From the book “My Dinner with The Founding Fathers: A Collection of Short Stories About Dining with the Men Who Built America“ by A.L. Talarowski

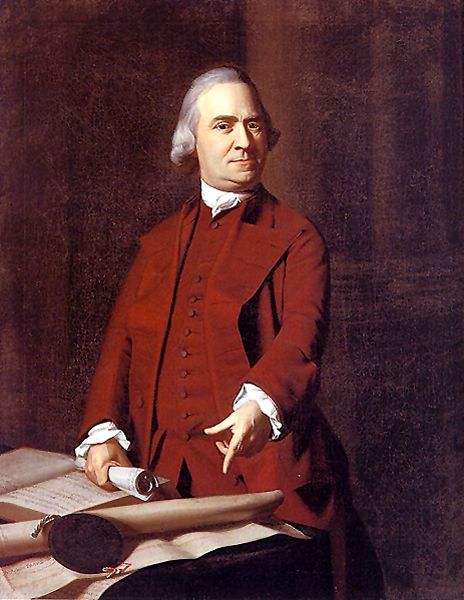

Samuel Adams

I love fall weather. A crisp autumn evening is a perfect time for sitting around a bonfire, enjoying the outdoors – and of course – stuffing yourself silly with delicious, ooey-gooey s’mores! I have had a lot of good times around the campfire before, but one night will forever stand out above the rest.

It started like any other fireside night; with friends and family gathered around, we set ablaze the pile of wood that we had collected. Once satisfied with the height and diameter of the fire, we sat around, sharing stories and singing songs. But then, something weird happened. Now, I am not about to declare that I saw a flying alien spacecraft or Bigfoot running through the woods… but then again, that may be more believable. I walked over to a cooler and pulled out a bottle of ale when Samuel Adams suddenly materialized before my eyes.

It was as if time had stopped – or at least slowed; my family and friends were moving in slow motion, seemingly oblivious to the historical figure in our midst. I thought I must be imagining things.“So, this is how history remembers me? As a figure on a bottle of alcohol?” The legendary figure said, exacerbating my confusion – and my excitement.

“Uh… I think it’s supposed to be complimentary.” I offered, not quite knowing what to say.

He smiled and let out a small chuckle. “Of course it is!” He said gleefully.

“Sir, what are you doing here, if you don’t mind me asking? How did you get here?”

“I was hoping you could tell me. I have been popping up at bonfires for the past forty years! I guess it has something to do with this,” he said, picking up a bottle and pointing to the label.

I didn’t know if I should take him seriously or not. I didn’t know if he was there or not. Could I be hallucinating? Did I hit my head? I couldn’t possibly be inebriated; I hadn’t even taken my first sip!

“Tell me, what’s going on in the world today?”

That felt like a loaded question. I was about to take a sip of my drink, then thought better of it. I decided that if this was real, I wanted there to be no chance of forgetting it. “Well, sir, America has grown into a nation of fifty great states… well, okay – forty-nine great states, and New Jersey.” I waited for a reaction, but he just stood there, staring at me. I awkwardly snickered at my own decidedly 21st-century joke and moved on. I gave him a quick, forty-five-minute, two-century rundown on America. Then, I decided that I would need that drink after all.

“Merciful God! Inspire thy people with wisdom and fortitude and direct them to gracious ends. In this extreme distress… save our country from impending ruin – Let not the iron hand of tyranny ravish our laws and seize the badge of freedom…”[1]

I blinked at him. I could not be making this up. My imagination can be pretty vivid, but this guy was animated. Far too animated to be something I just conjured up in my mind’s eye.

“Uh, yeah.” I managed to get out while I was still processing what was happening.

“Fear not! The people will arise.” He proclaimed passionately. “The love of liberty is interwoven in the soul of a man and can never be totally extinguished”[2]

Still confounded and a little taken aback by his unbridled enthusiasm, I muttered, “Right. Um… Yeah. Yes. Yes, I agree.” My brain worked quickly to catch up.

He raised his brows, unconvinced by my response. He grew determined to ignite a fire in me. He clenched his fist and projected loudly, “Is it not high time for the people of this country explicitly to declare whether they will be freemen or slaves? It is an important question which ought to be decided. It concerns us more than anything in this life. The salvation of our souls is interested in the event: for wherever tyranny is established, immorality of every kind comes in like a torrent…”[3]

With that, I came quickly to realize that what was happening was, in fact, happening. Samuel Adams was here, somehow, and I had been given the opportunity to hear his thoughts. I finished his passionate lecture, remembering the article from my studies. “…It is in the interest of tyrants to reduce the people to ignorance and vice. For they cannot live in any country where virtue and knowledge prevail. The religion and public liberty of a people are intimately connected; their interests are interwoven; they cannot subsist separately; and therefore, they rise and fall together. For this reason, it is always observable that those who are combined to destroy the people’s liberties practice every art to poison their morals. How greatly then does it concern us, at all events, to put a stop to the progress of tyranny.”[4]

He smiled, clearly proud that his inspirational writings have stood the test of time – still being studied some 250 years later.

