” The accusations against the opposing factions of Salem Village began in earnest and soon spread to nearby towns, including Andover, Beverly, Topsfield, Wenham, and others.

When the trials began, the Reverend Samuel Parris would submit complaints, serve as a witness, testify against many accused, and sometimes serve as the record keeper of the events. By the end of May 1692, more than 150 “witches” had been jailed, and by September, 19 people had refused to confess and were hanged, and another had been pressed to death for refusing to make a plea. By October, however, cooler heads began to prevail, and the court disallowed “spectral evidence.” The affair wouldn’t end until May 1693, when the accused were finally released from jail.

Though the hysteria had finally ended, Salem Village was still divided, and many were even more dissatisfied with the Reverend Parris. However, in 1695, two years after the end of the trials, Parris still garnered a majority of town support. But, over time, the families of those accused, especially those who had been executed, would push him out. Rebecca Nurse’s family and others directly accused Parris of providing names to the court, and many people had strong misgivings about his place in the trials. Some villagers brought charges against him for his part in the trials, leading him to apologize for his error. Samuel’s wife died in 1696 at the age of 48 and is buried in the Danvers Cemetery.

Despite the intense dislike of many Salem villagers, Parris stayed on until 1697, when he accepted another preaching position in Stow, Massachusetts. He would later live in Watertown and Concord, where he worked as a trader and a licensed retailer. Somewhere along the line, he would marry for a second time to Dorothy Noyes and the couple would have four children. He began preaching in Dunstable in 1708, which he continued until 1712. From there, he moved to Sudbury, where he worked as a farmer and, sometimes, as a school teacher. He died in Sudbury on February 27, 1720.

The Reverend Joseph Green replaced Parris in 1697, a man who genuinely wanted to heal Salem and started the village on the long and uncertain road to recovery.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

Also See:

Procedures, Courts & Aftermath