By John S.C. Abbott in 1874

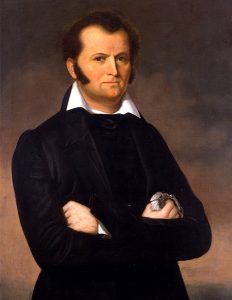

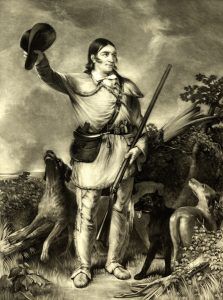

David Crockett

The fortress of the Alamo once stood just outside of the town of Bexar, on the San Antonio River. The town is about 140 miles from the coast and contained, at that time, about 1,200 inhabitants. Nearly all were Mexicans, though there were a few American families. In 1718, the Spanish Government had established a military outpost here; in 1721, a few emigrants from Spain commenced a flourishing settlement at this spot. Its site is beautiful, the air healthy, the soil highly fertile, and the water of crystal purity.

The town of Bexar subsequently received the name of San Antonio. On December 10, 1835, the Texans captured the town and citadel from the Mexicans. These Texan Rangers were rude men who had but little regard for the refinements or humanities of civilization. When David Crockett and his companions arrived, Colonel James Bowie, of Louisiana, one of the most desperate Western adventurers, was in the fortress. The celebrated bowie-knife was named after this man. There was but a feeble garrison, and it was threatened with an attack by an overwhelming force of Mexicans under General Antonio López de Santa Anna. Colonel William Travis was in command. He was happy to receive even so small reinforcement. As one of the bravest of men, the fame of Colonel David Crockett had already reached his ears.

“While we were conversing,” wrote Crockett, “Colonel Bowie had occasion to draw his famous knife, and I wish I may be shot if the bare sight of it wasn’t enough to give a man of a squeamish stomach the colic. He saw I was admiring it and said he, ‘Colonel, you might tickle a fellow’s ribs a long time with this little instrument before you’d make him laugh.'”

According to Crockett’s account, many shameful orgies took place in the little garrison. They were evidently in considerable trepidation, for a large force was gathering against them, and they could not look for any considerable reinforcements from any quarter. Rumors were continually reaching them of the formidable preparations Santa Anna was making to attack the place. Scouts were bringing in the news that Santa Anna, President of the Mexican Republic, was within six miles of Bexar at the head of 1,600 soldiers and accompanied by several of his ablest generals. It was said that he was doing everything in his power to enlist the warlike Comanche in his favor, but that they remained faithful in their friendship to the United States.

Early in February 1836, the army of Santa Anna appeared before the town, with infantry, artillery, and cavalry. They approached with military precision, their banners waving and their bugle notes bearing defiance to the feeble little garrison. The Texan invaders, seeing that they would soon be surrounded, abandoned the town to the enemy and fled to the protection of the citadel. They were but one hundred and fifty in number. Almost without exception, they were hardy adventurers and the most fearless and desperate of men. They had previously stored away in the fortress all the provisions, arms, and ammunition, of which they could avail themselves. Over the battlements, they unfurled an immense flag of thirteen stripes, and with a large white star of five points, surrounded by the letters “Texas.” As they raised their flag, they gave three cheers, while with drums and trumpets, they hurled back their challenge to the foe.

The Mexicans raised over the town a blood-red banner. It was their significant intimation to the garrison that no quarter was be expected. In the afternoon, Santa Anna, having advantageously posted his troops, sent a summons to Colonel Travis, demanding an unconditional surrender, threatening, in case of refusal, to put every man to the sword. The only reply Colonel Travis made was to throw a cannon-shot into the town. The Mexicans then opened fire from their batteries, but without doing much harm.

In the night, Colonel Travis sent the old pirate on an express to Colonel Fanning, who, with a small military force, was at Goliad, to entreat him to come to his aid. Goliad was about four days march from Bexar. The next morning the Mexicans renewed their fire from a battery about three hundred and fifty yards from the fort. A three-ounce ball struck the juggler on the breast, inflicting a painful but not a dangerous wound.

Day after day, this storm of war continued. The walls of the citadel were strong, and the bombardment inflicted but minor injury. The sharpshooters within the fortress struck down many of the assailants at great distances.

“The bee-hunter,” wrote Crockett, “is about the quickest on the trigger and the best rifle shot we have in the fort. I have already seen him bring down eleven of the enemy and at such a distance that we all thought that it would be a waste of ammunition to attempt it.” Provisions were becoming scarce, and the citadel was so surrounded that the garrison couldn’t cut its way through the lines and escape.

On February 28, Crockett wrote in his Journal:

“Last night, our hunters brought in some corn and had a brush with a scout from the enemy beyond gunshot of the fort. They put the scout to flight and got in without injury. They bring accounts that the settlers are flying in all quarters, in dismay, leaving their possessions to the mercy of the ruthless invader, who is literally engaged in a war of extermination more brutal than the untutored savage of the desert could be guilty of. Slaughter is indiscriminate, sparing neither sex, age, nor condition. Buildings have been burnt down, farms laid waste, and Santa Anna appears determined to verify his threat and convert the blooming paradise into a howling wilderness. For just one fair crack at that rascal, even at a hundred yards’ distance, I would bargain to break my Betsey and never pull the trigger again. My name’s not Crockett if I wouldn’t get glory enough to appease my stomach for the remainder of my life.”

“The scouts report that a settler by the name of Johnson, flying with his wife and three little children, when they reached the Colorado River, left his family on the shore and waded into the river to see whether it would be safe to ford with his wagon. When about the middle of the river, he was seized by an alligator, and after a struggle, was dragged under the water and perished. The helpless woman and her babes were discovered, gazing in agony on the spot, by other fugitives, who happily passed that way, and relieved them. Those who fight the battles experience but a small part of the privation, suffering, and anguish that follow in the train of ruthless war. The cannonading continued at intervals throughout the day, and all hands were kept up to their work.”

The next day he wrote:

“I had a little sport this morning before breakfast. The enemy had planted a piece of ordnance within gunshot of the fort during the night, and the first thing in the morning, they commenced a brisk cannonade, point-blank against the spot where I was snoring. I turned out pretty smart and mounted the rampart. The gun was charged again; a fellow stepped forth to touch her off, but before he could apply the match, I let him have it, and he keeled over.”

“A second stepped up, snatched the match from the hand of the dying man, but the juggler, who had followed me, handed me his rifle, and the next instant, the Mexican was stretched on the earth beside the first. A third came up to the cannon. My companion handed me another gun, and I fixed him off in like manner. A fourth, then a fifth, seized the match, who both met with the same fate. Then the whole party gave it up as a bad job and hurried off to the camp, leaving the cannon ready charged where they had planted it. I came down, took my bitters, and went to breakfast.”

In a week, the Mexicans lost 300 men. But, still, reinforcements were continually arriving so that their numbers were on the rapid increase. The garrison no longer cherished any hope of receiving aid from abroad.

On March 4th and 5th, 1836, we have the last lines that Crockett ever penned.

“March 4. Shells have been falling into the fort like hail during the day but without effect. About dusk, in the evening, we observed a man running toward the fort, pursued by about half a dozen of the Mexican cavalry. The bee-hunter immediately knew him to be the old pirate, who had gone to Goliad, and, calling to the two hunters, he sallied out of the fort to the relief of the old man, who was hard-pressed. I followed close after. Before we reached the spot, the Mexicans were close on the heels of the old man, who stopped suddenly, turned short upon his pursuers, discharged his rifle, and one of the enemies fell from his horse. The chase was renewed, but finding that he would be overtaken and cut to pieces, he now turned again and, to the amazement of the enemy, became the assailant in his turn. He clubbed his gun and dashed among them like a wounded tiger, and they fled like sparrows.

