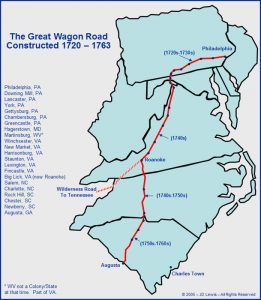

The heavily traveled Great Wagon Road, also called the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road, was the primary route for the early settlement of the Southern United States.

Stretching for 800 miles, the road began in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, crossed westward to Gettysburg, turned south to Hagerstown, Maryland, and entered the Shenandoah Valley near present-day Martinsburg, West Virginia. The path then continued south to Winchester, Virginia, through the 200-mile length of the Shenandoah Valley to Roanoke. Through here, the road was known as the Valley Pike and followed the earlier established Great Warrior’s Trail. The Wilderness Road branched off from the Great Wagon Road at Roanoke and crossed through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky and Tennessee. The road then passed through the Roanoke River Gap to the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains into North Carolina. Here, it was called the Carolina Road. It then continued south to Rock Hill, South Carolina, which branched into two routes to Augusta and Savannah, Georgia.

In the beginning, packhorse trains transported goods along old Indian trails that would later become known as The Great Wagon Road. In the mid-1700s, European colonists, who had arrived on ships in or near Philadelphia, began traveling south along the trail, searching for land to build their homes.

At first, the road was so narrow and rough that only travelers on horseback could use it, and the further south they traveled, the more impassable it became. Although traffic on the road increased dramatically after 1744, it was reduced to a trickle during the French and Indian War from 1756 to 1763. But after the war ended, it was said to be the most heavily traveled main road in America.

Little by little, as settlers made their way along the trail, they cut trees, found suitable fords across rivers, and worked around obstacles. By 1765, the trail had been widened and improved enough to allow the passage of horse-drawn vehicles. Before long, large freight wagons known as Conestoga wagons carried manufactured goods to the frontier and returned loaded with trade goods like animal pelts. In the summer, the road was crowded with drovers leading their livestock to market.

Even though the road had been much improved, travel was still slow and arduous, and for many years, an ax, a pick, and a shovel were necessary tools for anyone traveling the road. The road would frequently be washed out by rain or be blocked by fallen limbs or trees. When surveying the Road as Postmaster, Benjamin Franklin injured his arm when he fell from a wagon and bounced through a series of deep ruts.

The Great Wagon Road was the key supply line to the American resistance during the American Revolution, especially in the South.

By the 1790s, numerous towns had been established along the Great Wagon Road, and by the early 1800s, county courts appointed overseers responsible for keeping up with the various road segments.

The road continued to play a significant economic role into the 19th century when the expansion of railroads and the development of new roads occurred. It fell into disuse and, in many areas, disappeared.

Much of the original route remains in Maryland and Virginia as State Highway 11. Parts of the old road can be found in heavily wooded tracts, and often, local roads follow a brief stretch of the old route.

© Kathy Alexander-Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

National Road – First Highway in America

Tales & Trails of the American Frontier

The Wilderness Road Opens Kentucky

Sources: