The Camp Jackson Affair, also known as the Camp Jackson Massacre, occurred on May 10, 1861, during the Civil War.

Less than a month after the war’s first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, the first instance of bloodshed in Missouri occurred when a volunteer Union Army regiment captured a unit of secessionists at Camp Jackson outside the city of St. Louis.

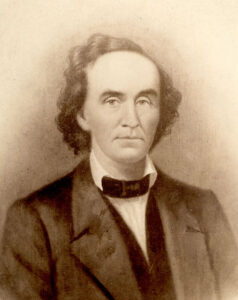

Missouri was very divided in the early days of the war. Through slavery and commerce down the Mississippi River, the state had ties to states that would become a part of the Confederacy. Through industrialization, railroad trade, and immigration, the state also had ties to the North. Newly elected Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson was sympathetic to the Confederacy and called for a state constitutional convention to debate the merits of secession in February 1861. On March 21, the Convention voted 98 to 1 against secession but also voted not to supply weapons or men to either side if war broke out. The Convention then adjourned. Afterward, Governor Jackson and his allies still maneuvered for Missouri’s secession using questionable methods.

Jackson refused President Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops after the firing of Fort Sumter. With approval from the state legislature, he began raising and equipping the Missouri State Guard, a state militia whose members were primarily secessionist.

On April 20, several days after the Battle of Fort Sumter, a pro-Confederate mob seized the Liberty Arsenal in Liberty, Missouri, and confiscated about a 1,000 rifles and muskets. This sparked fears that Confederates would also seize the much larger St. Louis Arsenal, which had nearly 40,000 rifles and muskets — the largest stockpile in any slave state.

Confederate forces had overtaken other federal arsenals in the South, so the threat to the St. Louis federal arsenal was credible. Moreover, Jackson supported a bill that placed the St. Louis City Police under state control, weakening the protection of the arsenal. Soon the Missouri State Guard established an encampment just west of downtown St. Louis which they named after their governor, Camp Jackson.

General William Harney was a conservative commander in charge of federal troops in St. Louis. Underneath him was Captain Nathaniel Lyon, who was tasked with defending the arsenal alongside Frank Blair, an influential U.S. Congressman from St. Louis. They began raising their own pro-Union militia, comprised of many German immigrants, and through Blair’s influence, became sanctioned by the Lincoln administration. In St. Louis, to help with mustering troops in nearby Belleville, Illinois, Captain Ulysses S. Grant wrote to his wife Julia about this development:

“There are two armies now occupying the city, hostile to each other, and I fear there is great danger of a conflict which, if commenced, must terminate in great bloodshed and destruction of property without advancing the cause of either party.”

To safeguard surplus weapons at the arsenal, Lyon shipped them across to Illinois for safekeeping.

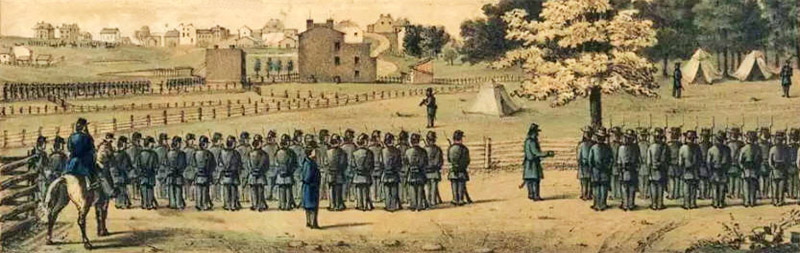

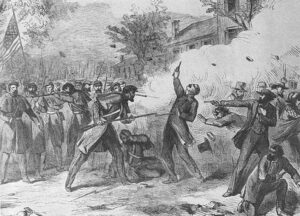

Grant was correct about the inevitable clash. To prevent the pro-secessionist militia from storming the arsenal, and after hearing that Camp Jackson had received four cannons captured by Confederates at the Federal Arsenal at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Lyon and Blair led a preemptive march on May 10, with 6,500 troops to force Camp Jackson’s 700-man garrison to surrender. Before the march started, Grant had gone to the arsenal and personally chatted with Lyon and Blair, expressing sympathy for their purpose. The march was successful, and the garrison at Camp Jackson surrendered. But as Grant predicted, violence occurred when Lyon marched his prisoners through the streets of St. Louis. Many people St. Louis residents came out to witness this procession. Among the spectators was a mob of secessionists who were incensed that a great number of the Unionist militia was German. They first began heckling the Unionists and shouting ethnic slurs. It then turned violent when the secessionists brandished knives and guns and threw objects at the Unionist troops. After an accidental gunshot, Lyon’s men fired into the mob, killing at least 28 civilians, including women and children, and injuring dozens of others.

