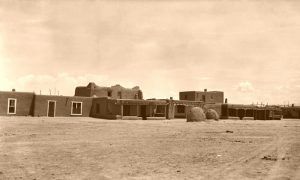

San Ildefonso Pueblo Mission, New Mexico, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

San Ildefonso Pueblo in north-central New Mexico is a Tewa-speaking pueblo built in about 1300. The ancestors of today’s Pueblo people originally lived at Mesa Verde, Colorado, and Bandelier, New Mexico. These Ancient Puebloans (Anasazi) thrived at Bandelier for years before moving down into the Rio Grande’s valleys after a prolonged drought. The San Ildefonso Pueblo people call their home Po-Woh-Geh-Owingeh, which means “Where the water cuts through.”

Located at the foot of Black Mesa, about 24 miles north of Santa Fe, the pueblo is characterized by its adobe buildings, ceremonial kivas, a central plaza, and a replica of the mission period church.

When the people moved from Bandelier, they established several communities in the Española Basin, where they hunted, grew a variety of crops using dryland farming techniques, and maintained connections with other communities in the region.

Contact with the Spanish began long before the missionaries arrived. Caspar Castaño de Sosa first visited the Pueblo of San Ildefonso in 1591. Two other Spaniards, Antonio Gutierrez de Umana and Francisco Leyba de Bonilla, led an unauthorized expedition into New Mexico in 1595 and spent a year among the northern pueblos making San Ildefonso their principal headquarters. In 1598, Juan de Oñate visited and named the pueblo San Ildefonso. Shortly after Oñate arrived, the village was relocated to its present site, and a convento and church were reportedly in use. Later around 1610, Fray Andrés Bautista established the first permanent mission, situated on the pueblo’s northwest side.

Spanish colonialism placed several burdens on the Tewa-speaking people of Northern New Mexico. Part of the Spanish colonial policy was to require tribute from Pueblo communities, and the Franciscan missionaries wanted the people to convert to Catholicism. After several decades these demands became too burdensome, and the Pueblo people resisted. The San Ildefonso Indians played a major role in the great Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Their chief, Francisco, was one of the major leaders of the rebellion that successfully drove the Spanish out of the region for a number of years. The two resident missionaries at San Ildefonso were killed and a number of Spanish settlers, and the church was destroyed during the revolt.

La Capilla de la Familia Sagrada Chapel and cemetery at the base of Black Mesa on the San Ildefonso Pueblo Reservation. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

In October 1692, Spanish forces led by General Diego de Vargas reconquered the area and obtained a promise from the people of San Ildefonso to keep the peace and submit to the Spanish authority.

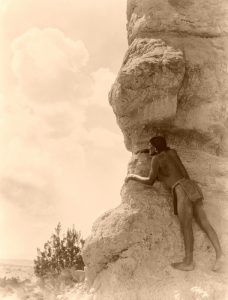

San Ildefonso’s resistance continued, however. The following year, the San Ildefonso Indians entrenched themselves on Black Mesa near San Ildefonso and most of the other Tewa groups and Tano people. In January 1694, Vargas returned to find the Tewa and Tano groups secure on the nearby mesa. He set out from Santa Fe to storm the mesa on February 25, with 60 fully armed soldiers, 30 militia, and some Indian allies from the Pecos Pueblo. After a series of unsuccessful attacks, he returned to Santa Fe on March 19. San Ildefonso had been a key supplier of grains, and the Spanish sorely needed that steady food supply as they reestablished their settlements. Vargas marched again on September 4th with all his available forces to remove the Tewa and Tano from San Ildefonso’s mesa. By holding the fields planted in the river valley, Vargas starved the defenders of the mesa into compliance, but the campaign took nine months and much of his military resources. The Franciscan Fray Francisco Cornera assumed his duties following the campaign at San Ildefonso on October 5, 1694.

A drought and bad winter in 1695 brought starvation and weakened the Spanish colonists. Seizing the opportunity, some pueblos rebelled again in 1696. The Franciscan priests Fray Antonio Moreno and Francisco Cornera were killed when the people of San Ildefonso destroyed the church convento a second time. Vargas quickly put down this revolt and reestablished the mission. In 1706, Fray Juan Alvarez recorded that the church was being rebuilt, and this building lasted into the 19th century.

The Pueblo of San Ildefonso was significantly affected by the intrusion of Spanish colonists. By the 1760s, the encroachments were so serious some San Ildefonso families reported that they had no agricultural lands to support themselves. Part of the disputed lands were restored to San Ildefonso by a 1786 decision of Governor Juan Bautista de Anza. Mexico took control of the area in 1821, and later the United States gained control in 1848 following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Congress created the modern reservation in 1858, confirming a grant of 17,292 acres of land to the pueblo, and the grant was patented in 1864. Today the San Ildefonso Pueblo is a self-governing federally recognized tribe.

The third mission church lasted for many years. Built from adobe, it had large buttresses, 20 x 20 feet at the base, and a bell tower. The church had a unique convent with a large “porter’s lodge” 41 feet square with an adobe bench that went all the way around the inside. This building, however, became unusable in the late 19th century with a badly leaking roof. The community debated whether to repair the church or construct a new one. In 1905, a new peaked tin-roof church was built, but it only lasted until the late 1950s. An interest in building a replica of the 1711 church led to a community effort from 1958-1968 to build the new adobe church, which was dedicated in December 1968.

In the meantime, the Pueblo people revived many of their pottery traditions and became famous for its matte and polished black-on-black pottery popularized in the early 20th century by Maria and Julian Martinez.

Today, San Ildefonso Pueblo is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It consists of over 60,000 acres and has an enrollment of approximately 750 people. A federally recognized tribe, San Ildefonso’s people have a strong sense of identity and retain ancient ceremonies, rituals, and tribal dances.

Primarily an artist community today, the pueblo welcomes visitors. Artisans at San Ildefonso have built upon and expanded from the traditions revived by Maria Martinez in the early 20th century. The pueblo’s feast day is January 23, where the traditional dances are performed, which are open to the public. Other dances open to the public include Corn Dance, which occurs in the early to mid-part of September, and dances at Easter. In addition to visiting Mission San Ildefonso, visitors can stop by the visitor center, shops, and the museum that displays Martinez’s work.

San Ildefonso Pueblo is south of Española, New Mexico, on NM 502. The pueblo can be visited daily for a fee. An additional fee is charged for photography.

More Information:

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander, updated April 2019.

Also See:

Ancient Cities of Native Americans

Ancient Puebloans of the Southwest

Pueblo Indians – Oldest Culture in the U.S.

Sources: