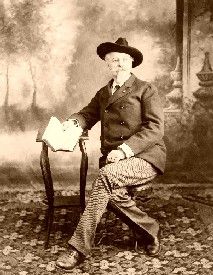

By Henry Inman and William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, 1898

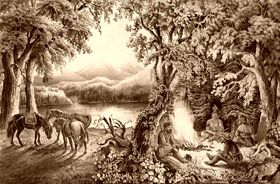

The majority of old-time trappers and scouts always had an inexhaustible fund of anecdote and adventure. Stories were often told at night when the day’s duty of making the round of the traps was done, the beaver skinned, and the pelts hung up to cure. Their simple supper disposed, and being comfortably seated around their fire of blazing logs, each indulged, as a preliminary, in his favorite manner of smoking. Some adhered to the traditional clay pipe; others, more fastidious, used nothing less expensive than meerschaum. Many, however, were satisfied with a simple cigarette with its covering of corn husk. This was Kit Carson’s usual method of smoking, and he was an inveterate partaker of the weed. Frequently, there was no real tobacco in the camp; either its occupants had exhausted their supply, or the traders had failed to bring enough at the last rendezvous to go round.

Then, they were compelled to resort to the substitutes of the Indians. Among some tribes, the bark of the red willow, dried and bruised, was used; others, particularly the mountain savages, smoked the genuine kin-nik-i-nick, a little evergreen vine growing on the tops of the highest elevations and known as larb.

It was a rare treat to come across one of those solitary camps when out on a prolonged hunt, for the visitor was sure of a cordial welcome, and everything the generous men had was freely at your service. The crowning pleasure came at night when stories were told under the silvery pines, with troops of stars overhead, around a glowing campfire, until the lateness of the hour warned all that it was time to roll up in their robes if they intended to court sleep.

Let the reader, in fancy, accompany us to some thunder-splintered canyon of the great rock-ribbed Continental Divide, and when the shadows of the night come walking along the mountains, seek one of these sequestered camps, take our place in the magic circle and listen to wondrous tales as they are passed around. Nothing is to disturb the magnificent silence save an occasional soughing of the fitful breeze in the tops of the towering pines or the gentle babbling of some tiny rivulet as its water soothingly flows over the rounded pebbles in its bed. There is a charm in the environment of such a spot that will photograph its picture on the memory as the gem of all the varied experiences of a checkered life.

One of the best raconteurs was Old Hatcher, as he was known throughout the mountains. He was a famous trapper of the late ’40s. Hatcher was thoroughly Western in all his gestures, moods, and dialect. He had a fund of stories of an amusing and often marvelous cast. It was never trouble to persuade him to relate some of the scenes in his wayward, ever-changing life, particularly if you warmed him up with a good-sized bottle of whiskey, which he was inordinately fond of.

When telling a story, he invariably kept his pipe in his mouth, using his hands to cut from a solid plug of Missouri tobacco whenever his pipe showed signs of exhaustion. He also fixed his eyes on some imaginary object in the blaze of the fire, and his countenance indicated a concentration of thought as if to call back from the shadowy past the coming tale, the more attractive, perhaps, by its extreme improbability.

He declared that he once visited the realms of Pluto, and no one ever succeeded in disabusing his mind of the illusion.

The story is here presented just as he used to tell it but divested of much of its dialect, so hard to read and much more difficult to write:

“Well!” beginning with a vigorous pull at his pipe. “I had been down to Bent’s Fort to get some powder, lead, and a few things I needed at the beginning of the buffalo season. I remained there for some time, waiting for a caravan to come from the States, which was to bring the goods I wanted. Things were wonderfully high; it took a beaver skin for a plug of tobacco, three for a cup of powder, and other knick-knacks in proportion. Jim Finch, an old trapper who went under by the Ute near the Sangre de Cristo Pass a few years ago, had told me there was lots of beaver on the Purgatoire. Nobody knew it; all thought the creeks had been cleaned out of the creatures.

So down I go to the canyon and set my traps. I was all alone by myself, and I’ll be darned if ten Injuns didn’t come screeching right after me. I cached. I did, and the darned red devils made for the open prairie with my animals. I tell you, I was mad, but I kept hidden for more than an hour. Suddenly, I heard a tramping in the bushes, breaking my little gray mule. Thinks I them ‘Rapahoes ain’t smart; so tied her to grass. But the Injuns had scared the beaver, so I stayed in my camp, eating my lariat. Then I began to get kind o’ wolfish and squeamish; something was gnawing and pulling at me inwards, like a wolf in a trap. Just then, I thought I had been there before trading liquor with the Ute.

“I looked around for sign, and hurrah for the mountains if I didn’t find the cache! And now, if I didn’t kiss the rock I had pecked with my butcher knife to mark the place, I’d be ungrateful. Maybe the gravel wasn’t scratched up from that place, and to me, as would have given all my traps for some Taos lightning, just rolled in the delicious fluid.

“I was weaker than a goat in the spring, but when the Taos was opened, I fell back and let it run in. In four swallows, I decided to pull up stakes for the headwaters of the Purgatoire for meat. So I roped old Blue, tied on my traps, and left.

“It used to be the best place in the mountains for meat, but nothing was in sight. Things looked strange, and I wanted to make the backtrack, but, says I, here I am, and I don’t turn, surely.

“The bushes were all scorched and curly, and the cedar was like a fire had been put to it. The big, brown rocks were covered with black smoke, and the little drink at the bottom of the canyon was dried up. I was now mostly under the old twin peaks of ‘Wa-te-yah’; the cold snow on top looked cool and refreshing.

“Something was wrong; I must be shoving backward, I thought, and that before long, or I’d go under, so I jerked the rein, but I’ll be dog-gone, and it’s true as there’s meat running; Blue kept going forward. I laid back and cussed and kicked till I saw blood, certain. Then I put out my hand for my knife to kill the beast, but the ‘Green River’ wouldn’t come. I tell you some invisible spirit had a paw there, and it’s me that says it, ‘bad medicine’ it was, that trapping time.

“Losing my pistol, the one I traded at Big Horn, the time I lost my Ute wife, and priming my rifle, I swore to keep right on, for after staying ten years in these mountains, to be fooled this way wasn’t the game for me no how.

“Well, we, I say, ‘we,’ for Blue was some — as good as a man any day; I could talk to her, and she’d turn her head as if she understood me. Mules are knowing critters — next to humans. At a sharp corner, Blue snorted and turned her head but couldn’t go back. There, in front, was a level canyon with black and brown and gray stone walls, and stumps of burned piñon hung down, ready to fall onto us; as we passed, the rocks and trees shook and grated and croaked. All at once, Blue tucked her tail, backed her ears, bowed her neck, and squealed right out, a-rearing on her hind legs, a-pawing, and snickering. This hoss didn’t see the cute of them notions; he was for examining, so I went to jump off and lam the fool, but I was stuck tight as if there was tar on the saddle. I took my gun, that iron, and my rifle and popped Blue over the head, but she squealed and dodged, all the time pawing. Still, it wasn’t any use, and I say, ‘You didn’t cost more than two blankets when you were traded from the Ute, and two blankets ain’t worth more than two beaver skins at Bent’s Fort, which comes to two dollars a pair, you consarned ugly picture — darn you, anyhow!’ Just then, I heard a laugh. I looked up, and two black critters — they weren’t human, sure, for they had black tails and red coats — Indian cloth, cloth-like that traded to the Indians, edged with white, shiny stuff, and brass buttons.

“They came forward and made two low bows. I felt for my scalp knife, for I thought they were approaching to take me, but I couldn’t use it — they were so darned polite.

“One of the devils said, with a grin and bow, ‘Good morning, Mr. Hatcher!’

“‘H — — !’ says I, ‘how do you know me? I swear this hoss never saw you before.’

“‘Oh, we’ve expected you a long time,’ said the other, ‘and we are quite happy to see you — we’ve known you since your arrival in the mountains.’

“I was getting sort of scared. I wanted a drop of Taos mighty bad, but the bottle was gone, and I looked at them in astonishment and said — ‘The devil!’

“‘Hush!’ screamed one, ‘you must not say that here — keep still, you will see him presently.’

“I felt streaked, and a cold sweat broke out all over me. I tried to say my prayers, as I used to at home when they made me turn in at night –” ‘Now I lay me.’

“Pshaw! I’m off again. I can’t say it, but if this child could have got off his animal, he’d taken hair and gone down the trail for Purgatoire.

“All this time, the long-tailed devils led my animal, and my top of her, the biggest fool dug out, up the same canyon. The rocks on the sides were pecked smooth as a beaver skin, ribbed with the grain, and the ground was covered with bits of cedar like a graveyard of mules had been nipping and scattering them about. Overhead, it was roofed; leastwise, it was dark in here, and only a little light came through the holes in the rock. I thought I knew where we were and wanted to talk, but I still didn’t ask any questions.

“Presently, we were stopped by a dead wall. No opening anywhere. When the devils turned from me, I jerked my head around quickly, but there was no place to get out — the wall had grown up behind us, too. I was mad, and I wasn’t mad either, for I expected the time had come for this child to go under. So I let my head fall on my breast, and I pulled the wool hat over my eyes and thought for the last of the beaver I had trapped, and the buffalo as had taken my lead pills in their livers, and the poker and euchre I’d played at the Rendezvous at Bent’s Fort. I felt comfortable eating a fat cow to think I hadn’t cheated anyone.

“All at once, the canyon got bright as day. I looked up, and there was a room with lights and people talking, laughing, and fiddles screeching. When I was a boy, Dad and the preacher at home told me the fiddle was the devil’s invention; I believe it now.

“The little fellow holding my animal squeaked out — ‘Get off your mule, Mr. Hatcher!’

“‘Get off!’ said I, for I was mad as a bull pricked with Comanche lances for disturbing me. ‘Get off? I have been trying to ever since I came into this infernal hole.’

“‘You can do so now. Be quick, for the company is waiting,’ says he, pert-like.

“They all stopped talking and were looking right at me. I felt riled. ‘Darn, your company. I’ve got to lose my scalp anyhow, and no difference to me — but to oblige you — so I slid off as easy as if I had never been stuck.

“A hunchback boy, with little gray eyes in his head, took old Blue away. I might never see her again, and I shouted — ‘Poor Blue! Good-by, Blue!’

“The young devil snickered; I turned around mighty stern — ‘Stop your laughing, you hell-cat — if I am alone, I can take you,’ and I grabbed for my knife to wade into his liver, but it was gone — gun, bullet-pouch, and pistol, like mules in a stampede.

“I stepped forward with a big fellow, with hair frizzled out like an old buffalo just before shedding time, and the people jawing worse than a graveyard of paroquets, stopped, while frizzly shouted: –” ‘Mr. Hatcher, formerly of Wapakonnetta, latterly of the Rocky Mountains.’

“Well, there I stood. Things were mighty strange, and every darned n***er looked so pleased. To show them manners, I said, ‘How are you?’ I went to bow but chaw my last tobacco if I could; my breeches were so tight — the heat back in the canyon had shrunk them. They were too polite to notice it, and I felt for my knife to rip the dog-gone things, but recollecting the scalp-taker was stolen, I straightened up and bowed my head. A kind-looking, smallish old gentleman with a black coat and breeches, a bright, cute face, and gold spectacles walks up and presses my hand softly.

“‘How do you do, my dear friend? I have long expected you. You cannot imagine the pleasure it gives me to meet you at home. With much interest, I have watched your peregrinations in the busy, tiresome world. Sit down, sit down; take a chair,’ and he handed me one.

“I squared myself on it, but if a ten-pronged buck wasn’t done sucking when I last sot on a chair, and I squirmed awhile, uneasy as a gun-shot coyote, then I jump up and tells the old gentleman them sort of fixings didn’t suit this beaver, he prefers the floor. I sit cross-legged like in camp, as easy as eating meat. I reached for my pipe — a fellow so used to it — but the devils in the canyon had cached that, too.

“‘You wish to smoke, Mr. Hatcher? — we will have cigars. Here!’ he called to an imp near him, ‘some cigars.’

“They were brought in on a waiter, about the size of my bullet-pouch. I emptied them into my hat, for good cigars ain’t to be picked up on the prairie every day, but looking at the old man, I saw something was wrong. To be polite, I ought to have taken but one.

“‘I beg pardon,’ says I, scratching my scalp, ‘this hoss didn’t think — he’s been so long in the mountains he’s forgotten civilized doings,’ and I shoved the hat to him.

“‘Never mind,’ says he, waving his hand and smiling faintly, ‘get others,’ speaking to the boy alongside him.

“The old gentleman took one and touched his finger to the end of my cigar — it smoked as if the fire had been set to it.

“‘Waugh! the devil!’ screams I, darting back.

“‘The same!’ chimed in he, biting off the little end of his, and bowing, and spitting it out, ‘the same, sir.’

“‘The same! what?’

“‘Why — the devil.’

“‘H–l! This ain’t the hollow tree for this coon — I’ll be making medicine,’ so I offer my cigar to the sky and the earth like an Injun.

“‘You must not do that here — out upon such superstition,’ says he, sharp-like.

“‘Why?’

“‘Don’t ask so many questions — come with me,’ rising to his feet, walking off slowly and blowing his cigar-smoke over his shoulder in a long line, and I get alongside him. ‘I want to show you my establishment — you did not expect to find this down here, eh?’

“My breeches was all-fired stiff with the heat in the canyon, and my friend, seeing it, said, ‘Your breeches are tight; allow me to place my hand on them.’

“He rubbed his fingers up and down once, and by beaver, they got as soft as when I traded them from the Pi-Ute on the Gila.

“I now felt as brave as a buffalo in the spring. The old man was clever, and I walked alongside him like an old acquaintance. We soon stopped before a stone door and opened without touching.

“‘Here’s damp powder and no fire to dry it,’ shouts I, stopping.

“‘What’s the matter; do you not wish to perambulate through my possessions?’

“‘This hoss doesn’t say what the human for perambulating is, but I’ll walk plum to the hottest fire in your settlement if that’s all you mean.’

“The place was hot, and smelt of brimstone, but the darned screeching took me. I walk up to the other end of the lodge and steal my mule, if there wasn’t Jake Beloo, as trapped with me to Brown’s Hole! Many hell-cats were a-pulling at his ears, a-jumping on his shoulders, and swinging themselves to the ground by his long hair. Some ran hot irons into him, but when we came up, they went off in a corner, laughing and talking like wildcats’ gibberish on a cold night.

“Poor Jake! he came to the bar looking like a sick buffalo in the eye. The bones stuck through his skin, his hair was matted and long all over, just like a blind bull, and white blisters spotted him. ‘Hatch, old fellow! you here too? — how are you?’ says he, in a faint-like voice, staggering and catching on to the bar for support — ‘I’m sorry to see you here; what did you do?’ He raised his eyes to the older man standing behind me, who gave him such a look; he went howling and foaming at the mouth to the fur end of the den and fell down, rolling over the damp stones. The devil, who was chuckling by a furnace where irons were heating, approached easily and ran one into his back. I jumped at them and hollered, ‘You audacious little hell-pups, let him alone; if my scalp-taker were here, I’d make buzzard feed of your meat and parfleche of your dog-skins,’ but they squeaked out, to ‘go to the devil.’

“‘Waugh!’ says I, ‘if I ain’t pretty close to his lodge, I’m a n***er!’

“The old gentleman speaks up, ‘Take care of yourself, Mr. Hatcher,’ in a mighty soft kind voice, and he smiles so calm and devilish- it nigh froze me. If the ground would open with an earthquake and take me in, I’d be much obliged. Thinks I, ‘You saint-for-saken, infernal hell-chief, how I’d like to stick my knife in your withered old bread-basket.’

“‘Ah! My dear fellow, no use trying — that’s a decided impossibility.’ I jumped ten feet. I swear a medicine man couldn’t a-heard me, for my lips didn’t move, and how he knew is more than this hoss can tell.

“‘I see your nervous equilibrium is destroyed; come with me.’

“At the other side, the old gentleman told me to reach down for a brass knob. I thought a trick would be played on me, and I dodged.

“‘Do not be afraid; turn it when you pull; steady; that’s it.’ It came, and a door shut by itself.

“‘Mighty good hinges!’ said I, ‘don’t make any noise, and go shut without slamming and cussing them.’

“‘Yes — yes! Some of my importation. No, they were never made here.’

“It was dark at first, but there was too much light whenever the other door opened. In another room, there was a table in the middle, with two bottles and little glasses like them in St. Louis at the drink houses, only prettier. A soft, thick carpet was on the floor, and a square glass lamp hung from the ceiling. I sat cross-legged on the floor, and he on a sofa, his feet cocked on a chair and his tail coiled under him, comfortable as traders in a lodge. He hollered something I couldn’t make out, and in came two black crook-shanked devils with a round bench and a glass with cigars in it. They vamosed, and the old coon, inviting me to take a cigar, helped himself, and reared his head back, while I sorter lays on the floor, and we smoked and talked.

“‘But have we not been sitting long enough? Take a fresh cigar, and we will walk. That was Purgatory, where your quondam friend, Jake Beloo, is. He will remain there awhile longer, and, if you desire, it can go, though it cost much exertion to entice him here, and then only after he had drunk hard.’

“‘I wish you would, sir. Jake was as good a companion as ever trapped beaver or gnawed poor bull in the spring, and he treated his Indian wife as if she was a white woman.’

“‘For your sake, I will; we may see others of our acquaintance before leaving this,’ says he, sorter queer-like, as if to mean, no doubt of it.

“The door of the room we had been talking in shut of its own accord. We stooped, and he touched a spring in the wall; a trap door flew open, showing a flight of steps. He went first, cautioning me not to slip on the dark stairs, but I shouted not to mind me. I thanked him for telling me.

“We went down and down until I began to think the old cuss was going to get me safe too, so I sang out — ‘Hello! Which way; we must be mighty nigh under Wah-to-yah, we’ve been going on so long?’

“‘Yes,’ said he, much astonished, ‘we’re just under the Twins. Why, turn and twist you ever so much, you do not lose your reckoning.’

“‘Not by a long chalk! This child had his bringing-up at Wapakonnetta, and that’s a fact.’

“From the bottom, we went on in a dampish passage, gloomily lit with one candle. The grease was running down the block that had an auger hole bored in it for a candlestick, and the long snuff to the end was red, and the blaze clung to it as if it hated to part company and turned black and smoked at the point in mourning. The cold chills shook me, and the old gentleman kept so still, the echoes of my feet rolled back so solemn and hollow; I wanted liquor mighty bad!

“There was a noise smothered-like, and some poor fellow would cry out worse than Comanche a-charging. A door opened, and the old gentleman touched me on the back; I went in, and he followed. It flew too, and though I turned right around to look for a sign to escape, if the place got too hot, I couldn’t find it.

“‘What now, are you dissatisfied?’

“‘Oh, no! I was looking to see what sort of a lodge you have.’

“‘I understand you perfectly, sir; be not afraid.’

“My eyes were blinded in the light, but rubbing them, I saw two big snakes coming at me, their yellow and blood-shot eyes shining awfully, and their big red tongues darting backward and forwards, like a panther’s paw when he slaps it on a deer, and their jaws wide open, showing long, slim, white fangs. On my right, four ugly animals jumped at me and rattled their chains — I swear their heads were bigger than a buffalo’s in summer. The snakes hissed and showed their teeth and lashed their tails, and the dogs howled and growled and charged, and the light from the furnace flashed out brighter and brighter; and above me and around me, a hundred devils yelled and laughed and swore and spit, and snapped their bony fingers in my face, and leaped up to the ceiling into the black, long spider-webs, and rode on the spiders which were bigger than a powder-horn, and jumped onto my head. Then they all formed in line and marched, hooted, and yelled, and when the snakes joined the procession, the devils leaped on their backs and rode. Then some smaller ones rocked up and down on springing boards, and when the snakes came opposite, they darted way up in the air and dived down their mouths, screeching for scalps like so many Pawnee Indians. When the snakes were in front of us, the little devils came to the end of the snakes’ tongues, laughing and dancing and singing like idiots. Then the big dogs jumped clean over us, growling louder than a grizzly bear, and the devils, holding on to their tails, flopped over my head, screaming — ‘We’ve got you — we’ve got you at last!’

“I couldn’t stand it no longer, and shutting my eyes, I yelled right out and groaned.

“‘Be not alarmed,’ and my friend drew his fingers along my head and back and pulled a little narrow black flask from his pocket, with — ‘Here, take some of this.’

“I swallowed a few drops. It tasted sweetish and bitterish — I don’t exactly know how, but as soon as it was down, I jumped up five times and yelled, ‘Out of the way, you little ones, and let me ride’; and after running alongside, and climbing up his slimy scales, I got straddle of a big snake, who turned his head round, blowing his hot, sickening breath in my face. I waved my old wool hat and, kicking him into a fast run, sang out to the little devils to get up behind, and off we started, screeching, ‘Hurrah for Hell!’ The old gentleman rolled over and bent himself double, laughing till he pretty nigh choked. We kept going faster and faster till I got onto my feet, although the scales were mighty slippery and danced Injun, and whooped louder than them all.

“All at once, the old gentleman stopped laughing, pulled his spectacles down on his nose, and said, ‘Mr. Hatcher, we had better go now,’ and then he spoke something I couldn’t make out, and all the animals stood still; I slid off, and the little hell-cats, a-pinching my ears and pulling my beard, went off squealing. Then they all formed in a half moon before us — the snakes on their tails, with heads way up to the black cobwebbed roof, the dogs reared on their hind feet, and the little devils hanging everywhere. Then they all roared, hissed, screeched several times, and, wheeling off, disappeared just as the lights went out, leaving us in the dark.

“‘Mr. Hatcher,’ said the old gentleman again, moving off, ‘you will please amuse yourself until I return’, but seeing me look wild, he said, ‘You have seen too much of me feel alarmed for your safety. Take this imp for your guide, and if he is impertinent, put him through; and for fear, the exhibitions may overcome your nerves, imbibe of this cordial,’ which I did, and everything danced before my eyes, and I wasn’t a bit scared.

“I started for a red light that came through the crack of a door and stumbled over a three-legged chair as I pitched my last cigar stump to one of the dogs chained to the wall, who caught it in his mouth. When my guide opened the door, I saw a big blaze like a prairie fire, red and gloomy; and big black smoke was curling and twisting and spreading, and the flames a-licking the walls, going up to a point, and breaking into a wide blaze, with white and green ends. Bells were a-tolling, chains a-clinking, and mad howls and screams, but the old gentleman’s medicine made me feel as independent as a trapper with his animals feeding around him, two packs of beaver in camp, with traps sot for more.

“Close to the hot place was a lot of merry devils laughing and shouting, with an old pack of greasy cards — it reminded me of them we used to play with at the Rendezvous — shuffling them to the time of the Devil’s Dream, and Money Musk; then they’d deal in slow time, with the Dead March in Saul, whistling as solemn as medicine-men. Then they broke out sudden with Paddy O’Rafferty, which made this hoss move about in his moccasins so lively that one of them that was playing looked up and said, ‘Mr. Hatcher, won’t you take a hand? Make way, boys, for the gentleman.’