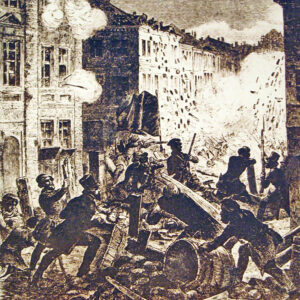

Several days of rioting throughout St. Louis followed. The violence ended only after martial law was imposed and Union regulars were dispatched to the city.

Afterward, sporadic violence continued for another day, with six more deaths. During this time, Grant, intending to return to the arsenal to congratulate Lyon and Blair, witnessed the commotion. He later reflected in his memoirs that he encountered and had a conversation with a St. Louis secessionist. When the secessionist bluntly told him, “Where I come from, if a man dares to say a word in favor of the Union, we hang him to a limb of the first tree we come to.” Grant retorted, “After all, we are not so intolerant in St. Louis as we might be; I had not seen a single rebel hung yet, nor heard of one; there were plenty of them who ought to be, however.”

Following the Camp Jackson Affair, General Harney struggled to keep the peace between secessionist and unionist elements in Missouri. On May 21, Harney met with Confederate General Sterling Price, a former governor of Missouri. They worked out an agreement in which Price’s state forces kept order in Missouri, and the federal government would not interfere in state affairs, but the federal army would regulate affairs in St. Louis. By this agreement, General Harney conceded to the heavily pro-secessionist state authorities the right to run state affairs. Naturally, Frank Blair, Nathaniel Lyon, and their allies were incensed by this, and they successfully maneuvered for Harney’s removal and for Lyon to replace him.

Soon after, Lyon was promoted to Brigadier General. He bluntly stated his uncompromising unionist stance in a meeting with Claiborne Fox Jackson, Sterling Price, and Frank Blair at the Planters House in St. Louis. When Price sought to continue the agreement that he worked out with Harney, Lyon would hear none of it. Irritated and uncompromising, Lyon allegedly stood up during the middle of the meeting and stated angrily, “Rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any matter however unimportant… I would see you and every man, woman, and child in the State, dead and buried.” As he finished, he turned to Governor Jackson with the grand finale of his speech, “This means war.” From that moment, the Civil War was officially underway in Missouri.

In the meantime, Governor Jackson returned to the state capital at Jefferson City. Lyon delivered federal troops by steamboat to Jefferson City on June 12, and Jackson fled west to join newly assembled State Guard troops near Boonville. Lyon’s men occupied the capital without resistance and pursued Jackson with approximately 1,400 volunteers and U.S. Army regulars. Against the advice of his senior officers, Jackson exercised his authority as Commander-in-Chief and ordered the State Guard to make a stand at Boonville. In the resulting Battle of Boonville on June 17, Lyon’s troops routed the State Guard. Jackson, the State Guard, and a few secessionist state legislators escaped to southwest Missouri, near the Arkansas border, leaving most of the state under federal control.

A Missouri Constitutional Convention convened on July 22 and declared the office of Governor vacant due to Jackson’s absence. The Convention then voted to appoint former Chief Justice of the Missouri Supreme Court and conservative Unionist Hamilton Rowan Gamble as Governor of the Provisional Government of Missouri.

Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon would not see the fruition of his uncompromising Unionist stance, dying at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek near Springfield, Missouri, on August 10, 1861. Ulysses S. Grant remembered the Camp Jackson Affair and praised Lyon and Blair in his Personal Memoirs.

“I have little doubt that St. Louis would have gone into rebel hands, and with it the arsenal with all its arms and ammunition” had Lyon and Blair allowed Camp Jackson to stand. “As soon as the news of the capture of Camp Jackson reached the city, the condition of affairs was changed. Union men became rampant, aggressive, and, if you will, intolerant. They proclaimed their sentiments boldly and were impatient at anything like disrespect for the Union.”

In the meantime, former Governor Jackson took refuge in Arkansas with Confederate General Sterling Price and the Missouri Militia. He was in Arkansas again on December 6, 1862, when he died from pneumonia at age 56 in a Little Rock rooming house.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, June 2023.

Also See:

Civil War Timeline & Leading Events

Sources: