The Indian, seeing that he had missed, raised his hatchet and once more, shrugging his head in his blanket, and turning to look over his other shoulder, attempted to strike again, but the blow was evaded by a sudden toss of his intended victim’s head. Not satisfied with two abortive trials, the third attempt must be made to brain me, and repeating the same motions, with a great “Ugh!” he seemed to put all his strength into the blow, which, like the others, missed, and spent its force in the earth. By this time, the rescuing party had come near enough to prevent the savage from risking another effort. He then addressed the other Indians in Spanish, which I understood, saying, “We must run, or the Americans will kill us!” and loosening his grasp, he scampered off with his companions as fast as his legs could take him, hurried on by several pieces of lead fired from the old flintlocks of the traders.

By sundown, every man had returned to the desolate camp, but not an animal had been recovered. Then, with tired limbs and weary hearts, we took turns guarding the wagons through the long night. The next morning each man shouldered his rifle, and having had his proportion of the provisions and cooking utensils assigned him, we broke camp, and again turned to take a last look at the country behind us, in which we had experienced so much misfortune, and started on foot for our long march through the dangerous region ahead of us.

Scarcely had we gotten out of sight of our abandoned camp, when one of the party, happening to turn his eyes in that direction, saw a large volume of smoke rising in the vicinity; then we knew that all of our wagons, and everything we had been forced to leave, were burning up. This proved that, although we had been unable to discover any signs of Indians, they had been lurking around us all the time, and this fact warned us to exercise the utmost vigilance in guarding our persons.

Though our burdens were very heavy, the first few days were passed without anything to relieve the dreadful monotony of our wearisome march. Still, each succeeding 24 hours, our loads became visibly lighter, as our supplies were rapidly diminishing. It had already become apparent that even in the exercise of the greatest frugality, our stock of provisions would not last until we could reach the settlements, so some of the most expert shots were selected to hunt for game; but even in this, they were not successful, the very birds seeming to have abandoned the country in its extreme desolation.

After eight days of travel, despite our most rigid economy, an inventory showed that there were less than 100 pounds of flour left. The hunters repeated the same old story day after day: “No game!” For two weeks, the allowance of flour to each individual was but a spoonful, stirred in water, and taken three times a day.

However, fortune smiled upon the weary party; one of the hunters returned to camp with a turkey he had killed. It was soon broiling over a fire which willing hands had kindled, and our drooping spirits were revived for a while. While the turkey was cooking, a crow flew over the camp, and one of the company, seizing a gun, dispatched it, and in a few moments, it, too, was sizzling along with the other bird.

Now, in addition to the pangs of hunger, a scarcity of water confronted us, and one day we were compelled to resort to a buffalo-wallow and suck the moist clay where the huge animals had been stamping in the mud. We were much reduced in strength, yet each day added new difficulties to our sad situation. Some became so weak and exhausted that it was with the greatest effort they could travel at all. To divide the company and leave the more feeble behind to starve or be murdered by the merciless Indians was not considered for a moment. Still, one alternative remained, and that was speedily accepted. As soon as a convenient camping ground could be found, a halt was made, shelter established, and things made as comfortable as possible. Here the weakest remained to rest while some of the strongest scoured the surrounding country searching for game. During this temporary halt, the hunters were more successful than before, having killed two buffaloes in one morning besides some smaller animals. Again the dry natural fuel of the prairies was called into requisition, and a juicy steak was once more broiling over the fire.

With an abundance to eat and a few days’ rest, the whole company revived and were enabled to renew their march homeward. We were now in the buffalo range. Every day, the hunters were fortunate enough to kill one or more of the immense animals, thus keeping our larder in excellent condition and starvation averted.

Doubting whether our good fortune concerning food would continue for the remainder of our march and our money becoming very cumbersome, it was decided by a majority that at the first suitable place we came to, we would bury it and risk its being stolen by our enemies. When not more than half of our journey had been accomplished, we came to an island in the river to which we waded and there, between two large trees, dug a hole and deposited our treasure. We replaced the sod over the spot, taking the utmost precaution to conceal every sign of disturbing the ground. Though no Indians had been seen for several days, a sharp lookout was kept in all directions for fear that some lurking savage might have been watching our movements. This task finished, with much lighter burdens, but more anxious than ever, we again took up our march eastwardly and, thus relieved, were able to carry a greater quantity of provisions.

Having journeyed until we supposed we were within a few miles of the settlements, some of our number, scarcely able to travel, thought the best course to pursue would be to divide the company; one portion to press on, the weaker ones to proceed by easier stages, and when the advance arrived at the settlements, they were to send back relief for those plodding on wearily behind them. Soon a few who were stronger than the others reached Independence, Missouri, and immediately sent a party with horses to bring in their comrades; so, at last, all got safely to their homes.

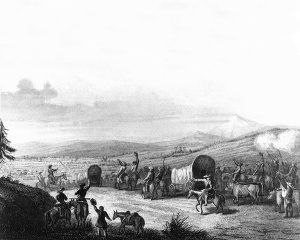

In the spring of 1829, Major Bennett Riley of the United States Army was ordered with four companies of the Sixth Regular Infantry to march out on the Trail as the first military escort ever sent to protect the caravans of traders going and returning between Western Missouri and Santa Fe. Captain Philip St. George Cooke of the Dragoons accompanied the command and kept a faithful journal of the trip. The official report of Major Riley to the Secretary of War, I have interpolated here copious extracts.

The journal of Captain Cooke states that the battalion marched from Fort Leavenworth, which was then called a cantonment, and, strange to say, had been abandoned by the Third Infantry on account of its unhealthiness. On June 5, Riley crossed the Missouri River, the cantonment, and re-crossed the river again at a point a little above Independence to avoid the Kansas River, which had no ferry.

After five days’ marching, the command arrived at Round Grove, where the caravan had been ordered to rendezvous and wait for the escort. The number of traders aggregated about seventy-nine men, and their train consisted of 38 wagons drawn by mules and horses, the former preponderating. At an average of 14 miles a day, five days’ marching brought them to Council Grove. Leaving the Grove, in a short time, Cow Creek was reached, which at that date abounded in fish; many of which, says the journal, “weighed several pounds, and were caught as fast as the line could be handled.” The captain does not describe the variety to which he refers; probably they were the buffalo–a species of sucker, to be found today in every considerable stream in Kansas.

Having reached the Upper Valley, bordered by high sandhills, the journal continues:

From the tops of the hills, we saw far away, in almost every direction, mile after mile of prairie, blackened with buffalo. One morning, when our march was along the natural meadows by the river, we passed through them for miles; they opened in front and closed continually in the rear, preserving a distance scarcely over three hundred paces. On one occasion, a bull had approached within two hundred yards without seeing us until he ascended the river bank; he stood a moment shaking his head and then charged at the column. Several officers stepped out and fired at him, two or three dogs also rushed to meet him. Still, right onward he came, snorting blood from mouth and nostril at every leap, and, with the speed of a horse and the momentum of a locomotive, dashed between two wagons, which the frightened oxen nearly upset; the dogs were at his heels, and soon he came to bay, and, with tail erect, kicked violently for a moment, and then sank in death–the muscles retaining the dying rigidity of tension.

The command arrived at its destination–Chouteau’s Island, then on the boundary line between the United States and New Mexico about the middle of July. Our orders were to march no further, and, as a protection to the trade, it was like the establishment of a ferry to the mid-channel of a river.

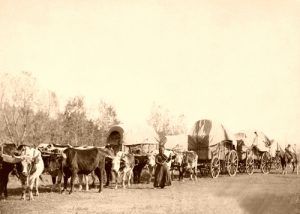

Up to this time, traders had always used mules or horses. Our oxen were an experiment that succeeded admirably; they even did better when water was very scarce, which is an important consideration.

A few hours after the departure of the trading company, as we enjoyed a quiet rest on a hot afternoon, we saw beyond the river several horsemen riding furiously toward our camp. We all flocked out of the tents to hear the news, for they were soon recognized as traders. They stated that the caravan had been attacked, about six miles off in the sandhills, by an innumerable host of Indians; that some of their companions had been killed; and they had run, of course, for help. There was not a moment’s hesitation; the word was given, and the tents vanished as if by magic. The oxen grazing nearby were speedily yoked to the wagons, and we marched into the river. Then I deemed myself the most unlucky of men; a day or two before, while eating my breakfast, with my coffee in a tin cup–notorious among chemists and campaigners for keeping it hot–it was upset into my shoe, and on pulling off the stocking, it so happened that the skin came with it. Being thus hors de combat, I sought to enter the combat on a horse, which was allowed; but I was put in command of the rear guard to bring up the baggage train. It grew late, and the wagons crossed slowly, for the river unluckily took that particular time to rise fast, and, before all were over, we had to swim it, and by moonlight. We reached the encampment at one o’clock at night. All was quiet and remained so until dawn when the pickets reported they saw several Indians moving off at the sound of our bugles. On looking around us, we perceived ourselves and the caravan in the most unfavorable defenseless situation possible–in the feet high and within gun-shot all around. There was the narrowest practicable entrance and outlet.

We ascertained that some mounted traders, despite all remonstrance and command, had ridden on in advance, and when in the narrow pass beyond this spot, had been suddenly beset by about 50 Indians; all fled and escaped save one, who, mounted on a mule, was abandoned by his companions, overtaken, and slain. The Indians, perhaps, equaled the traders in number, but notwithstanding their extraordinary advantage of the ground, dared not attack them when they made a stand among their wagons; and the latter, all well armed, were afraid to make a single charge, which would have scattered their enemies like sheep.

Having buried the poor fellow’s body and killed an ox for breakfast, we left this sand hollow, which would soon have been roasting hot, and advancing through the defile–of which we took care to occupy the commanding ground–proceeded to escort the traders at least one day’s march further.

When the next morning broke clear and cloudless, the command was confronted by one of those terrible hot winds, still frequent on the plains. The oxen with lolling tongues were incapable of going on; the train was halted, and the suffering animals unyoked, but they stood motionless, making no attempt to graze. Late that afternoon, the caravan pushed on for about 10 miles, where was the sandy bed of a dry creek, and fortunately, not far from the Trail, up the stream, a pool of water and an acre or two of grass was discovered. On the water’s surface floated thick the dead bodies of small fish, which the intense heat of the sun that day had killed.

Arriving at this point, it was determined to march no further into the Mexican territory. At the first light next day, we were in motion to return to the river and the American line, and no further adventure befell us.

While permanently encamped at Chouteau’s Island, situated in the Arkansas River, the term of enlistment of four of the soldiers of Captain Cooke’s command expired, and they were discharged. In his journal, he says:

Contrary to all advice, they determined to return to Missouri. After having marched several hundred miles over a prairie country, being often on high hills commanding a vast prospect, without seeing a human being or a sign of one, and, save the trail we followed, not the slightest indication that the country had ever been visited by man, it was exceedingly difficult to credit that lurking foes were around us, and spying our motions. It was so with these men; and being armed, they set out on August 1 on foot for the settlements. That same night three of the four returned. They reported that, after walking about 15 miles, they were surrounded by thirty mounted Indians. A wary old soldier of their number succeeded in extricating them before any hostile act had been committed; but one of them, highly elated and pleased at their forbearance, insisted on returning among them to give them tobacco and shake hands. In this friendly act, he was shot down. The Indians stripped him in an incredibly short time, and as quickly dispersed to avoid a shot; and the old soldier, after cautioning the others to reserve their fire, fired among them, and probably with some effect. Had the others done the same, the Indians would have rushed upon them before they could have reloaded. They managed to make good their retreat in safety to our camp.

