Established in 1857 along the Oregon and California Trails, Rock Creek Station, near what is now Fairbury, Nebraska, is today preserved as a Nebraska State Park.

The history here is rich in its tales of emigrating pioneers and legends of the Old West. Located along the west bank of Rock Creek, the station served as a supply center and resting spot for the many travelers headed westward in the 19th century.

When it was originally built by S.C. Glenn, the “station” consisted of little more than a cabin, a barn, and a makeshift store, where Glenn sold limited supplies, hay, and grain.

In the Spring of 1859, David C. McCanles and his brother, James, were on their way to the Colorado goldfields.

David became discouraged as he met miners returning from Colorado with nothing in their pockets but disappointment. Changing tactics, David McCanles bought the Rock Creek Station from Glenn in March, deciding to take up “road ranching” rather than gold prospecting.

McCanles continued to operate the small store and built a toll bridge across the creek. Before the bridge, pioneers were required to hoist and lower their wagons into the creek before pulling them up on the other side – quite a tedious process that could take hours for each wagon. When the toll bridge opened, each wagon paid from 10¢ to 50¢ to cross the bridge, depending on their load size and ability to pay. McCanles also built a cabin and dug a well on the east side of Rock Creek, which became known as the East Ranch.

The following year, McCanles leased the East Ranch to the Russell, Waddell, and Majors Company, which owned the Overland Stage Company and founded the Pony Express. They installed Horace G. Wellman as their company agent and station keeper and hired James W. “Doc” Brink as a stock tender. Later, the company arranged with McCanles to buy the station with a cash down payment and the remainder in installments.

The East Ranch was then used as a stage and Pony Express relay station, while the West Ranch continued to be used as an emigrant rest stop, a freight station, and the home of the McCanles family.

In April 1861, McCanles sold the West Ranch to freighters Hagenstein and Wolfe and moved his family to another location about three miles south of Rock Creek Station. Always trying to make money, McCanles sold the toll bridge several times, each time with specific requirements in the contract. When the new owner failed to meet the stipulations, he would take it back and resell it.

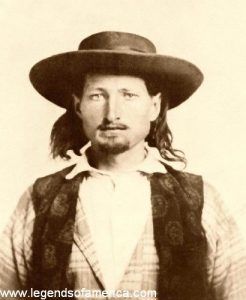

In April or early May of 1861, the station hired then-24-year-old stock tender James Butler “Bill” Hickok, and he became immediately at odds with David McCanles, who had earned a reputation as the local bully. Allegedly, McCanles teased Hickok unmercifully about his girlish build and feminine features, as well as nicknaming him “Duck Bill,” referring to his long nose and protruding lips.

Perhaps in retaliation, Hickok began courting a woman named Kate Shell, who, even though McCanles was married, apparently had his eye on.

In the meantime, the Overland Stage Company had fallen behind on its installment payments, and on July 12, 1861, McCanles, along with his 12-year-old son, Monroe, and two friends by the names of James Woods and James Gordon, came to the station to inquire about the status of the installments.

An argument ensued not long after their arrival, and profanities were exchanged, soon leading to gunfire. In the melee, Hickok shot David McCanles, and both James Woods and James Gordon, who was seriously wounded, later died of their wounds. Twelve-year-old Monroe escaped to his home, some three miles south of Rock Creek.

Though the details of what happened on that fateful day continue to be debated, the versions vary widely. Monroe McCanles, who witnessed the entire event, told a version of the following: When David McCanles had not received full payment from the Overland Stage Company, he planned to take it up with the station manager, Horace Wellman. That very day, the station manager allegedly went to the company office in Brownville to obtain the money, but he returned empty-handed.

Upon hearing this, an angry McCanles soon arrived with two options: either collect the money owed or repossess the ranch. Showing up with his son and two employees – James Woods and James Gordon- McCanles called for Wellman to come out. Instead, the station manager’s wife, Jane Wellman, appeared at the door, closely followed by James (Bill) Hickok. Horace Wellman’s specific whereabouts are unknown, but he was close by.

Disconcerted by Hickok’s interference, McCanles allegedly asked, “Jim, haven’t we been friends all the time?” After Hickok assured him they were, McCanles, biding his time, asked for a drink of water and came inside. The other three stayed outside the cabin.

Suddenly, McCanles sensed danger, returned the dipper, and moved toward the other door when Hickok moved behind a curtain partition. Unarmed, McCanles said, “Now, Jim, if you have anything against me, come out and fight me fair.”

