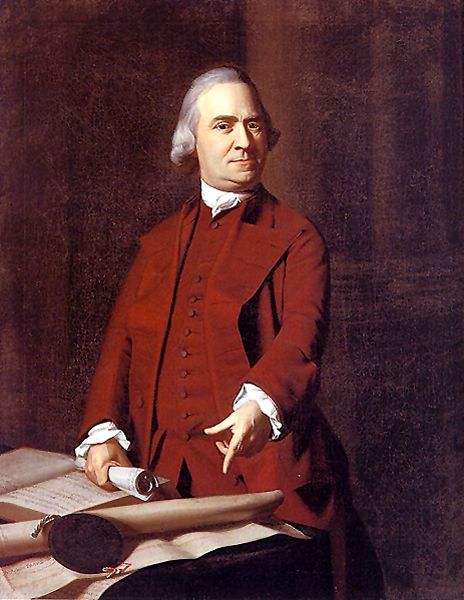

Samuel Adams

While the people of Virginia, under the leadership of Patrick Henry, arose against King George’s Stamp Act, they were not alone in their opposition to the English King. Just as brave and liberty-loving were the Massachusetts people, with Samuel Adams as their leader.

Samuel Adams was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on September 27, 1722, to Samuel Adams, Sr., and Mary Fifield Adams. Though he was one of 12 children born to the couple, only he and two others would live beyond three years. Adams’s parents were devout Puritans and the Old South Congregational Church members. His father was a prosperous merchant and church deacon who became a leading figure in Boston politics.

Little is known of Samuel Adams’s boyhood; however, he appeared to have been an academic, in-door sort of boy with little fondness for sports. He attended Boston Latin School during his youth and entered Harvard College in 1736. After graduating in 1740, Adams continued his studies, earning a master’s degree in 1743. After leaving Harvard, his parents hoped he would become a minister. However, Samuel was more interested in studying law. His mother disapproved, so he moved on to business, eventually joining his father in the malt business. But, Adams’ real passion was politics, and he showed little interest in making money.

In January 1748, he and several friends launched the Independent Advertiser, inflamed by British impressment (forcibly inducting men into military service). This weekly newspaper printed many political essays written by Adams. These early writings emphasized many themes that would characterize his subsequent career. That same year, his father died, and Adams took over the management of the family’s affairs. In October 1749, he married Elizabeth Checkley, and the couple would eventually have six children, only two of whom would live to adulthood.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Adams embarked upon a political career. After serving as a clerk in the Boston market, he was elected tax collector in 1756, providing a small income. Because he often failed to collect taxes from his fellow citizens, he “failed” in his duties, becoming liable for the shortage. But, he was popular with the people, who helped pay off the debt, and Adams emerged as a popular party leader.

In July 1757, Samuel’s wife Elizabeth died soon after giving birth to a stillborn son. Several years later, he would remarry in 1764 to Elizabeth Wells, but the couple would have no other children.

When the Sugar Act was implemented in 1764 and the Stamp Act the following year, Adams was a primary opponent, arguing that the acts went against the British Constitution as laid out by Parliament, stating that they would hurt the economy and supporting boycotts to repeal the taxes.

By this time, Adams was 42 years old and had never shown much aptitude for business; he had lost most of the property his father had left him. He soon gave up all kinds of private business, devoting his time and strength to public life. As a result, he and his family had to live on the very small salary he received as clerk of the Assembly of Massachusetts. Despite how poor he was, he couldn’t be bought by the British, always sticking to his Puritan values.

After violence erupted over the Stamp Act and colonists compelled stamp distributors to resign, British merchants convinced Parliament to repeal the tax. But this would not be the end. Parliament would soon take a different approach to raising revenue, passing the Townshend Acts in 1767. These acts imposed new taxes on goods imported into the colonies, including glass, lead, paper, and tea. Resistance to the Townshend Acts grew, and Adams soon organized a boycott in Boston. Before long, other towns in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut had joined the boycott.

The opposition to the new taxes was just as bitter as it had been against the Stamp Act. Samuel Adams urged the people of Boston and Massachusetts to refuse to import any goods from England as long as Parliament imposed the new taxes. This inflicted significant injury upon English merchants, as they had done two or three years before.

The British merchants again begged for a repeal, but King George could not understand the Americans; where he had thus far not been able to coerce them, he made a cunning attempt to outwit them.

Influenced by the King, Parliament removed all the new taxes except the one on tea. “There must be one tax to keep the right to tax,” the King said. He would carry his point if he could only get the Americans to submit to paying any tax — no matter how small — that Parliament might levy. He, therefore, urged not only the removal of all taxes except the one on tea but also made arrangements whereby Americans could buy their taxed tea cheaper than it could be bought in England and cheaper even than they could smuggle it from Holland as they had been doing. No doubt, the King had great faith in his foolish scheme. “Of course,” he argued, “the Americans will buy their tea where they can buy it cheapest, and then we will have them in a trap.” But this would be a colossal blunder.

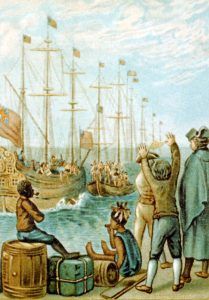

The East India Company arranged to ship cargoes of tea to Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and Charleston. When the tea arrived, the people in New York and Philadelphia refused to let it land, and in Charleston, they stored it in damp cellars, where it spoiled. But there was a most exciting time in Boston when the Tory Governor, Thomas Hutchinson, was determined to fight a hard battle for the King. The result was the famous “Boston Tea Party.”

