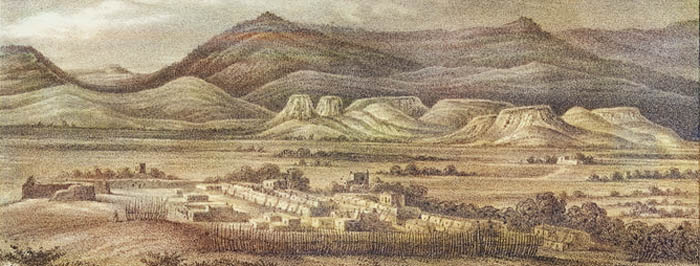

The Jemez Pueblo in north-central New Mexico is the last remaining pueblo of the Towa-speaking people.

The Jemez, pronounced “Hay-mess,” originated from a place they called “Hua-na-tota” in the area of Largo Canyon in northwestern New Mexico. After having lived there for at least 1,000 years, the people migrated south in the 14th century to the southwestern Jemez Mountains in north-central New Mexico. The Jemez people were primarily farmers but were also hunter-gatherers.

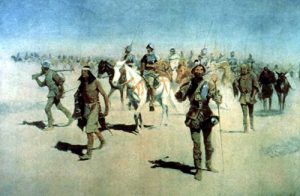

Coronado’s Expedition by Frederic Remington

The Jemez were first encountered by Europeans when Spanish Conquistador Francisco Vazquez de Coronado’s expedition, including 500 soldiers and 2,000 Indian allies from New Spain, came to the area in 1541. At that time, the Jemez Nation was one of the largest and most powerful of the Puebloan cultures, occupying more than 40 villages strategically located on the high mountain mesas and the canyons surrounding the present-day pueblo of Walatowa. Many villages comprised more than 500 rooms with hundreds of small one to two-room field houses. These stone-built fortresses, often located miles apart, were four stories high, and a few contained as many as 3,000 rooms. The Spanish documented 11 Jemez villages in their reports.

Situated between these “giant pueblos” were hundreds of smaller one and two-room houses that the Jemez people used during spring and summer as basecamps for hunting, gathering, and agricultural activities. However, the spiritual leaders, medicine people, war chiefs, craftsmen, pregnant women, the elderly, and the disabled lived in the giant pueblo throughout the year.

For protection, warriors were located nearby, and impenetrable barriers were established among the cliffs to guard access to springs and religious sites, monitor trail systems, and watch for invading enemies. Resembling a military society, the Jemez were often called upon by other tribal groups to assist in settling hostile disputes.

Searching for the fabled Seven Cities of Gold, Coronado and his men didn’t take any aggressive action against the pueblo, perhaps because it was so large.

Forty years after Coronado arrived, the Rodriquez-Chamuscado Expedition entered the area in 1581, followed by the Espejo Expedition in 1583. At that time, the Jemez nation contained an estimated 30,000 tribal members living throughout San Diego Canyon.

In 1598, Don Juan de Onate claimed New Mexico for the Spanish crown as a province of New Spain. Soon, a detachment of the first colonized expedition visited the Jemez, and a Franciscan priest, Father Alonzo de Lugo, was assigned to missionize the Province of Jemez. At that time, the villages were consolidated into the three pueblos of Astialakawa, Patoqua, and Giusewa. Giusewa, meaning the “place of boiling waters” in Towa, was about nearby hot springs. It was the largest of the three ancestral villages of the Jemez Pueblo, having an estimated 500-800 people. It consisted of about 350 small square rooms made of volcanic tuff masonry and adobe, with flat earthen roofs. These were terraced to form room blocks of two to three stories that clustered around several square plazas.

Fray Alonzo de Lugo had the Jemez build the area’s first church at the Jemez Pueblo of Guisewa. Father Lugo built a small convento and church but only lived at Gíusewa for three years. In 1601, Lugo and most other Franciscan missionaries left New Mexico, perhaps in protest of Oñate’s violent and authoritarian approach to dealing with the Pueblo peoples. By 1610, the mission had been abandoned, and the Jemez had scattered to fortified pueblos on high, inaccessible mesas.

In about 1621, Fray Gerónimo de Zárate Salmerón was assigned as the next missionary of Jemez. Hoping to gather and convert the dispersed population, Salmerón began constructing the large mission church of San José de Giusewa in 1621-1622. Around 1623-1625, the church was damaged by a fire in a Navajo raid. Afterward, the Jemez again fled into the mountains.

This “forced” conversion was not easy, prompting Fray Alonso Benavides to say in 1926 that the site was “one of the most indomitable and belligerent of the whole kingdom.”

However, the Spanish continued to try and, in 1628, sent Fray Martin de Arvide. This priest finished rebuilding the mission, and as part of the ongoing attempt to consolidate the Jemez, Arvide established a second mission at Walatowa, located 13 miles south of Giusewa at the present site of Jemez Pueblo. In 1632, Arvide was transferred to Zuni, where he was killed.

In the following years, the Jemez remained at Walatowa and continued to resist the attempts of Christianization by subsequent friars assigned to the mission at Giusewa. Today, the Giusewa church ruins and village comprise the historic Jemez State Monument located on State Highway 4 in Jemez Springs, New Mexico.

