by Matt Doherty

Coined in 1845, the doctrine “Manifest Destiny” set into motion the western migration of thousands of Americans seeking opportunity. In 1848, the defeat of Mexico in the Mexican-American War and the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo connected America to both coasts, acquiring a 525,000 square mile tract of land that is today California, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming. The building of the transcontinental railroad that followed in 1860 accelerated the rapidly expanding westward migration across America. Now, telegraph wires and train tracks stretched from coast to coast. The tipis and vast bison herds that once covered the landscape had all but vanished, replaced by homesteads, sheep, and cattle.

By the 1890s, the American West’s wildest days were coming to a close. However, a handful of places remained yet to be tamed, and the Corrumpa Valley was one of those places. The very name Corrumpa was a Native American word meaning “Wild. “ It was here, amidst the sandstone canyons of northeastern New Mexico, that the renegade wolf, Lobo, and his pack of outlaws would make their last stand.

Compared to the hardy bison that wolves once relied on as one of their main food source, the docile cattle that now replaced them didn’t stand a chance, and the rancher’s losses began stacking up. It is estimated Lobo’s pack killed two thousand head of cattle over a five-year span.

The old idea that a wolf was constantly in a starving state and, therefore, ready to eat anything was as far as possible from the truth in this case, for they were always sleek and well-conditioned and were, in fact, most fastidious about what they ate. Their choice and daily food was the tenderer part of a freshly killed yearling heifer. They disdained an old bull or cow, and though they occasionally took a young calf or colt, it was quite clear that veal or horseflesh was not their favorite diet. It was also known that they were not fond of mutton, although they often amused themselves by killing sheep.

One night in November 1893, the white-female wolf sheepherders called Blanca and the old yellow wolf killed 250 sheep, leaving the mutton to spoil. The enormous loss of livestock lead to an all out war waged on Lobo’s band and a $1000 to anyone who could kill the leader of the outlaws.

Over the next five years, several men would attempt to collect, but none were successful. Finally, the desperate cattlemen and sheepherders enlisted the help of world-renowned trapper Ernest Seton. Accepting the challenge, Seton arrived in New Mexico eager to collect the $1,000 Seton, expecting to make short work of the band of outlaws; after all, he literally wrote the book on trapping wolves.

It didn’t take long for the seasoned trapper’s confidence to waiver as he soon realized he drastically underestimated his foe. Every time he set his trap, he returned to find that Lobo had dug up and defiantly defecated on every one of them. Changing his plans, Seton turned to poisoned chunks of meat strategically placed across the valley, only to find the poisoned meat piled up and defecated on.

The days turned into weeks and the weeks to months, and fall gave way to winter, and Lobo still remained large. Discouraged and near accepting defeat, Seton was out of ideas, having exhausted every trick in his book. Then, as he followed Lobo’s tracks, skirting the massive flock of Sandhill Cranes gathered along the creek, he finally got the break he was looking for. He noticed a smaller set of tracks close to Lobo at all times; then, he realized Lobo was in love. The white female wolf the sheepherders called Blanca was his weakness and would be his downfall.

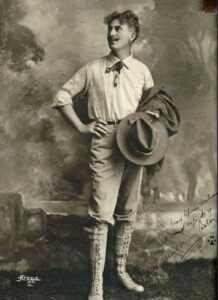

Lobo’s mate Blanca, “Meaning white in Spanish,” a name given to her by local sheepherders for her white coat.

Seton set his sights on Blanca, placing several traps in a narrow passage and a cow head at the end, thinking Blanca would fall for the bait that Lobo had thus far managed to avoid. Finally, Seton succeeded. While trying to investigate Seton’s planted cow head, Blanca became trapped. When Seton found her, she was whining with Lobo by her side. Lobo ran to a safe distance and watched as Seton and his partner killed Blanca and tied her to their horses. Seton heard Lobo’s howls for two days afterward. Seton described Lobo’s calls as having “an unmistakable note of sorrow in it… It was no longer the loud, defiant howl but a long, plaintive wail.” Although Seton felt remorse for the grieving wolf, he continued his plan to capture Lobo.

Despite the danger, Lobo followed Blanca’s scent to Seton’s ranch house, where they had taken the body. After spotting Lobo wandering near his ranch house, Seton set more traps, using Blanca’s body to scent them. Before this point, Lobo had not revealed himself to Seton even once since he arrived at the Currumpaw Valley. But now, Lobo’s grief had clearly taken over and dulled his sense of caution. On January 31, 1894, Lobo was caught, with each of his four legs clutched in a trap. The following is as told by Seton;

”Of course, I had my rifle as a last resource, but I did not wish to spoil his royal hide, so I galloped back to the camp and returned with a cowboy and a fresh lasso. We threw to our victim a stick of wood, which he seized in his teeth, and before he could relinquish it, our lassoes whistled through their air and tightened on his neck. Yet before the light had died from his fierce eyes, I cried, “Stay, we will not kill him; let us take him alive to the camp.” He was so completely powerless now that it was easy to put a stout stick through his mouth, behind his tusks, and then lash his jaws with a heavy cord, which was also fastened to the stick. The stick kept the cord in, and the cord kept the stick in, so he was harmless. As soon as he felt his jaws were tied, he made no further resistance and uttered no sound but looked calmly at us and seemed to say, “Well, you have got me at last; do as you please with me.” And from that time, he took no more notice of us.

On January 31, 1894, Lobo, the leader of one of the last packs of wolves in the Americas, was caught by Ernest Seton’s traps in the Currumpaw Valley, Union County, New Mexico.

We tied his feet securely, but he never groaned, growled, nor turned his head. Then, with our united strength, we were just able to put him on my horse. His breath came evenly as though sleeping, and his eyes were bright and clear again but did not rest on us. Afar on the great rolling mesas they were fixed, his passing kingdom, where his famous band was now scattered. And he gazed till the pony descended the pathway into the cañon, and the rocks cut off the view.

By traveling slowly, we reached the ranch in safety, and after securing him with a collar and a strong chain, we staked him out in the pasture and removed the cords. Then for the first time I could examine him closely, and proved how unreliable is vulgar report when a living hero or tyrant is concerned. He had not a collar of gold about his neck, nor was there on his shoulders an inverted cross to denote that he had leagued himself with Satan. But I did find on one haunch a great broad scar that tradition says was the fang mark of Juno, the leader of Tannerey’s wolf-hounds — a mark which she gave him the moment before he stretched her lifeless on the sand of the cañon.

I set meat and water beside him, but he paid no heed. He lay calmly on his breast and gazed with those steadfast yellow eyes away past me down through the gateway of the cañon, over the open plains — his plains — nor moved a muscle when I touched him. He was still gazing fixedly across the prairie when the sun went down. I expected he would call up his band when night came and prepare for them, but he had called once in his extremity, and none had come; he would never call again.

A lion shorn of his strength, an eagle robbed of his freedom, or a dove bereft of his mate, all die, it is said, of a broken heart; and who will aver32 that this grim bandit could bear the three-fold brunt, heart-whole? This only I know, that when the morning dawned, he was lying there still in his position of calm repose, but his spirit was gone — the old king-wolf was dead.

I took the chain from his neck, and a cowboy helped me to carry him to the shed where lay the remains of Blanca, and as we laid him beside her, the cattleman exclaimed: “There, you would come to her, now you are together again.”

Seton’s experience on the Corrumpa changed his views on man’s relationship with wildlife, later becoming an advocate for the wolf, saying, “Ever since Lobo, my sincerest wish has been to impress upon people that each of our native wild creatures is in itself a precious heritage that we have no right to destroy or put beyond the reach of our children.” He met with Theodore Roosevelt, discussing the need to protect the American wolf. The story Seton wrote recounting the ordeal, called “Lobo, King of the Currumpaw.” was a success both in the U.S. and Europe. His popular book was largely responsible for changing views towards the environment, spurring the start of the conservationist movement. He also became one of the founders of an organization that eventually became known as “Boy Scouts of America.” Today, Lobo’s pelt is displayed at the Seton Memorial Museum-Libry at Philmont Scout Ranch in Cimarron, New Mexico.

©Matt Doherty for Legends of America, submitted February 2024.

About the Author: Matt Doherty is a seventh-generation rancher from the Folsom area of New Mexico. Doherty’s family also owns the Doherty Mercantile building, which houses the Folsom Museum, where he sits on the board of directors. Visit Folsom

Also see:

Rayado, New Mexico – On the Santa Fe Trail

Dry Cimarron Scenic Byway, New Mexico

Folsom, New Mexico – High Plains Ghost Town

John R. Abernathy – Wolf Catcher & Lawman