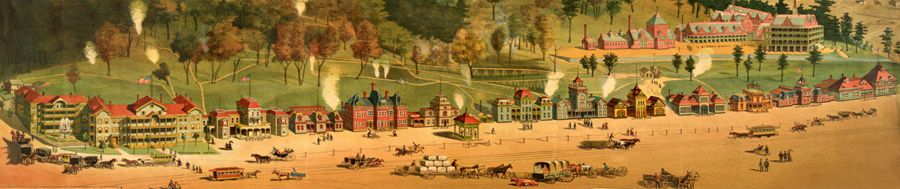

Hot Springs, Arkansas Bathhouses, 1888

Hot Springs, Arkansas, located along the Ouachita River in the Central Ouachita Mountains, is the county seat of Garland County and home to the Hot Springs National Park, the oldest federal reserve in the United States. The city is named for the natural thermal water that flows from 47 springs on the western slope of Hot Springs Mountain. These waters that flow out of the ground at 147 degrees have been popularly believed for centuries to possess medicinal properties and were a subject of legend among several Native American tribes.

Native Americans are thought to have occupied the area as early as the Paleo-Indian era in about 12,000 B.C. Archeological evidence shows that early Indians quarried stone in the area for various tools and spear points. Though these indigenous people more than likely took part in the soothing waters of the thermal hot springs, there is no documentation of this until 1771, when Jean-Bernard Bossu, a French navy captain and explorer, noted during a stay with the Quapaw Indians: “The Akanças country is visited very often by western Indians who come here to take baths,” for the hot waters “are highly esteemed by native physicians who claim that they are so strengthening.”

Other natives thought to have utilized the area were likely related to the historic Caddo Indians. Local legend speaks of the thermal springs as constituting a neutral ground in which various tribes, even at war, could co-exist in peace, at least temporarily.

The area was first explored In 1673 by Father Jacques Marquette and fur trader Louis Jolliet, who claimed the area for France. The 1763 Treaty of Paris ceded the land to Spain; however, in 1800, control was returned to France until the United States made the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Afterward, President Thomas Jefferson sent several expeditions to explore the new territory. One was the famous Louis & Clark Expedition, which explored the Pacific Northwest. Another was the Hunter-Dunbar Expedition, which explored “the hot springs” and the “Washita” River in present-day Arkansas and Louisiana. In December 1804, Dr. George Hunter and William Dunbar traveled up the Ouachita River, studying the hot springs for four weeks. Though they could not discover the springs’ water source, they found a lone log cabin and a few rudimentary shelters used by people already visiting the springs for their healing properties.

In 1807, a Lousiana planter Emmanuel Prudhomme became the first permanent settler of the village of Hot Springs, and others soon joined him. The site soon attracted regular visitors as people sought the reputed beneficial effects of the thermal springs.

The accommodations at Hot Springs were not praiseworthy in the early 1800s, as noted by one visitor:

“The accommodations for using the water are so entirely deficient that it would not be wonderful if but little was affected by them. The sweat house is rudely constructed with boards, which partially exclude the air, and a blanket stops the mouth of it. The patient has to come into the open air to dry himself, hurry on his clothes, and go home.”

On August 24, 1818, the Quapaw Indians ceded the land around the hot springs to the United States in a treaty. Arkansas became its own territory in 1819, and the following year, the Arkansas Territorial Legislature requested that the springs and adjoining mountains be set aside as a federal reservation. The same year, another treaty designated southwest Arkansas for Choctaw resettlement, amended in 1825 to redirect the Choctaw to Oklahoma.

Meanwhile, the first structure that could be considered a hotel opened in the new settlement of Hot Springs. In 1830, the first bathhouse was built by Asa Thompson, which was a primitive log structure with a wooden tub near a sweat bath. Two years later, a second log bathhouse with more tubs was built near the present-day Arlington Lawn and Superior Bathhouse.

By the early 1830s, the springs proved to be a significant attraction. In 1832, Congress reserved the area for federal use, exempting it from settlement and granting federal protection of the thermal waters. However, people found ways around that, and construction occurred near the springs anyway.

The first bathhouses were crude structures of canvas and lumber, little more than tents perched over individual springs or reservoirs carved out of the rock. Bathhouses made of wood frames could be found in Hot Springs by the 1850s. These replaced the crude huts and continued operating into the late 19th century. Wooden troughs carried water from the springs to a tank, and the bather could then manipulate the cold and hot water by pulling a rope. Afterward, the bather went to a special vapor room (a room over a thermal spring with cracks around two inches apart in the floor to allow vapor to rise). Following the vapor, the bather received a dousing of cold water before dressing.

When Hot Springs was incorporated in 1851, it was already home to two rows of hotels and several bathhouses and businesses. The city attracted not only seekers of leisure but also numerous invalids hoping to find relief in the mineral-laden springs.

During the Civil War, the Arkansas governor, fearing that Little Rock might be captured by Union troops in 1862, relocated the state records to Hot Springs. Hot Springs served as the state capital from May 6 to July 14 of that year. The Confederate government returned to Little Rock before relocating to Washington the following year. Afterward, Union troops advanced upon and captured Little Rock. Hot Springs was never occupied by Union troops and largely escaped the violence of the war save for two minor skirmishes that occurred on February 4, 1864.