However, Hickok’s answer was a blast from a rifle, killing McCanles and dropping him to the floor. Ironically, the story tells that it was McCanles’ own rifle that he had left with Wellman to defend the station where he was killed. Woods and Gordon rushed toward the cabin, hearing the blast, but Hickok’s Colt revolver stopped Woods. In the meantime, Wellman bludgeoned him with a hoe until he died. Gordon, who was also wounded by gunfire, fled to the creek but was followed by Doc Brink, the station’s stock tender, who killed him with a blast from his shotgun. Monroe dodged a blow from Wellman’s hoe and escaped to his home some three miles south.

McCanles and Woods were originally buried in a crude box on Soldier Hill. Gordon was buried in a blanket at the spot where he was killed near Rock Creek. In the early 1880s, the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad construction intersected Soldier Hill, and the bodies of McCanles and Woods were re-interred at the Fairbury Cemetery.

In the meantime, James A. McCanles, David’s brother, filed an arrest warrant for Hickok, Wellman, and Brink on July 15, 1861, and the trio was charged for the murders of McCanles, Woods, and Gordon. A trial was held in Beatrice, and though Monroe McCanles adamantly claimed that his father and the other two men were unarmed, he was not allowed to testify because of his age. After the trio pleaded self-defense and defense of company property, all three were acquitted.

Later, when Hickok’s fame began to spread, he told a different version of the tale, making McCanles out to be a ruthless killer and an outlaw who led a vicious gang terrorizing the region. This story, told by Colonel Ward Nichols and published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1867, tells a version embellished to the degree that Wild Bill had polished off ten of the West’s most dangerous desperados and was left with eleven buckshot and 13 knife wounds.

Hickok’s tale describes himself as scouting for the U.S. Cavalry detachment when he arrived at Rock Creek that fateful day, rather than working as a stock tender. Describing the McCanles’ Gang as reckless, blood-thirsty devils, he said he came upon the station to hear a tale from Mrs. Wellman that McCanles was within minutes of the cabin, dragging a preacher by his neck with a rope.

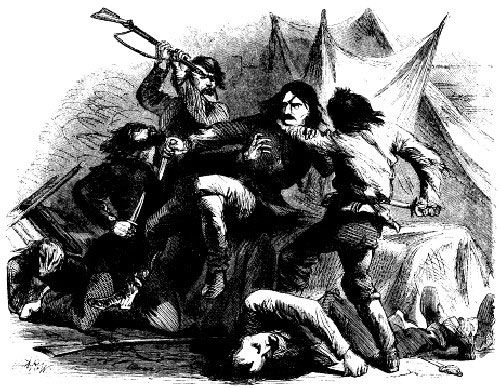

Wild Bill Hickok takes on the McCanles gang single-handedly.

His tale describes how he fought off the entire McCanles Gang with only a revolver and a bowie knife, killing all of them in the end and spending weeks recovering from his own injuries. (The entire tale can be read in this article: Wild Bill)

This event, called the McCanles Massacre by writers, began the Wild Bill Hickok legend. Though Hickok’s “legend” was already well-known when the article appeared in Harper’s Magazine in 1867, Nichol’s glamorized version of the fighting frontier hero further perpetuated his fame.

No one knows the specifics of this bloody and seemingly one-sided fight. Numerous versions have been provided, including tales of jealousy, theft, and the ongoing conflict between the North and South. Some tales even allege that it was not Bill Hickok who killed McCanles but Horace Wellman.

Continuing to be scrutinized years after the incident and long after Bill Hickok’s death, a man named F.G. Elliott was interviewed by a Works Progress Administration writer in 1938. Though not supporting the glorified story told by Nichols in Harper’s Magazine, his tale does support Hickok’s rightful killing of David McCanles. Depending upon your point of view, it may or may not shed more light on the actual events of that fateful day. To see the interview, click HERE.

By 1866, the railroad had reached Kearney, Nebraska, and trail traffic dramatically diminished, leaving the road ranchers to find other occupations.

In 1980, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission began to develop the area as a state historical park. Today, the buildings of the original Rock Creek Station and Pony Express have been reconstructed in the park, which now includes some 350 acres, a visitor’s center, hiking trails, picnic areas, and a campground. The terrain includes prairie hilltops, timber-studded creek bottoms, and rugged ravines, along with the deep ruts of the Oregon and California Trails, carved more than a century ago by the many wagons that traveled westward along this path.

Contact Information:

Rock Creek State Park

57426 710th Rd

Fairbury, Nebraska 68352-5550

402-729-5777

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

Also See:

McCanles Massacre – A WPA Interview

Wild Bill – 1867 Harper’s Weekly Article

Wild Bill Hickok & the Deadman’s Hand

See Sources.