The San José de los Jémez Mission and Gíusewa Pueblo Site in Sandoval County, New Mexico, includes the remains of an early 17th-century mission complex and a Jémez Indian pueblo importantly associated with the Spanish colonial and Native American history of the area.

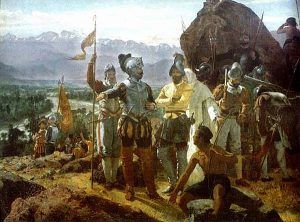

After the first Spanish explorers and conquistadors swept through New Mexico in the 16th century, Spain sent Franciscan friars to settle the land and convert the Pueblo nations to Catholicism.

New Mexico’s Pueblo peoples, including the Jémez, were first contacted by the Spanish in 1541 when explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado led a large expedition through New Mexico. After that first contact, 40 years passed until another European expedition, led by Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado and Fray Agustín Rodríguez, briefly visited the Gíusewa Pueblo in 1581. “Gíusewa” is a Towa word that in English means “place at boiling water” because the pueblo is located near a thermal spring.

The Jémez people are a Towa-speaking people who migrated to the Cañon de San Diego Region from the Four Corners area in the late 13th century. By the time of European contact, the Jémez Nation occupied numerous villages strategically located on the high mountain mesas and in the canyons surrounding the present pueblo of Walatowa, about 12 miles south of the old Gíusewa Pueblo. This pueblo was established in about 1450-1500

Spanish missionaries first settled at the Gíusewa Pueblo in 1598 when Don Juan de Oñate, the first governor of New Mexico, colonized the province and brought five friars and 400 soldiers, colonists, and slaves with him. After Oñate’s government formed a capital at San Gabriel de Yunque-Ouinge, one of the Franciscans, Fray Alonso de Lugo, moved to Gíusewa to establish a Jémez mission province in the narrow San Diego Canyon. Father Lugo built a small convento and church, but he only lived at Gíusewa for three years. In 1601, Lugo and most of the other Franciscan missionaries left New Mexico, perhaps in protest of Oñate’s violent and authoritarian approach to dealing with the Pueblo peoples.

In 1621, the Franciscans returned to the Jémez when Gerónimo de Zárate Salmerón, a Mexican priest of Spanish descent, moved to Gíusewa to build a large mission church and to continue converting the Jémez to Catholicism. Unlike many other friars, Zárate Salmerón had a background in architecture. Before leaving Mexico City, Zárate Salmerón designed and oversaw the construction of at least two large causeways at Ecatepec and Xochimilco near Mexico City. From 1621-1623, Zárate Salmerón planned and managed a major project to construct a large church near the pueblo that incorporated Fray Lugo’s small convento and church buildings. The Jémez residents built the mission buildings according to traditional Pueblo practice. Jémez women constructed the massive church walls by laying the cut yellow limestone and spreading plaster. Jémez men cut, carved, and placed wooden beams, intricate interior woodwork, and crosspieces. The church was unusual for its massive size and rare, octagonal bell tower. In 1630, Fray Alonso de Benavides of New Mexico wrote that the San José de los Jémez Mission at Gíusewa Pueblo was a “breathtaking, sumptuous, and distinguished church and friary.”

The Spanish government supported the colonizing efforts of Franciscan missionaries by providing them with material resources and soldiers. Throughout the 17th century, wagon caravans carried candles, bronze bells, musical instruments, medicines, clothing, European foods, and iron tools from Mexico City north to New Mexico’s missions. Spain also sent tools and hardware to every New Mexican friar who wanted to construct a mission church. Throughout the region, the Pueblo neophytes used both European and indigenous tools to build mission infrastructure under the missionaries’ direction.

