Located in Beaver County, Utah, is the silent remains of the once-booming mining camp of Frisco. Though its life was short, it is filled with history, from millions of dollars in ore taken from the Horn Silver Mine to shoot-outs in its dusty streets. Today its crumbling foundations, charcoal ovens, and silent cemetery speak eloquently of its rich and varied past.

Frisco’s story started with two prospectors by James Ryan and Samuel Hawks in September 1875. The pair worked at the Galena Mine in the San Francisco Mining District, which embraced approximately seven square miles on both flanks of the San Francisco Mountains. One day while on their way to work, they stopped to test a large outcropping for ore. When they found a solid ore body, they immediately staked a claim. Fearing that the mineral body was not very large, they decided to sell their claim rather than work it. Sadly for Ryan and Hawks, the new owners extracted some 25,000 tons of ore with high silver content by the end of the 1870s.

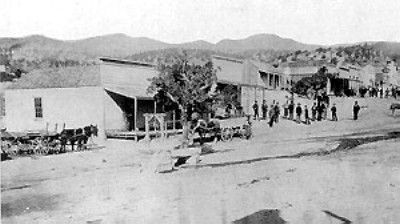

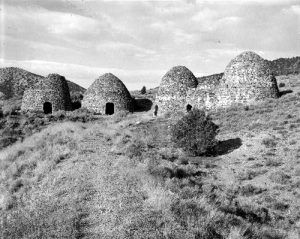

Near the mine, the town of Frisco soon sprouted up, named for the San Francisco Mountains. Another mine called the Horn Silver Mine was also discovered in 1875 and would soon become the largest producer in the area. With the success of the Horn Silver Mine, the Frisco Mining and Smelting Company expanded its workings in July 1877 by constructing a smelter that included five beehive charcoal kilns. Frisco soon developed as the post office and commercial center for the district and the terminus of the Utah Southern Railroad extension from Milford, some fifteen miles to the east.

Other mines located in the district included the Blackbird, Cactus, Carbonate, Comet, Imperial, King David, Rattler, and Yellow Jacket, but the Silver Horn was the largest.

By 1879 the United States Annual Mining Review and Stock Ledger were calling the Silver Horn Mine “the richest silver mine in the world now being worked.” Frisco was bustling, and on June 23, 1880, the Utah Southern Railroad Extension steamed into town, allowing the mines the opportunity for less expensive shipping.

Though there were several roaring mining camps in the San Francisco district, Frisco soon became the wildest. Like many boomtowns, its streets were lined with over twenty saloons, gambling dens, and brothels. Reaching a peak population of nearly 6,000, vice and crime became prevalent in the town. One writer described it as “Dodge City, Tombstone, Sodom, and Gomorrah all rolled into one.”

Murders were said to have been so frequent that city officials contracted to have a wagon pick up the bodies and take them to boot hill for burial. Eventually, a lawman from Pioche, Nevada, was hired and given free rein to “clean up the town.” When the tough marshal appeared on the scene, he allegedly told the town that he had no intention of making arrests or building a jail. Instead, the lawless element had two options – get out of town or get shot. Some of the wicked did not take the new marshal seriously as he reportedly killed six outlaws on his first night in town. After that, most of the lawless moved on, and Frisco became a milder place for its citizens.

On the morning of February 12, 1885, when the miners reported for duty, they were told to wait as tremors were shaking the ground. Taking precautions, as several cave-ins had previously occurred, the night shift came to the surface, and the day crew waited. Within minutes a massive cave-in occurred, collapsing tunnels down to the seventh level and shutting off the wealthiest part of the mine. The cause of the collapse was blamed on inadequately timbered tunnels bearing the tremendous weight of the rain and snow-soaked ground above. The collapse was so great that the cave-in was felt as far away as Milford, where some windows were reportedly broken. Fortunately, no one was killed, but the cave-in spelled the eventual demise of Frisco.

By 1885 over $60,000,000 in zinc, copper, lead, silver, and gold had been hauled away from Frisco by mule train and the Utah Southern Railroad. After the mine collapse, it began to produce again within a year, but never on the scale of its fabulous past.

By the turn of the century, only 14 businesses were still alive in Frisco, and its population had declined to 500. By 1912, only twelve businesses existed in the dwindling town of 150. By the 1920s, Frisco was a ghost town.

In 1982, Frisco’s kilns were placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2002, a mining company began to rework the mines of Frisco, so only the charcoal kilns and cemetery are accessible today. Frisco, Utah, is just off route 21, 15 miles west of Milford.

Ruins in Frisco, Utah courtesy Wikipedia.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of Utah

Silver Mining in the United States