1928 Interior view of the old Bank of Telluride, Colorado. Charles (Buck) Waggoner (left) and Mr. Skanland advertise their bank’s stability with stacks of silver dollars protected by handguns on the counter. Source – Denver Public Library Special Collections.

By Daniel R. Seligman

Among the outlaws of the American West, one has to look long and hard for a true Robin Hood — someone who actually robbed from the rich for the benefit of the poor. To be sure, there were a number of reputed Robin Hoods, often motivated by factors beyond mere personal profit, but, upon close examination, they usually fall short of the standards allegedly set long ago in Sherwood Forest.

Jesse James garnered a good deal of sympathy in his native Missouri by his passionate support for the Confederate cause long after the Civil War was over. His victims were primarily banks and railroads, unpopular symbols of Yankee industrialization, and he usually took pains to avoid stealing from Confederate sympathizers. But he appears to have kept his ill-gotten gains for the benefit of himself, his gang and his family.

Charles Bolton, a.k.a. Black Bart, California stagecoach robber par excellence, avoided robbing passengers, focusing exclusively on the US Mail and the Wells Fargo express boxes. And he was scrupulously polite, especially to ladies. But he seems to have employed his proceeds entirely in bankrolling his alternate lifestyle as a San Francisco gentleman, even to the point of depriving his struggling and abandoned family.

Butch Cassidy comes a little closer. Like Jesse James, he robbed banks and railroads, but, unlike James, was generous with the proceeds of his crimes. In a characteristic incident, his Wild Bunch, in a celebratory mood, shot up Jack Ryan’s Bull Dog Saloon in Baggs, Wyoming, putting 25 bullet holes in the bar….and then paid the owner for the damages at the princely rate of one silver dollar per hole. While this sort of behavior made him popular with the locals – despite the damage – it doesn’t exactly rise to the level of robbing the rich for the benefit of the poor.

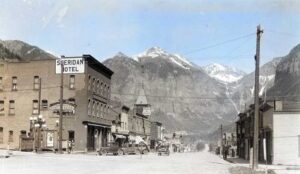

A true Robin Hood did, eventually emerge, however, in the unlikely person of Charles Delos Waggoner, a banker in Telluride, Colorado, interestingly — and perhaps appropriately — the same town where Cassidy pulled off his first bank robbery in 1889 (though not the same bank). His weapon of choice was neither an English longbow nor a Colt .45, but rather an expert understanding of banking laws and conventions and a ruthless determination to exploit his knowledge for the benefit of his depositors.

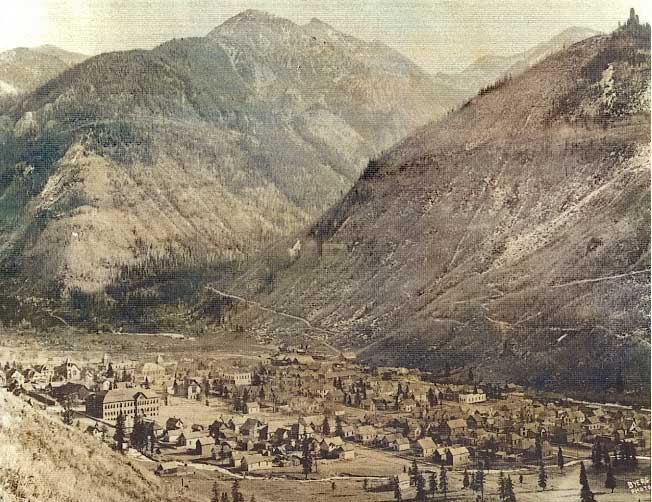

Telluride, Colorado after the turn of the 20th Century.

Waggoner came to Telluride in 1896 where he was employed by the Bank of Telluride as a bookkeeper. In 1907 he was promoted to cashier and, in 1919, bank president. In the late summer of 1929 it became obvious to him that his bank was on the verge of failure and he determined that, whatever the cost to himself, he was going to protect his depositors.

Waggoner planned his scam down to the last detail. On August 30 he had telegrams encoded with a confidential bankers’ code sent to each of six New York banks — National City Bank, First National Bank, Harriman National Bank and Trust Company, Chemical Bank and Trust Company, Equitable Trust Company and Guaranty Trust Company — supposedly from their correspondents in Denver, instructing them to transfer a total of $500,000 to the account of the Bank of Telluride at the Chase National Bank. The following day, he showed up personally in New York to draw certified checks on the balance. He then proceeded to use the purloined funds to pay off the obligations of the Bank of Telluride, thereby protecting his depositors from losing their savings in the bank’s imminent collapse. And the banking transactions were backed by certified checks, making it difficult or impossible for the affected banks to recover the money. $500,000 in 1929 would be worth roughly $8.5 million in 2022.

The fraud was not discovered until the New York banks acknowledged execution of the orders to their Denver correspondents who, of course, claimed no knowledge of the transactions. On September 10, Waggoner was arrested at a tourist resort outside Newcastle, Wyoming, having made no serious effort to elude capture. He was arraigned in New York on six federal counts of using the mail to defraud with bail set at $100,000 – money which he didn’t have and so he remained in custody.

On his way to New York to stand trial, Waggoner passed through Chicago where he told the New York Times:

I think I am going to jail for the rest of my life but I can honestly say that I am not the least bit worried. My mind is free because I know that I have saved thousands of working people who trusted in me and who had deposited every penny that they could save up in my bank. Eighty percent of them were paid off before this happened. What they do to me now doesn’t matter much except, of course, that it is going to make my wife, my son and my friends feel badly for me.

The trial had its share of petty difficulties. Upon arrival in New York, Waggoner, while still in the custody of US Deputy Marshalls from Wyoming, made a side trip to provide an interview to a newspaper, holding up the court for an hour to the consternation of US Attorney Tuttle. And witnesses brought in from Colorado complained that they were having difficulty living in New York on the pitiful allowance of $5 per day.

Waggoner admitted sending the telegrams and took sole responsibility for the financial manipulations. He was sentenced to 10 years in the Atlanta Penitentiary, with Judge Coleman and US Attorney Tuttle both recommending to the parole board that he actually serve at least 5 years. He began serving his sentence in November.

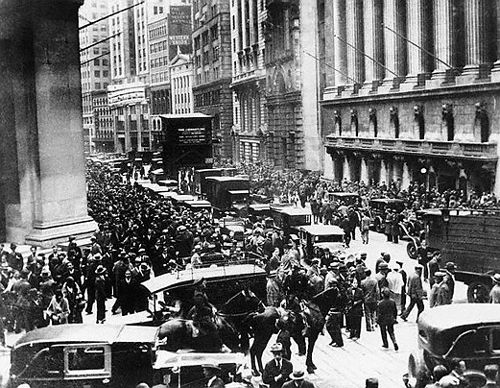

Black Tuesday on Wall Street, New York City

Perhaps fittingly, Waggoner’s crime, apprehension, and trial took place in the shadow of the stock market crash of October 24-29, 1929, which precipitated the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Waggoner was paroled in May, 1935. A convicted felon during the Depression, he had difficulty finding work, so he contacted an old friend, J. Walter Eames, who operated the Biltmore Club in Grand Junction, Colorado. By some accounts, Eames owed Waggoner a favor, Waggoner having bankrolled a destitute Eames with $300 in gold some years earlier. Eames employed him either in the office or operating a gaming table. A few years later, Waggoner received unwelcome publicity as a side effect of a murder investigation when, on December 18, 1938, three masked gunmen attempted to rob the club and managed to kill Eames with a sawed-off shotgun. In 1939 Waggoner and his wife moved to Reno, Nevada, where he found employment selling brushes. She died in 1957 and he in 1960 at age 87.

Waggoner has all the makings of a true Robin Hood figure. He literally robbed from the rich, in this case the New York banks, for the benefit of the less fortunate, the depositors in the local Bank of Telluride. He in no way profited from his crime. It was done solely for the benefit of his depositors — farmers, ranchers, miners and local businessmen – and he spent several years in prison for his pains. Whether Waggoner was a “cold-blooded rascal,” as claimed by US Attorney Tuttle, or a self-sacrificing altruist is a judgment best left to the reader.

Today a plaque on the exterior wall of the Bank of Telluride building, 109 West Colorado Avenue, commemorates Charles D. Waggoner and “The Great Waggoner Swindle.”

©Daniel R. Seligman, for Legends Of America, submitted November 2022.

Author Daniel R. Seligman

About the Author: Daniel is a retired computer engineer from Massachusetts with a lifelong interest in the American West. He teaches seminars on western gunslingers and has authored a number of articles on western history in various publications, including:

Going for Gold: How the Confederacy Hatched an Audacious Plan to Finance Their War, America’s Civil War, July 28, 2022

Tracking the White Apache, Wild West, October 2021, 44-49

King of the Tulares, Wild West, April 2021, 58-63

Annie Oakley’s Gaffe…Or Was It?, Wild West History Association Journal, September 2019, 69-73

Rough and Ready, Wild West, October 2019, 44-49

Bound and Determined, Wild West, August 2018, 46-51

This Scout Lived with the Enemy, Wild West, August 2018, 22-23

Western Stagecoach Robberies: A Statistical Analysis, Wild West History Association Journal, December 2017, 23-27

Evolution of a Mountain Man, Wild West, October 2017, 58-63

The Greatest of Confidence Men, True West, June 2015, 40-41

The Flawed Gentleman Bandit, True West, December 2013, 32-35

Frank Butler, Much Maligned Husband, True West, March 2013, 44

Sources:

“Charles Waggoner Dies in Reno, Nevada,” San Miguel Basin Forum, July 21, 1960

New York Times, dates in 1929: Sep 07, 08, 09, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28; Oct 03, 05, 09, 12, 19, 29; Nov 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21; Dec 01

“Robin Hood of Telluride Lived Quietly in GJ,” Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, April 30, 2010

Town of Telluride, Colorado Cultural Resource Survey, Architectural Inventory Form, 109 W Colorado Ave

US Bureau of Labor Statistics, CPI Inflation Calculator

“Waggoner’s Gesture,” Time Magazine, Sep 16, 1929

Wilson Rockwell, Sunset Slope, 1956, 1999, Chapter XIII

Betty Zatterstrom, “The Robin Hood Banker of Telluride,” San Miguel Basin Forum, May 25, 1989

Betty Zatterstrom, “Robin Hood Banker – Part II,” San Miguel Basin Forum, June 1, 1989

More by Daniel Seligman:

Scouts of the Prairie: A Glorious Disaster

Mary Jane Simpson – The Lady and the Mule

Also See:

Scoundrels Across American History