Officially, Spain’s primary mission in the Americas was to convert the indigenous populations to Catholicism and “civilize” them through European culture. Members of the Franciscan religious order that Saint Francis of Assisi founded often traveled with Spanish conquistadors and colonizers to spread Christianity and supervise acculturation. In populated areas, a Franciscan missionary would move in and try to establish a mission where he could teach indigenous residents Spanish culture, language, and religion. In the early years of a mission, the priests focused their conversion efforts on the youth, especially younger native leaders, who they believed were easier to influence than their elders. The early Pueblo converts may not have given up their traditional beliefs but thought of conversion as adding Christian saints to their own traditions. However, once in power, the Spanish ordered the destruction of all non-Christian religious or spiritual imagery and objects and outlawed Pueblo religious expression. The priests also restructured Pueblo society by combining smaller villages into larger settlements like Gíusewa, which housed 500 to 800 residents. The Spanish did this to keep the Pueblo under the control of a limited number of priests and manage the shrinking Pueblo population that decreased steadily throughout the 17th century from war, famine, and disease.

Intertribal attacks, the repression of native culture, and dissatisfaction with Spanish leadership led the Pueblo to stage a highly coordinated revolt against the Spanish in 1680. The Jémez participated in the revolt, killing a Franciscan in their province and working with the other Pueblo groups to force the Spanish out of New Mexico. Popé, a Pueblo man of San Juan de Ohkay Owingeh, led the revolt. The Pueblo first removed the Spanish from power in their own villages and then assaulted the capital at Santa Fe, where 2,500 Pueblos drove all of the Spanish colonists out of the city and forced them out of the province of New Mexico. The Spanish returned and recolonized New Mexico 12 years later, but the Jémez continued to war with the Spanish until 1696. After suffering a heavy defeat, the Jémez survivors abandoned their villages, and some of them joined neighboring pueblos of the Acoma, Zuni, Laguna, and Hopi. By 1706, the Spanish forced the remaining Jémez to move to Walatowa, which is about 12 miles south of Gíusewa Pueblo and is the site of modern Jémez Pueblo that is home to the Jémez Nation today.

The San José Mission and Gíusewa Pueblo site fell into ruins after the Spanish and Jémez deserted it in the late 1600s. In 1849, members of the United States Topographical Corps rediscovered Gíusewa Pueblo during a land survey. In the latter decades of the century, farmers and ranchers occupied the abandoned San José convent. Soon, tourists, scholars, and photographers began to visit the ruins. The first excavation of San José de los Jémez took place in 1910, and excavations continued sporadically throughout the 20th century. Private landowners donated the land that contains San José and Gíusewa to the Museum of New Mexico and the School of American Research in 1921, and the State of New Mexico turned the property into a State monument in 1935. In the Jémez State Monument’s land, believed to contain only 20 percent of the original Gíusewa Pueblo, archeologists excavated 62 of approximately 200 ground floor rooms, three Pueblo kivas (underground ceremonial rooms), and two plazas. Spanish and Pueblo artifacts recovered from the site are deposited at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe.

Jémez State Monument, a unit of the Museum of New Mexico, is an hour and a half drive north of Albuquerque and west of Santa Fe. A visitor center at the monument entrance exhibits Pueblo artifacts and provides information about Jémez history. After completion, the massive San José church’s ruins, which rose to 39 feet tall at its top parapet after completion, stand out among the surrounding pueblo ruins. A paved trail, lined with information panels, weaves through the excavated mission and pueblo site.

The San José de los Jémez Mission and Gíusewa Pueblo Site was designated a National Historic Landmark on October 16, 2012.

The historic mission and Pueblo are located on State Highway 4, 43 miles north of Bernalillo, New Mexico. It is open Wednesday through Sunday for a nominal fee.

More Information:

San José de los Jémez Mission and Gíusewa Pueblo

18160 New Mexico State Highway 4

575-829-3530

Compiled by Kathy Alexander, updated April 2021.

Also See:

Ancient & Modern Pueblos – Oldest Cities in the U.S.

Pueblo Indians – Oldest Culture in the U.S.

Puebloan People Photo Galleries

Spanish Missions in New Mexico

Sources:

National Historic Landmark Nomination

National Park Service

New Mexico Historic Sites