I smiled back but then quickly dropped the corners of my mouth when I thought about the reality of those words being played out before my very eyes. “I believe that the poisoning of morals has indeed become a fine art to many in Congress. They search to identify harmful secular trends in society and exploit any issue – using the vanity of the people – to gain for themselves more control. It is clear to me that some in power – or those desperately trying to obtain power – are trying to promote harmful narratives to encourage a society where morals are ‘fluid,’ as they say, and vices are celebrated, allowing them to perpetuate this circle of power and poison.”

First Continental Congress, September 1774, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

“Few men are contented with less power than they have right to exercise, the ambition of the human heart grasps at more.[5] I need not remind you that men of this character have had seats in Congress from the beginning…[6] Let each citizen remember at the moment he is offering his vote that he is not making a present or compliment to please an individual – or at least that he ought not so to do; but that he is executing one of the most solemn trusts in human society for which he is accountable to God and his country.[7] The liberties of our country, the freedom of our civil Constitution, are worth defending at all hazards, and it is our duty to defend them against all attacks. We have received them as a fair inheritance from our worthy ancestors: they purchased them for us with toil and danger and expense of treasure and blood and transmitted them to us with care and diligence. It will bring an everlasting mark of infamy on the present generation, enlightened as it is, if we should suffer them to be wrestled from us by violence without struggle or to be cheated out of them by the artifices of false and designing men.[8]”

“What should we be doing to preserve our freedoms now and for future generations?” I asked.

“As piety, religion and morality have a happy influence on the minds of men, in their public as well as private transactions, you will not think it unseasonable… to bring to your remembrance the great importance of encouraging our university, town schools, and other seminaries of education, that our children and youth while they are engaged in the pursuit of useful science, may have their minds impressed with a strong sense of the duties they owe to their God, their instructors and each other, so that when they arrive to a state of manhood, and take a part in any public transactions, their hearts having been deeply impressed in the course of their education with the moral feelings – such feelings may continue and have their due weight through the whole of their future lives.[9] A general dissolution of principles and manners will more surely overthrow the liberties of America than the whole force of the common enemy. While the people are virtuous, they cannot be subdued; but when once they lost their virtue, they will be ready to surrender their liberties to the first external or internal invader. How necessary, then, is it for those who are determined to transmit the blessings of liberty as a fair inheritance to posterity, to associate on a public principle in support of public virtue?[10]” Adams answered squarely.

I agreed, then took the conversation in a slightly different direction. “You have always been very clear about your feelings that states should hold great authority versus the federal government being the supreme centralized power over the entirety of the land and the people. Fortunately, because America was not built with a sole and strong centralized power, states have oft acted to protect certain rights and freedoms and augmented their own economic growth by keeping taxes low and regulations to a minimum. We have also seen states stand up to the federal government for the protection of their citizens. Structuring the government so that its strength is greatest at the individual level and then decreases with each step from local to state to federal is – I believe – what’s allowed such a large and diverse country to last as long as it has while remaining free.”

“I am fully persuaded that the population of the U.S. living in different climates, of different education and manners, and possessed of different habits and feelings under one consolidated government cannot long remain free, or indeed remain under any kind of government but despotism.[11] And can this national legislature be competent to make laws for the free internal government of one people living in climates so remote whose habits and particular interests are and probably always will be so different? Is it to be expected the general laws can be adapted to the feelings of the more eastern and the more southern parts of so extensive a nation? …But should we continue distinct sovereign states, confederated for the purposes of mutual safety and happiness, each contributing to the federal head such a part of its sovereignty as would render the government fully adequate to those purposes and no more, the people would govern themselves more easily, the laws of each state being well adapted to its own genius and circumstances, and the liberties of the United States would be more secure…[12] I mean… to let you know how deeply impressed with a sense of the importance… that the good people may clearly see the distinction – for there is a distinction – between the federal powers vested in Congress and the sovereign authority belonging to the several states, which is… the private and personal rights of the citizens.[13]” Adams agreed. Then, he eyed the bag of marshmallows and quickly changed the subject. “Say, can I have s’more?!”

“I am fully persuaded that the population of the U.S. living in different climates, of different education and manners, and possessed of different habits and feelings under one consolidated government cannot long remain free, or indeed remain under any kind of government but despotism.[11] And can this national legislature be competent to make laws for the free internal government of one people living in climates so remote whose habits and particular interests are and probably always will be so different? Is it to be expected the general laws can be adapted to the feelings of the more eastern and the more southern parts of so extensive a nation? …But should we continue distinct sovereign states, confederated for the purposes of mutual safety and happiness, each contributing to the federal head such a part of its sovereignty as would render the government fully adequate to those purposes and no more, the people would govern themselves more easily, the laws of each state being well adapted to its own genius and circumstances, and the liberties of the United States would be more secure…[12] I mean… to let you know how deeply impressed with a sense of the importance… that the good people may clearly see the distinction – for there is a distinction – between the federal powers vested in Congress and the sovereign authority belonging to the several states, which is… the private and personal rights of the citizens.[13]” Adams agreed. Then, he eyed the bag of marshmallows and quickly changed the subject. “Say, can I have s’more?!”

