~~

An indigenous Native American people, the Washoe originally lived around Lake Tahoe and adjacent areas of the Great Basin. Their tribe name derives from the Washoe word, waashiw (wa·šiw), meaning “people from here.”

Semi-sedentary hunters and gatherers, their territory extended from the western slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains to areas as far east as Pyramid Lake in Nevada, including Lake Tahoe and the upper valleys of the Truckee, Carson, and West Walker Rivers. Traditionally, they would spend their summers in the Sierra Nevadas, the autumn in the ranges to the east, and winter and spring in the valleys in between. Their food base consisted primarily of pinyon pine nuts, roots seeds, berries, and game.

Family was and is the core of the Washoe because these are the people that lived and worked together and relied on each other. In the past, families are recorded as rarely fewer than five individuals and only occasionally exceeding twelve in size. A family was often a married couple and their children, but there were no distinct rules about how marriages and families should be formed and households were regularly made up of the parents of a couple, the couple’s siblings and their children, more than one husband or wife, or non-blood related friends.

Generally, a family was distinguished by whoever lived together in the winter house. Winter camps were usually composed of four to ten family groups living a short distance from each other. These family groups often moved together throughout the year. The Washoe practiced sporadic leadership, so at times, each group had an informal leader that was usually known for his or her wisdom, generosity, and truthfulness. He or she may possess special powers to dream of when and where there was a large presence of rabbit, antelope and other game, including the spawning of the fish, and would assume the role of “Rabbit Boss” or “Antelope Boss to coordinate and advise communal hunts.

The Washoe were traditionally divided into three groups, the northerners or Wel mel ti, the Pau wa lu who lived in the Carson Valley in the east, and the Hung a lel ti, who lived in the south. These three groups each spoke a slightly different yet distinct variant of the Washoe language. These groups came together throughout the year for special events and gatherings. Individual families, groups, or regional groups, came together at certain times to participate in hunting drives, war, and special ceremonies. During their yearly gathering at Lake Tahoe, each of the three regional groups camped at their family campsites at the lake. A person might switch from the group that they were born into to a group from another side of the lake. There were often cross-group marriages, sometimes even between the Paiute and the California tribes.

Relations with other tribes bordering Washoe territory were mostly about tolerance and mutual understanding. Sometimes events lead to tensions and warfare. It was beneficial to both sides to keep their distance, but they also needed to maintain a relationship to exchange trade goods.

They were first driven into the area from the east by their long-time enemies, the Northern Paiute, by whom they were later dominated. After soundly defeating the Washoe, the Paiute, who had obtained and learned to ride horses, would not allow the Washoe to own or ride their own mounts.

When white trappers and explorers began to make their way into their territory, the Washoe did their best to avoid them. They had heard about the new intruders before they ever saw one. As the Spanish invaded the California coast to establish missions and convert Indians to Catholicism, the Washoe began to make fewer and fewer trips to the west coast until eventually, those trips stopped altogether. Neighboring tribes that escaped into hiding in the high mountains probably warned the Washoe about the invaders.

Although White historians have concluded that the Spanish never entered Washoe territory, the Washoe have told stories about them for generations, and some Washoe words, including names for relatively new additions to the Washoe world, like horse, cow, and money, are similar to the Spanish terms.

John C. Fremont

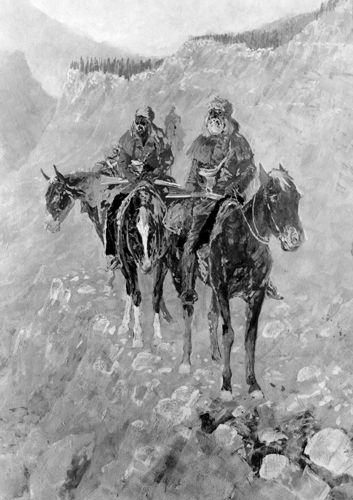

When the first white fur traders and surveyors began to enter Washoe territory the Indians approached the newcomers with caution. They preferred to observe the intruders from a distance. The first written record of non-Indians in Washoe Land were fur trappers in 1826; they may have met the Washoe, but left no description of the encounter. The first written description of the Washoe was by John Charles Fremont in 1844, who was leading a government surveying expedition. Fremont described the Washoe as being cautious of being close to them, but in time, when he showed no aggression, the Washoe came forward and gave him handfuls of pine nuts. Fremont described struggling through deep snow and being impressed by the Washoe’s skill with snowshoes. The Washoe willingly shared their knowledge of the land and eventually guided Fremont to a safe passage to California.