By 1680, the hostilities resulted in the Great Pueblo Revolt, during which the Spanish were expelled from New Mexico through the strategic and collaborative efforts of all the Puebloan Nations. This was the first and only successful revolt in the United States in which a suppressive nation was expelled. Unfortunately, these wartime efforts and diseases introduced by the Europeans decimated the population of the Jemez.

By 1688, the Spanish had begun to reconquer New Mexico under the leadership of General Pedro Reneros de Posada, acting Governor of New Mexico. The Pueblos of Santa Ana and Zia were first conquered, and by 1692, Santa Fe was again in Spanish hands under Governor Diego de Vargas.

In the meantime, the Jemez fled to a mesa between the San Diego and Guadalupe Canyons. From here, they invaded the pro-Spanish Pueblos of Zia and Santa Ana in 1693. In July 1694, de Vargas led an attack on the Jemez in which 84 men were killed, and 361 women and children were captured and taken to Santa Fe. The captives were returned to Walatowa in 1695 and were instructed to build a new mission church under Fray Francisco de Jesús. The new church’s construction, first dedicated to San Juan de los Jemez, was abandoned, however, when Jemez warrior Luis Cunixu killed Fray Jesús in 1696. Many of the Jemez again fled to the mountains though many returned within a few years.

However, the Jemez Nation remained under clergy and military rule. At that time, the people were forced to move to the Village of Walatowa. This time, however, the Spanish did not persecute their culture and traditions to the extent they had previously, which enabled them to preserve many parts of their way of life. It would eventually lead to many significant ancestral sites outside the Pueblo, which are now on federal lands and no longer controlled by the Jemez. These sites now constitute some of the most significant archaeological ruins in the United States.

By 1706, construction of the church at Walatowa had resumed. Now dedicated to San Diego, Apache raiders destroyed the church in 1709. However, it was subsequently rebuilt and was a fully functioning mission by 1744.

When Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez visited Walatowa and described it:

“It all stands behind the church and convent, extending to the north. It consists of five blocks, or tenements, all of adobe, and two of them stand at the ends, one on the east and the other on the west because the other three run across between them, one behind the other… and there are very good streets between them.”

In 1838, survivors of Pecos Pueblo, a once-mighty trading center now in ruins, joined the Jemez. At that time, the Towa-speaking people from Pecos, located east of Santa Fe, resettled at the Pueblo of Jemez to escape the Spanish and Comanche cultures’ increasing depredations. Readily welcomed, the Pecos culture was rapidly integrated into the Jemez Society. Nearly a century later, in 1936, the Jemez and Pecos people were legally merged into one by an Act of Congress.

In the second half of the 20th century, many Jemez people switched to wage-earning work rather than agriculture. However, pueblo residents continue to raise chili peppers, corn, and wheat. They are also internationally known for arts and crafts, including pottery such as elaborately polished and engraved bowls, wedding vases, figurines, beautiful basketry, embroidery, woven cloths, exquisite stone sculpture, moccasins, and jewelry.

Today, the Jemez is a federally recognized tribe with about 3,400 members, most of whom reside in the Puebloan village of Walatowa. One of the 19 remaining pueblos of New Mexico, the tribe’s land encompasses over 89,000 acres surrounded by colorful red sandstone mesas.

This is the gateway to the Cañon de San Diego and the Jémez Mountain Trail National Scenic Byway. Nearby is Jemez Red Rocks Recreation Area, Jemez Springs, and Jemez State Monument.

The Pueblo of Jemez is an independent sovereign nation with an independent government and tribal court system. The Tribal Government includes the Tribal Council, the Jemez Governor, two Lieutenant Governors, two fiscales (government revenue officers,) and a sheriff. The second Lieutenant Governor is also the governor of the Pueblo of Pecos. Traditional matters are handled through a separate governing body rooted in prehistory, including spiritual and society leaders, a War Captain, and Lieutenant War Captain.

The Jemez have retained their cultural traditions and practices unchanged since Pre-Spanish times. These include the culture and traditions of the Pecos Pueblo. The Jemez people also continue to speak the Towa language. The community remains agriculturally self-sufficient, and many residences maintain small gardens for the cultivation of native vegetables: beans, corn, chile, and squash.

The pueblo itself is closed to the public except during feast days. Traditional dances are held throughout the year at Jemez. The public is welcome at the “Nuestra Senora de Los Angelas Feast Day de Los Persingula,” held on August 2nd, and the “San Diego Feast Day” on November 12th. Additional events open to the public occur at various times throughout the Christmas Holidays.

Walatowa, the main village, is open to the public. The Pueblo of Jemez-Walatowa Visitor Center and Museum of History and Culture is located at 7413 Hwy 4, Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico. A reconstructed traditional Jémez field house, photo exhibit, gift shop, cultural exhibits, a nature walk, and an interpretive program can be seen here.

The Jemez Pueblo is located 27 miles northwest of Bernalillo on New Mexico Highway 44 within the southern end of the majestic San Diego Canyon.

More Information:

Pueblo of Jemez

7413 New Mexico Highway 4

P.O. Box 280

Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico 87024

575-834-7235

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated September 2022.

Also See:

Ancient & Modern Pueblos – Oldest Cities in the U.S.

Pueblo Indians – Oldest Culture in the U.S.

Puebloan People Photo Galleries

San José de los Jémez Mission and Gíusewa Pueblo, New Mexico

Spanish Missions in New Mexico

Sources:

The Local Tourist

MarlonMagdalena

New Mexico True

Pueblo of Jemez

Society of Architectural Historians