“Of course,” I responded with a smile. I grabbed a couple of roasting sticks and pushed on some marshmallows. “So, you think we will be okay?” I asked with renewed hope.

We put our marshmallows over some hot embers on the perimeter of the large fire, and he answered. “I cannot help thinking that this union among the Colonies… can be attributed to nothing less than the Agency of the Supreme Being. If we believe that he superintends and directs the great affairs of empires, we have reason to expect the restoration and establishment of the public liberties, unless by our own misconduct we have rendered ourselves unworthy of it; for he certainly wills the happiness of those of his creatures who deserve it, and without public liberty, we cannot be happy.”[14]

I assembled the s’mores, and while we ate them, he asked me a few more questions about the span of time that had gone by since his days in Congress.

I was about to ask him more about the founding when he wiped the chocolate from the corners of his mouth with his handkerchief and stood up. “Well dear, it was so sweet conversing with you, but I really must be going.”

“No!” I pleaded too eagerly. I quickly worked to regain my composure. “I mean, I have so much more I wanted to talk about.”

His body started to flicker and fade, then he became practically see-through. “I’m afraid I don’t have much time.” He said, looking down at his torso. “Everything will be okay.” He gave compassionately.

“Do you have any last words of wisdom for me?”

“If you carefully fulfill the various duties of life, from a principle of obedience to your heavenly Father, you shall enjoy that peace which the world cannot give nor take away… you know you cannot gratify me so much, as by seeking most earnestly the favor of Him who made and supports you – who will supply you with whatever His infinite wisdom sees best for you in this world, and above all, who has given us His Son to purchase for us the reward of eternal life.”[15]

And then he vanished. He was gone as quickly as he came. I was saddened by his departure, yet full of hope for the future. Something about his words really encouraged and emboldened me.

©A.L. Talarowski, for Legends of America, updated February 2024.

If you enjoyed this reading, you could get 12 more unique stories in My Dinner With The Founding Fathers: A Collection of Short Stories About Dining with the Men Who Built America, available at Amazon and Under The Sun Publishing. It is also available as a theatrical reading on Audible. This book was voted an award-winning finalist in American Book Fest’s American Fiction Awards.

About the Author: A.L. Talarowski is the award-winning author of My Dinner With The Founding Fathers: A Collection of Short Stories About Dining with the Men Who Built America. She has a deep love of country and a passion for sharing true American history with others.

Also See:

Samuel Adams and the Boston Tea Party

Boston, Massachusetts – The Revolution Begins

Sources:

[1] Samuel Adams, “Article Signed ‘Valerius Poplicola’,” October 5, 1772. The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. II, 1770-1773, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1906, pp. 332-337. [Original source: Boston Gazette, October 5, 1772.]

[2] Samuel Adams, “Letter to John Adams,” October 4, 1790. The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. IV, 1778-1802, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1908, pp. 340-344.

[3] Samuel Adams, October 5, 1772. The Writings of Samuel Adams vol. II, ed. Cushing, pp. 332-337.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Samuel Adams, “Letter to Richard Henry Lee,” April 22, 1789. The Writing of Samuel Adams, vol. IV, ed. Cushing, pp. 326-327.

[6] Samuel Adams, “Letter to Richard Henry Lee,” January 15, 1781. Ibid, pp. 239-241.

[7] Samuel Adams, “Article, Unsigned,” April 16, 1781. Ibid, pp. 255-258. [Original source: Boston Gazette, April 16, 1781.]

[8] Samuel Adams, “Article Signed ‘Candidus’,” October 14, 1771. The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. II, ed. Cushing, pp. 250-256. [Original source: Boston Gazette, October 14, 1771.]

[9] Samuel Adams, “Letter to the Legislature of Massachusetts, January 16, 1795,” January 16, 1795. The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. IV, ed. Cushing, pp. 369-374.

[10] Samuel Adams, “Letter to James Warren,” February 12, 1779. Ibid, pp. 123-125.

[11] Samuel Adams, “Letter to Elbridge Gerry,” August 22nd, 1789. Ibid, pp. 330-332.

[12] Samuel Adams, “Letter to Richard Henry Lee,” December 3rd, 1787. Ibid, pp. 323-326.

[13] Samuel Adams, “Letter to Richard Henry Lee,” August 24, 1789. Ibid, pp. 333-335.

[14] Samuel Adams, “Letter to an Unknown Correspondent,” March 12, 1775. From The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. III, 1773-1777, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907, pp. 198-200.

[15] Samuel Adams, “Letter to Hannah Adams,” August 17, 1780. The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. IV, ed. Cushing, pp. 200-201.