As more and more colonizers began infiltrating Washoe land, it was not long before relations grew hostile. The summer of 1844, just a few months after Fremont had passed through, a group of trappers left record of having shot and killed five Indians (either Washoe or Paiute) for having taken traps and perhaps horses. The Indians probably took those things in order to discourage the trappers from entering their land. After the deaths, the trappers searched the area, but not surprisingly found no more Indians. Most westward-migrating settlers had been conditioned by their experiences passing through the country of aggressively defensive tribes of the Great Plains and saw no distinction between different tribes. They expected the Washoe to be violent and dangerous and projected these characteristics upon them.

In 1846, the Washoe noticed the famed Donner party wagon train because they had never seen wagons before. They described seeing the wagons and wondering if they were a “monster snake”. In route to California, the Donner party reached the Sierras late in the year and got trapped in snow for a particularly harsh winter. The Washoe checked in with the stranded travelers a few times and brought them food when they could. Even so, in the face of suffering and starvation, the Donner Party resorted to cannibalism. When the Washoe witnessed them eating each other they were shocked and frightened. Although the Washoe faced hard times every winter and death by starvation sometimes occurred, they were never cannibalistic. Stories about the situation, some gruesome and some sympathetic, were told for many generations and were said to have added to the general mistrust of the white people.

In 1848, gold was “discovered” in California, and although until then, most of the Washoe had never seen white people, or had previously avoided them, this soon became impossible. The wagon trains came by the hundreds, and because most of the wagon trails had previously been Indian trails, encounters were numerous. Most of the new people were just passing through, but by 1849, several began to establish seasonal trading posts in Washoe territory.

By 1851, year-round trading posts were established, and colonizers became permanent residents on Washoe land. The settlers often chose to live on some of the most fertile gathering areas that the Washoe depended on. A few years after gold was found in California, silver was “discovered” in the Great Basin and the “Comstock Bonanza” lured many miners that had passed through back into Washoe territory.

The Euro-American perspective viewed land and its resources as objects of frontier opportunity and exploitation. In a short time, the colonizers had overused the pine nuts, seeds, game and fish that the Washoe had lived harmoniously with for thousands of years. By 1851, Indian Agent Jacob Holeman recommended that the government sign a treaty with the Washoe and wrote, “…the Indians having been driven from their lands, and their hunting ground destroyed without compensation, therefore – they are in many instances reduced to a state of suffering bordering on starvation.” All this happened in less than ten years after Fremont had passed through Washoe territory.

Settlers and miners cut down trees, including the sacred Piñon Pine to build buildings, support mine shafts, and even burn as fuel. The Piñon Pine woodlands that had once provided the Washoe, other tribes and all the animals with more than enough nuts became barren hillsides.

In 1859, Indian agent Frederick Dodge suggested removing the Washoe to two reservations, one at Pyramid Lake, and another at Walker Lake. Because the reservations were intended to be shared by the Washoe and the Paiute, it soon became apparent that this was impossible. Not only did the two tribes speak entirely different languages, but historically they had not always been friendly and trouble would no doubt arise if they were forced to live in close quarters. Furthermore, the Washoe intended to live on the land where the Maker had created them, and they resisted all attempts to be relocated. Numerous formal requests from Indian agents were made for a separate reservation for the Washoe, but the government ignored them all. By 1865, there were no stretches of unoccupied land large enough within traditional Washoe territory to form one reservation, so an agent made a recommendation that two separate 360-acre parcels be set aside for the Washoe.