“Down I got amongst them but stepped on the tail of one little fellow leading the Irish jig. He hollered till I got off it, ‘Owch! But it’s on my tail ye are!’

“‘Pardon,’ said I, ‘but you are an Irishman!’

“‘No, indeed! I’m a hell-imp, he! He! who-oop! I’m a hell-imp,’ and he laughed and pulled my beard, and screeched till the rest threatened to choke him if he didn’t stop.

“‘What’s trumps?’ said I, ‘and whose deal?’

“‘Here’s my place,’ said one, ‘I’m tired of playing; take a horn,’ handing me a black bottle; ‘the game’s poker and it’s your next deal — there’s a bigger game of poker on hand’; and picking up an iron rod heating in the fire, he punched a miserable fellow behind bars, who cussed him and ran away into the blaze out of his reach.

“I thought I was great at poker by the way I gathered in the beaver skins at the Rendezvous, but here, the slick devils beat me without half trying. When they’d slap down a bully pair, they’d screech and laugh worse than trappers on a spree.

“Says one, ‘Mr. Hatcher, I reckon you’re a hoss at poker away in your country, but you can’t shine down here — you ain’t nowhere. That fellow looking at us through the bars was a preacher up in the world. When we first got him, he was all-fired hot and thirsty. We would dip our fingers in water and let it run in his mouth to get him to teach us the best tricks — he’s a trump; he would stand and stamp the hot coals and dance up and down while he told his experience. Whoop-ee! How he would laugh! He has delivered two long sermons on a Sunday and played poker on the night of five-cent antes with the deacons for the money bagged that day. When he was in debt, he urged the congregation to give more for the poor heathen in a foreign land, a-dying and losing their souls for want of a little money to send them a gospel preacher — that the poor heathen would be damned to eternal fire if they didn’t make up the dough. The gentleman that showed you around — old Sate, we call him — had his eyes on the preacher for a long time. When we got him, we had a barrel of liquor and carried him around on our shoulders until we were tired of the fun and threw him in the furnace yonder. We call him “Poke,” for that was his favorite game. Oh, Poke,’ shouted my friend, ‘come here; here’s a gentleman who wants to see you — we’ll give you five drops of water, and that’s more than your old skin’s worth.’

“He came close, and though his face was poor, and all scratched, and his hair singed mighty nigh off, make meat of this hoss, if it wasn’t old Cormon, that used to preach in the Wapakonnetta settlement! Many times, he’s made my hair stand on end when he preached about the other world. He came closer, and I could see the chains tied on his wrists, where they had worn to the bone. He looked a darned sight worse than if the Comanches had scalped him.

“‘Hello! Old coon,’ said I, ‘we’re both in that awful place you talked so much about, but I ain’t so bad off as you yet. This young gentleman,’ pointing to the devil who told me of his doings — ‘this gentleman has been telling me how you took the money you made us throw in on Sunday.’

“‘Yes,’ said he, ‘if I had only acted as I told others to do, I would not have been scorching here forever and ever — water! Water! John, my son, for my sake, a little water.’

“Just then, a little rascal stuck a hot iron into him, and off he ran in the flames, ‘caching’ on the cool side of a big chunk of fire, a-looking at us for water; but I cared no more for him than the Pawnee whose scalp was tucked in my belt for stealing my horses on Coon Creek; and I said:

“‘This hoss doesn’t care a cuss for you; you’re a sneaking hypocrite; you deserve all you’ve got and more too — and look here, old boy, it’s me that says so.’

“I strayed off a piece, pretending to get cool, but this hoss began to get scared, and that’s a fact, for the devils carried Cormon until they got tired of him, and, said I to myself, ‘Ain’t they been doing me the same way? I’ll cache, I will.’

“Well, now, I felt sort of queer, so I strolled along kind o’ slowly until I saw an open place in the rock, not minding the imps who were drinking away like trappers on a bust. It was so dark there that I felt mighty still, for I feared they’d be after me. I got almost to a streak of light when there was such an uproar in the cave that it gave me trembles. Doors were slamming, dogs growling and rattling their chains, and all the devils were screaming. They came charging; the snakes were hissing sharp and wiry; the beasts howled long and mournfully; thunder rolled up overhead, and the imps were yelling and screeching like they were mad.

“It was time to break for timber, sure, and I ran as if a wounded buffalo was raising my shirt with his horns. The place was damp, and in the narrow rock, lizards and vipers and copperheads jumped out at me and climbed on my legs, but I stamped and shook them off. Owls, too, flopped their wings in my face and hooted at me, and fire blazed out and lit the place up, and brimstone smoke came nigh choking me. Looking back, hell was coming; nothing but devils on devils filled the hole!