It was a quiet Sunday morning on November 28, 1773, when the Dartmouth, one of the three tea ships on the way to Boston, sailed into the harbor. The people were attending service in the various churches when the shout, “The Dartmouth is in!” spread like wildfire, and soon the streets were astir with people.

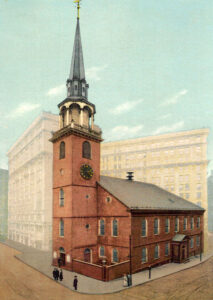

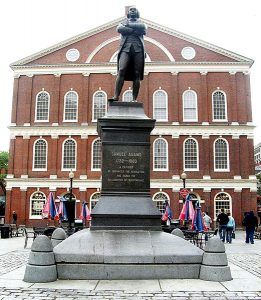

Fearing that the tea might be landed, several people quickly got together and secured a promise from Benjamin Rotch, the owner of the Dartmouth, that the tea should not be landed before Tuesday. On Monday morning, an immense town meeting was held in Faneuil Hall, the “Cradle of Liberty.” Five thousand men were present. But, Faneuil Hall proving too small, the crowd had to reach the Old South Church. In addressing the meeting, Samuel Adams asked, “Is it the firm resolution of this body that the tea shall not only be sent back but that no duty shall be paid thereon?” With a great shout, the men answered, “Yes.” The other two ships arrived a few days later.

Samuel Adams, the people of Boston, and the surrounding towns determined that the tea should not be landed. Governor Hutchinson was equally determined that it should be. The advantage was with the governor, for according to law, the vessels could not return to England with the tea unless they got a clearance from the Collector of Customs or a pass from the governor.

Neither the Collector of Customs nor Governor Hutchinson would yield an inch. For 19 days, the struggle continued, growing more bitter daily. With a stubborn purpose to prevent the tea landing even if they had to fight, the Boston people appointed men armed with muskets and bayonets, some to watch the tea ships by day and some by night. Six couriers were ready to mount their horses, which they kept saddled and bridled and speed into the country to alarm the people. Sentinels were stationed in the church belfries to ring the bells, and beacon fires were ready to be lit on the surrounding hilltops.

The morning of December 16 had come. If the tea remained in the harbor until the next day – the 20th day – the revenue officer would be legally empowered to land it by force. Men, talking angrily and shaking their fists with excitement, thronged into the streets of Boston from surrounding towns. Over 7,000 had assembled in the Old South Church and the streets outside by ten o’clock.

They were waiting for the coming of Benjamin Rotch, who had gone to see if the collector would give him clearance. Rotch told the angry crowd that the collector refused to give the clearance. The people told him that he must get a pass from the governor. Fearing for his safety, the poor man started to find Governor Hutchinson, who had purposely retired to his country home at Milton. Then, the meeting adjourned for the morning.

At three o’clock, a great multitude of eager men again crowded into the Old South Church and the streets outside to wait for the return of Rotch. It was a critical moment. “If the Governor refuses to give the pass, shall the revenue officer be allowed to seize the tea and land it tomorrow morning ?” Many anxious faces showed that men were asking themselves this momentous question.

But while, in deep suspense, the meeting waited and deliberated, a merchant named John Rowe said, “Who knows how tea will mingle with salt water? “A whirlwind of applause swept the assembly and the masses outside the church. As daylight deepened into darkness, candles were lighted. Shortly after 6:00, Benjamin Rotch entered the church and, with a pale face, said, “The Governor refuses to give a pass.” An angry murmur arose, but the crowd soon became silent when Samuel Adams arose and said, “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.”

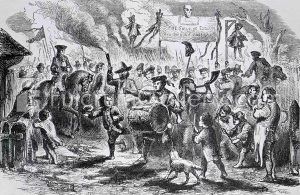

This was a concerted signal. In an instant, a war-whoop sounded, and forty or fifty “Mohawks,” or men dressed as Indians waiting outside, dashed past the door and down Milk Street toward Griffin’s Wharf, where the tea ships were lying at anchor. It was a bright moonlit night, and everything could be seen. Many men stood on the shore and watched the “Mohawks” as they broke open 342 chests and poured the tea into the harbor. There was no confusion. All was done in perfect order.

The “Boston Tea Party,” of which Samuel Adams was the prime mover, was a long step toward the American Revolution. Samuel Adams was, at this time, almost or entirely alone in his desire for Independence, and he has well been called the “Father of the Revolution.” But, his influence for the good of America continued far beyond the time of the “Boston Tea Party.” Up to the last, his patriotism was earnest and sincere.

He remained in politics, serving as Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor and Governor. He retired from politics at the end of his term as governor in 1797. He died at the age of 81 on October 2, 1803, and was interred at the Granary Burying Ground in Boston.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

About this Article: Though several sources were used for some of the content, much of the text, as it appears here, is excerpted from Wilbur F. Gordy’s book, American Leaders and Heroes, published in 1903. However, the article is far from verbatim as much information has been added, and much of the original text is heavily edited.

Also See:

Heroes and Patriots of America