The following year, in 1866, a new agent destroyed any hope of this happening when he sent a letter to his authorities that stated, “There is no suitable place for a reservation in the bounds of their territory, and, in view of their rapidly diminishing numbers and the diseases to which they are subjected, none is required.” This man wrongly believed that in time the Washoe would disappear. Between 1871 and 1877 several more requests for a reservation for the Washoe were made by agents, but again they were not heard. The government made no attempt to secure rights for the Washoe or to stop the destruction of the lands by the colonial culture. Settler’s livestock grazed the land intensely and grasses that had once provided the Washoe with seed were trampled and eaten. Commercial fishing was practiced on every stream and lake in the area and it was not long before the fish were depleted. At the height of the fishing, 70,000 pounds of fish were being sent from Lake Tahoe to Reno, Carson City, and Virginia City, Nevada. There were several attempts by the colonizers to stop the Washoe from fishing, but the Indians banded together and restrictions were relaxed. Even so, there were no longer enough fish for the Washoe to subsist on. Sagehens that used to “cover the hills like snow” were killed off by sport hunting as well.

Though the Washoe had tried their best to avoid the white settlers, their lands had been taken, their hunting grounds succumbed to farms, and the Pinyon groves were cut down. They soon found themselves dependent upon the settlers for jobs. Their new settlements were referred to at the time as “Indian colonies,” but were not formal Indian reservations.

Despite some local opposition, land was finally purchased for the Washoe in 1917. Two tracts of land were purchased near Carson City, Nevada that totaled 156.33 acres. This became the Carson Indian Community. Shortly after this purchase, the government received 40 acres of land south of Gardnerville from the Dressler family, to indefinitely be held in trust for the Washoe, now known as the Dresslerville Community. An additional 20 acres were acquired for the Washoe and Northern Paiute families who lived in Reno called the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony. Most of the lands purchased for the Washoe were rocky and had poor soil, but the people moved onto these areas and built the best homes that they could. Many were one-room shacks without electricity and running water. Eventually, the government built larger four-room houses.

Under the Indian Reorganization Act, between 1938 and 1940, the Washoe acquired 95 acres in the Carson Valley that became known as Washoe Ranch. Finally, the Washoe had agricultural land where they could raise animals and food. After settling on their newly returned land, the Washoe found it difficult to adapt to reservation life. They were traditionally a free-roaming people that were now restricted and confined to boundaries and were under constant monitoring by Indian Agents that pressured them to renounce their ancient customs in favor of colonial ways of living. The superintendent of the Reno Agency attacked several traditional practices, including the girl’s passage to womanhood. Ironically the practices that he targeted as “heathen” and “immoral” like giving gifts were similarly practiced at Euro-American birthdays and marriages. Another superintendent announced that traditional games that involved exchanging money were not permitted on government lands or Indian reservations, but he made no proclamations prohibiting similar games played by colonizers such as poker. Government officials went as far as to prohibit the use of traditional Washoe medicine.

The government had significantly reduced the area that the Washoe had designated as their ancestral homeland, and in 1951 the Washoe filed a claim to the Indian Claims Commission for their lands and resources that had been lost. The legal proceedings lasted nearly 20 years, and the Washoe finally received their claim in 1970. The final settlement was five million dollars, which “scarcely constitutes even a token compensation for the appropriation of an ancient territory and its resources which today comprise one of the richest and most attractive areas in the American West.

Also in 1970, a special act of Congress granted 80 acres in Alpine County, California to Washoe that had lived there for many years. This is now known as the Woodfords Community. In more recent years the tribe has been acquiring lands within their ancestral territory including, Frank Parcel, Lady’s Canyon, Babbit Peak, Uhalde Parcel, Wade Parcels, Olympic Valley, Incline Parcel, Upper and Lower Clear Creek Parcels. Some of the lands have been set aside as conservation and cultural lands for the Washoe People.

The federally recognized Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California now counts among its membership, some 2,000 people. With their deep roots for the Lake Tahoe area, they combine traditional and modern conservation practices in the protection and restoration of endangered habitats.

They are governed by a Tribal Council and a Chairman, consisting of 12 representatives from the Washoe Tribal Community Councils. The council is responsible for the cultural preservation of the Washoe history and culture and the Chairman is responsible for the daily operations of the tribe.

Contact Information:

Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California

800-76-WASHOE

Compiled & edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated October 2020.

Also See:

Lake Tahoe – Queen of the Sierra Nevadas

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Native American Photo Galleries

Sources:

United States Department of Agriculture-Forest Service

The Washoe People – Past and Present (USDA)