“I threw down my hat to run faster and then jerked off my old blanket, but still, they were gaining on me. I made one jump clean out of my moccasins. The giant snake in front was getting closer and closer, with his head drawn back to strike; then a hell-dog ran up nearly alongside, panting and blowing with the drool running out of his mouth and a lot of devils hanging on to him who was a-cussing me and screeching. I strained every joint, but it was useless; they still gained — not fast — but gaining. I jumped and swore, leaned down, and flung out my hands, but the dogs were nearer every time, and the horrid yelling and hissing way back grew louder and louder.

At last, a prayer mother used to make me say I hadn’t thought of for twenty years came right before me as clear as a powder horn. I kept running and saying it, and the devils held back a little. I gained some on them. I stopped repeating it to get my breath when the foremost dog lunged at me — I had forgotten it.

Turning my eyes, the old gentleman looked at me and kept alongside me without walking. His face wasn’t more than two feet off, and his eyes were fixed, steady, calm, and devilish. I screamed right out. I shut my eyes, but he was still there. I howled and spit and hit at it but couldn’t get his darned face away. A dog caught hold of my shirt with his fangs, and two devils, jumping on me, caught me by the throat, trying to choke me. While I was pulling them off, I fell, with about thirty-five of the infernal things and the dogs and the slimy snakes on top of me, a-mashing and tearing me. I bit pieces out of them, and bit again, and scratched and gouged. When I was ‘most give out, I heard the Pawnee scalp-yell, and use my rifle for a poking stick, if it didn’t charge a party of the best boys in the mountains. They slayed the devils right and left and set them running like goats, but this hoss was so weak fighting he fainted away. When I came to, I was on the Purgatoire, just where I found the liquor, and some trappers were slapping their ‘what’s’ in my face to bring me to. All around where I was laying, the grass was pulled up, the ground dug with my knife, and the bottle, cached when I traded with the Ute, was smashed to flinders against a tree.

“‘Why, what on earth, Hatcher, have you been doing here? You were kicking and tearing around and yelling as if your scalp was taken. We don’t understand these hifalutin notions.’

“‘The devils of hell was after me,’ said I, mighty gruff. ‘This hoss has seen more of them than he ever wants to see again.’

“They tried to get me out of the notion, but I swear, and I’ll stick to it, I saw a heap more of the all-fired place than I want to again. If it ain’t a fact, I don’t know a fat cow from the poor bull.”

With this declaration, Hatcher always ended his yarn, and you could never make him believe that he had only a touch of delirium tremens.

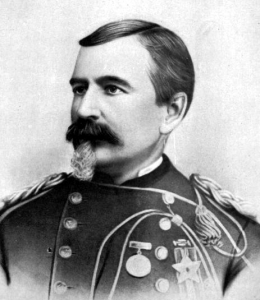

Colonel W. F. Cody related this story:

In 1864, two military expeditions were sent into the northwest country to disperse any hostile gatherings of Indians, one expedition starting from Fort Lincoln on the Missouri River under the command of General George A. Custer. On this expedition, Custer discovered gold in the Black Hills, which finally led up to the great Sioux War of 1876, when he lost his life in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The other expedition started from Rawlins on the Union Pacific Railway to go north into the Big Horn Basin in the Big Horn Mountain country. Colonel Anson Mills commanded this expedition. I was the chief scout and guide of the expedition.

One day, when we were on the Great Divide of the Big Horn Mountains, the command had stopped to let the pack train close up.

While we were resting there, several officers and I were talking to Colonel Mills when we noticed, coming from the direction we were going, a solitary horseman about three miles distant.

He was coming from the ridge of the mountains. The colonel asked me if I had any scouts in that direction, and I told him I had not. We naturally supposed that it was an Indian. He kept drawing nearer and nearer to us until we realized it was a white man, and as he came on, I recognized him as California Joe.

When he got within hailing distance, I sang, “Hello, Joe,” and he answered, “Hello, Bill.” I said: “Where in the world are you going to, out in this country?” (We were then about 500 miles from any part of civilization.) He said he was just out for a morning ride. I introduced him to the colonel and officers, who had all heard and read of him, for he had been made famous in Custer’s Life on the Plains. He was tall, about six feet three inches in his moccasins, with reddish-gray hair and whiskers, very thin, nothing but bone, ligament, and muscle. He was riding an old cayuse pony with an old saddle, a very old bridle, and a pair of elk-skin hobbles attached to his saddle, which also hung a piece of elk meat. He carried an old Hawkins rifle. He had an old, shabby army hat on, a ragged blue army overcoat, a buckskin shirt, and a pair of worn, greasy buckskin pants that reached only a little below his knees, having shrunk in the wet; he also wore a pair of old army government boots with the soles worn off. That was his make-up.

