One of America’s great rags to riches stories and a pioneer not only for women but also African Americans, Madame C.J. Walker blazed a path as the first black woman millionaire and is argued as the first self-made woman millionaire in the U.S.* Her struggles and accomplishments continue as a shining example of American entrepreneurship.

She was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867. The youngest of six children, Sarah was the first in the family officially born “free,” just a couple of years after the Emancipation of slaves in the U.S. Her parents, Owen and Minerva Breedlove, along with her older siblings, were slaves on a Delta, Louisiana cotton plantation; the same plantation where she was born.

Sarah experienced hardship early; her mother died when she was only five, and her father only a couple of years later. Orphaned at the age of 7, she went to live with her older sister and brother-in-law in Vicksburg, Mississippi. There she would continue working cotton fields until trouble with her brother-in-law is believed to have led her to marry at age 14 to escape abuse.

She and her husband, Moses McWilliams, would have a daughter, Lelia (a.k.a. A’Lelia), in June of 1885, but the young couple’s future was short, as Moses died just two years later, leaving Sarah a widow at the age of twenty.

With her two-year-old daughter in tow, Sarah decided to leave the South and head for St. Louis, Missouri, where some of her brothers had become barbers after leaving Louisiana as “Exodusters” years before. Finding work as a laundress and cook, Sarah toiled for $1.50 a day. In 1894 she married her second husband, John Davis, but his unreliability as a spouse led her to leave him around 1903.

During this time, like many black women, Sarah suffered hair loss due to poor diet and infrequent hair washing, leading to scalp disease. Sarah learned about hair care from her brothers. During the World’s Fair of 1904, she discovered Annie Turnbo, another African American hair care entrepreneur, and became a commission agent for Turnbo’s Poro Company. Applying the knowledge from her brothers and Poro, Sarah began experimenting with solutions for her own hair-loss issue. Around the same time, Sarah began dating Charles Joseph Walker, a St. Louis Clarion newspaper salesman.

In 1905, Sarah and her daughter moved to Denver, Colorado, where her sister-in-law’s family lived. Charles soon followed, and the two were married in 1906, with Sarah officially changing her name to Madame C.J. Walker.

Continuing to sell products for Turnbo’s Poro company, Walker awoke from a dream, from which she is quoted as saying, “A big black man appeared to me and told me what to mix up for my hair. Some of the remedy was grown in Africa, but I sent for it, put it on my scalp, and in a few weeks, my hair was coming in faster than it had ever fallen out.” With a starting investment of $1.25, her new hair concoction would be called “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.”

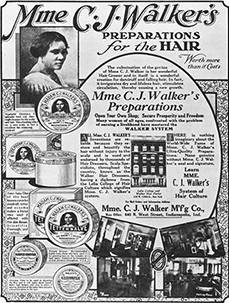

Walker proved to be a marketing guru, selling her hair product door to door, at churches and clubs, and even a mail-order catalog, promoting not only a hair care system but also teaching other black women how to groom and style their hair and, of course, sell her product. Using her own image on the packaging with before and after pictures helped her overall image. Her now 21-year-old daughter A’Lelia was in charge of the mail-order operation in Denver while she and her husband Charles traveled the south and eastern U.S. to expand the business.

Madam C J Walker Manufacturing Company, Indianapolis, Indiana

By 1908, Walker and her husband moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, establishing the Lelia College for “hair culturists,” then moved on to Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1910, where she established the headquarters for Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company. In the meantime, the Denver operation was shut down in 1907, with A’Lelia taking over the Pittsburgh operation. During this time, Walker encouraged other black women to become successful in business, teaching them the “Walker Beauty Method” and employing many of them as key executives in her company.

When her marriage to Charles Walker fell apart in 1912, Madame C.J. had made such a name for herself that she insisted on keeping his name. She trained almost 20,000 women as “Walker Agents,” It was hard to miss her heavy advertising that was prominent in magazines and African American newspapers of the day. Walker is quoted as saying in 1914, “I am not merely satisfied with making money for myself; I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race.”

Walker was an advocate for education and donated thousands to African American charities. In 1916, she moved to New York City, leaving her company’s day-to-day operations to her management team in Indianapolis. Her daughter A’Lelia had moved to New York in 1913. Here, Walker became more political, delivering lectures on social and economic issues at black institution conventions. In 1917, she joined the NAACP, and in 1918 the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs honored Walker for making the largest individual contribution to help preserve Frederick Douglass’ Anacostia house. Also, in 1917, the Madame C.J. Walker Hair Culturists Union of America Convention in Philadelphia is said to have been one of America’s first national meetings of businesswomen.

Upon her death on May 25, 1919, from kidney failure and complications of hypertension, she left almost $100,000 to orphanages, institutions, and individuals, as well as directing two-thirds of future profits of her estate to charity. At the time of her death, she was considered the wealthiest African American woman in the U.S. In 1927, the Walker Building, an arts center in Indianapolis that she worked toward before her death, opened in Indianapolis and is now a National Historic Landmark. Among many honors since Madame C.J. Walker was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993, and in 1998 the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp in her honor.

*Though she was eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America, Walker’s estate was worth an estimated $600,000 when she died.

Madam C J Ad

©Dave Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2022.

Also See:

Women’s Suffrage in the United States

Sources:

Madam C.J. Walker

Bio.

Indiana Historical Society

PBS

Wikipedia