We were instructed to wait here for the return of the caravan, which was expected early in October. Our provisions consisted of salt and half rations of flour, besides a reserve of 15 days’ full rations–as to the rest, we were dependent upon hunting. When the buffalo became scarce, or the grass bad, we marched to other ground, thus roving up and down the river for eighty miles. The first thing we did after camping was to dig and construct, with flour barrels, a well in front of each company; water was always found at the depth of from two to four feet varying with the corresponding height of the river, but clear and cool. Next, we would build sod fire-places; these, with network platforms of buffalo hide, used for smoking and drying meat, formed a tolerable additional defense, at least against mounted men.

Hunting was a military duty, done by detail, parties of 15 or 20 going out with a wagon. Completely isolated, and beyond support or even communication, in the midst of many thousands of Indians, the utmost vigilance was maintained. Officer of the guard every fourth night; I was always awake and generally in motion the whole time of duty. Night alarms were frequent; when, as we all slept in our clothes, we were accustomed to assembling instantly, and with scarcely a word spoken, take our places in the grass in front of each face of the camp, where, however wet, we sometimes lay for hours.

While encamped a few miles below Chouteau’s Island, on August 11, an alarm was given, and we were under arms for an hour until daylight. During the morning, Indians were seen a mile or two off, leading their horses through the ravines. A captain, however, with 18 men was sent across the river after buffalo, which we saw half a mile distant. In his absence, a large body of Indians came galloping down the river as if to charge the camp, but the cattle were secured in good time. A company, of which I was lieutenant, was ordered to cross the river and support the first. We waded in some disorder through the quick-sands and current, and just as we neared a dry sandbar in the middle, a volley was fired at us by a band of Indians, who that moment rode to the water’s edge. The balls whistled very near, but without damage; I felt an involuntary twitch of the neck, and wishing to return the compliment instantly, I stooped down, and the company fired over my head, with what execution was not perceived, as the Indians immediately retired out of our view. This had passed in half a minute, and we were astonished to see, a little above, among some bushes on the same bar, the party we had been sent to support, and we heard that they had abandoned one of the hunters, who had been killed. We then saw, on the bank we had just left, a formidable body of the enemy in close order, and hoping to surprise them, we ascended the bed of the river. In crossing the channel we were up to the arm-pits, but when we emerged on the bank, we found that the Indians had detected the movement, and retreated. Casting eyes beyond the river, I saw a number of the Indians riding on both sides of a wagon and team which had been deserted, urging the animals rapidly toward the hills. At this juncture, the adjutant sent an order to cross and recover the body of the slain hunter, who was an old soldier and a favorite. He was brought in with an arrow still transfixing his breast, but his scalp was gone.

On October 14, we again marched on our return. Soon after, we saw smoke rise over the distant hills; evidently, signals, indicating to different parties of Indians our separation and march, but whether preparatory to an attack upon the Mexicans or ourselves or rather our immense drove of animals, we could only guess.

Our march was constantly attended by great collections of buffalo, which seemed to have a general muster, perhaps for migration. Sometimes a hundred or two–a fragment from the multitude–would approach within two or three hundred yards of the column and threaten a charge which would have proved disastrous to the mules and their drivers.

Under the friendly cover of the shades of evening, on November 8, our ragged veterans marched into Fort Leavenworth and took quiet possession of the miserable huts and sheds left by the Third Infantry in the preceding May.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2021.

Also See:

Famous Men of the Santa Fe Trail

Indian Terrors on the Santa Fe Trail

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

About the Author: Excerpted from the book, The Old Santa Fe Trail, by Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Note: The text is not verbatim, as minor edits have been made throughout the tale. Henry Inman was well known both as an officer in the U.S. Army and an author dealing with subjects of the Western plains. During the Civil War, Inman was a Lieutenant Colonel, and afterward, he won distinction as a magazine writer. He wrote several books including his Old Santa Fe Trail, Great Salt Lake Trail, The Ranch on the Ox-hide, and other similar books dealing with the subjects he knew so well. Colonel Inman left a number of unfinished manuscripts at his death in Topeka, Kansas on November 13, 1899.