I remember the colonel asking him if he had succeeded in life. He pointed to the old cayuse pony, gun, and clothes and replied, “This is seventy years’ gathering.” Colonel Mills then asked him if he would have anything to eat; he said he had plenty to eat, and all he wanted was tobacco. Tobacco was scarce in the command, but they rounded him up sufficiently to do him that day. When invited to go with us, he said he was not particular about where he went; he would just as soon go one way as the other; he remained with us for several days and stayed the entire trip.

He greatly assisted me, as he knew the country thoroughly. He was a fine mountain guide, but I could seldom find him when I most needed him, as he was generally back with the column, telling frontier stories and yarns to the soldiers for a chew of tobacco.

One day, I rode back from the advance guard to ask the colonel how far he wanted to go before camping. While I was riding along talking to him, we noticed that the advance guard had stopped and was standing in a circle, evidently looking at something very intently. They were so interested that they did not come to their senses until the colonel and I rode in among them. Then they immediately moved forward, leaving the colonel and myself to see what they had been investigating. It was a lone grave in the desolate mountains, and whoever had been buried there evidently had friends because the spot was nicely covered with stones to prevent the wolves from digging up the corpse.

We were looking at this grave when old Joe rode up, and as he stopped, he threw his hat on the pile of rocks and said, “At last.”

The colonel said, “Joe, do you know anything about the history of this grave?”

Joe replied — “Well, I should think I did.”

The colonel then asked him to tell us about it.

Joe said: — “In 1816” — we didn’t stop to think how far back 1816 was — “I had been to Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River with a company of fur traders and had been trapping in that country for two or three years, and by that time the party had made up their minds they would start back to the States, across the mountains. They were headed for the Missouri River, and when they got there, they intended to build a boat and float down to St. Louis. As they were coming across the Continental Divide of the Rocky Mountains, had reached the eastern slope, and were coming down one of the tributaries of the Stinking Water, someone of the party discovered what he thought to be gold nuggets in the stream bed. The water was clear. Every man went down to the water prospecting. The stream was so full of gold nuggets that they all jumped off their horses, leaving them packed as they were, and began throwing them out on the banks.

“They abandoned everything they had with them, provisions and all, excepting their rifles, and prepared to load the gold.

“Then they started for the Missouri River again, and when they reached the spot where this grave was, a man was taken suddenly ill, died in a very few minutes, and they buried him there.”

Old Joe gave a sly wink as much as to say, “We buried the money with the man.”

At this time, quite several officers gathered around where the advance of the command had halted, and there may have been thirty or forty soldiers listening to this story; some took it to be one of Joe’s lies that he usually told for tobacco.

The colonel ordered the bugler to sound “forward.” The command moved on and, within five or six miles, went into camp. But every man who had listened to Joe’s story of this grave, feeling some $100,000 buried in it, gave it a look as they passed by.

We moved on and went into camp. Joe was messing with me, and after we had supper, he said, “Bill, would you like to see a little fun tonight?” I said, “Yes, tonight for fun or anything else.” He said, “As soon as it darkens, you follow me.” I said, “You bet I will follow you,” thinking all the time that he was going back to dig this fellow up.

As soon as it was dark, he started and motioned me to follow him, but instead of going back on the trail, he went in the direction we intended to go in the morning. I think, “That is good medicine; we won’t go directly back on the trail but follow another.”

I asked him if we did not want to take a pick and shovel, and he said, “What for?” I said, “We will need it.” He said, “No, we won’t need it; you come on.”

When we got outside the camp, he turned to the left, returning to our trail. I said, “This is all right.” He was now going back toward the grave. We went about a mile on the trail, and he said, “Sit down here.” I said, “Don’t we want to go on?” He said, “What for?” I said, “To dig that fellow up and get the money.” He said, “The money be damned; I never saw the bloomin’ grave before,” or something like that. I was disappointed. He said, “Wait a few minutes until after ‘taps,’ and you will see that camp empty itself.”

They came, scouts, soldiers, and packers by the dozen, sneaking through the brush and hurrying back on the trail. Old Joe laid down behind this boulder and just rolled with laughter to see them going to dig up the grave.

The next morning, the boys told me that they dug up the grave and found some bones; they dug up a quarter of an acre of ground and never got the color of a piece of gold; then they “tumbled.”

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Notes and Authors: This article was excerpted from the book The Great Salt Lake Trail, written by Colonel Henry Inman and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and first published in 1898. Inman was an officer in the U.S. Army and an author dealing with subjects of the Western plains. Buffalo Bill was a buffalo hunter, scout, and showman. The article that appears on these pages is not verbatim, as it has been edited for easier reading.

Also See:

Old West Explorers, Trappers, Traders & Mountain Men

Trading Posts and Their Stories