By this time, we reached the spot and, in the ardor of the moment, followed some distance before we saw that another detachment of cavalry cut off our retreat to the fort. Nothing was to be done but fight our way through. We were all of the same mind. ‘Go ahead!’ cried I, and they shouted, ‘Go ahead, Colonel!’ We dashed among them, and a bloody conflict ensued. They were about twenty in number, and they stood their ground. After the fight had continued about five minutes, a detachment was seen issuing from the fort to our relief, and the Mexicans scampered off, leaving eight of their comrades dead upon the field. But we did not escape unscathed, for both the pirate and the bee-hunter were mortally wounded, and I received a saber-cut across the forehead. The old man died without speaking as soon as we entered the fort. We bore my young friend to his bed, dressed his wounds, and I watched beside him. He lay, without complaint or manifesting pain, until about midnight, when he spoke, and I asked him if he wanted anything. ‘Nothing,’ he replied but drew a sigh that seemed to rend his heart as he added, ‘Poor Kate of Nacogdoches.’ His eyes were filled with tears, as he continued, ‘Her words were prophetic, colonel,” and then he sang in a low voice that resembled the sweet notes of his own devoted Kate:

‘But toom cam’ the saddle, all bluidy to see, And hame came the steed, but hame never came he.’

He spoke no more, and a few minutes after, died. Poor Kate, who will tell this to thee?

The romantic bee-hunter had a sweetheart by the name of Kate in Nacogdoches. She seems to have been a very affectionate and religious girl. In parting, she had presented her lover with a Bible, and in anguish of spirit had expressed her fears that he would never return from his perilous enterprise.

The next day, Crockett simply wrote, “March 5. Pop, pop, pop! Bom, bom, bom! throughout the day. No time for memorandums now. Go ahead! Liberty and Independence forever.”

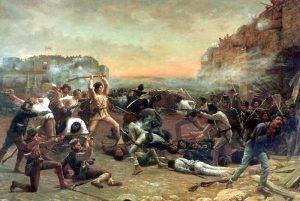

Before daybreak on March 6, the citadel of the Alamo was assaulted by the whole Mexican army, then numbering about three thousand men. Santa Anna in person commanded. The assailants swarmed over the works and into the fortress. The battle was fought with the utmost desperation until daylight.

Only six of the Garrison then remained alive. They were surrounded, and they surrendered. Colonel Crockett was one. He at the time stood alone at an angle of the fort, like a lion at bay. His eyes flashed fire, his shattered rifle in his right hand, and in his left a gleaming bowie-knife streaming with blood. His face was covered with blood flowing from a deep gash across his forehead. About twenty Mexicans, dead and dying, were lying at his feet. The juggler was also there dead. With one hand, he was clenching the hair of a dead Mexican, while with the other, he had driven his knife to the haft in the bosom of his foe.

Alamo Defenders Memorial in San Antonio, Texas courtesy Wikipedia.

The Mexican General Castrillon, to whom the prisoners had surrendered, wished to spare their lives. He led them to that part of the fort where Santa Anna stood surrounded by his staff. As Castrillon marched his prisoners into the presence of the President, he said:

“Sir, here are six prisoners I have taken alive. How shall I dispose of them?”

Santa Anna seemed much annoyed and said, “Have I not told you before how to dispose of them? Why do you bring them to me?”

Immediately several Mexicans commenced plunging their swords into the bosoms of the captives. Crockett, entirely unarmed, sprang, like a tiger, at the throat of Santa Anna. But before he could reach him, a dozen swords were sheathed in his heart, and he fell without a word or a groan. But there remained upon his brow the frown of indignation, and his lip was curled with a smile of defiance and scorn.

And thus was terminated the earthly life of this extraordinary man.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

About the Author: Excerpted from the book David Crockett: His Life and Adventures, written by John Stevens Cabot Abbott and published by Dood, Mead & Co, New York in 1874. Abbott was an American historian, pastor, and writer, who published several other historical and religious books during his lifetime. However, the text as it appears here is not verbatim as it has been edited for clarity and ease of the modern reader.

Also See:

David “Davy” Crockett – Frontier Hero

Mission San Antonio de Valero – The Alamo