When the war ended, settlement and construction occurred near the springs, with claimants using various legal means to establish property ownership. By 1870, the city of Hot Springs had a population of 1,200 inhabitants, and by 1873 six bathhouses and 24 hotels and boardinghouses stood near the springs. In 1875, the Rock Island narrow-gauge railroad arrived, bringing more growth and visitation to the city. Within no time, Samuel W. Fordyce and two other entrepreneurs financed the construction of the first luxury hotel in the area — the Arlington Hotel, which opened in 1875. At that time, it was the largest hotel in the state.

In the meantime, the fight over property rights continued into Congress and the Supreme Court. In 1877, Benjamin F. Kelley was appointed as the first superintendent of the reservation. He soon initiated several engineering projects, allowing private owners to convert the previously ramshackle downtown bathhouses into a row of attractive buildings. This decision and the railroad’s arrival transformed Hot Springs into a cosmopolitan spa that would attract visitors from across the nation.

In 1878, the federal government established a simple frame building over what was popularly known as the “mud hole” spring to service the poor, who could bathe there for free. Initially, the site was open to all, regardless of gender or race. However, a new brick building was erected in 1891 and later remodeled to address racial and gender segregation.

Hot Springs Creek, which ran right through the middle of all this activity, drained its own watershed and collected the runoff of the springs. Generally, it was an eyesore, dangerous at times of high water and mere collections of stagnant pools at dry times. In 1884 the federal government put the creek into a channel, roofed over it, and laid a sidewalk down above it. Much of it runs under Central Avenue and Bathhouse Row today.

In 1886, the Chicago White Stockings baseball franchise began spring training in Hot Springs. Afterward, more baseball teams followed, and by the early 20th century, Hot Springs was known for its baseball training camps. The city would continue to serve as a significant spring training site until the 1920s, when the franchises had moved to places with warmer climates in the winter, such as Florida and Arizona.

During the early 1900s, thousands of people flocked to the area to experience the water’s curative powers. Elaborate bathhouses were built to house many tourists visiting for springs and spa treatments. By this time, electric trolleys, telephone lines, and new stores across from Bathhouse Row tempted visitors.

Thoroughbred horse racing started in Hot Springs with the construction of Essex Park in 1904; however, a state law prohibiting betting on horse races was passed in 1907. In the following decades, the park was reopened and closed.

During the early 20th century, several institutions related to health continued to thrive. The Crystal Bathhouse opened in 1904 for use by African Americans, and the Levi Hospital was founded in 1914 and continues to operate today. However, the community also suffered several setbacks. A fire in 1905 killed as many as 25 people and destroyed nearly 400 buildings. Another in 1913 destroyed a significant portion of the city’s tourist district, including the Crystal Bathhouse.

In 1921, the government reservation was officially renamed Hot Springs National Park. Though it was officially the 18th unit in the new National Park Service system, some consider Hot Springs America’s first national park because of its designation as a reservation in 1832.

The Southern Club in Hot Springs, Arkansas, was often frequented by gangsters beginning in the 1920s. Today, the building serves as Josephine Tussaud’s Wax Museum. Photo by Detroit Publishing, 1900.

In 1926, Leo McLaughlin was elected mayor and fulfilled a campaign promise to run Hot Springs as an “open” town, which included legal gambling. As mayor, he reigned as the undisputed boss of Garland County politics for the next 20 years. During his time in office, many underworld characters frequented Hot Springs’ spas, and gambling became one of the town’s most popular forms of entertainment. The Southern Club became one of the favored hangouts for many of these gangsters, including Owen Vincent “Owney” Madden, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, and Al Capone.

Illegal gambling continued in Hot Springs after the McLaughlin political machine was ousted. By 1962, the city’s reputation had become so notorious that it became a significant issue in the gubernatorial race. The explosion of a bomb in the Vapors Casino in January 1963 made the problem of organized crime in the city a widespread concern. Soon after Winthrop Rockefeller took office as governor in 1967, he ordered the Arkansas State Police to crack down on gambling in the spa city.

Despite the closure of the city’s gambling establishments, as well as the shuttering of the downtown bathhouses from the 1960s to the 1980s, Hot Springs continued to grow. Today, it is called home to about 37,000 people.

Hot Springs National Park maintains Bathhouse Row, which preserves eight historic and architecturally significant bathhouse buildings and gardens along Central Avenue. These bathhouses, nicknamed “The American Spa,” were built between 1892 and 1923. These buildings, listed from south to north along the Row, include:

Lamar Bathhouse – This bathhouse opened on April 16, 1923, replacing a wooden Victorian structure named in honor of the former U. S. Supreme Court Justice Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar. The present structure cost $130,000 to build. The stone, brick, and stucco construction is moderately Spanish in flavor and coordinates well with the five other bathhouses with Spanish motifs. The Lamar was unique in offering a range of tub lengths for people of various heights. It also had a small coed gymnasium with another separate area for women. The most distinctive exterior component is the sun porch, with its windows of three sections and a wide center bay. The lobby, featuring a long counter of Tennessee marble, was the largest of the eight bathhouses on the Row. Murals and stenciling were added to the lobby and stairways sometime in the 1920s. In the mid-1940s, the interior halls and stairs were embellished with marble, ornamental iron balustrades, and silver glass interspersed with red panel wainscots. The Lamar Bathhouse closed on November 30, 1985. Today, the structure houses offices for park employees, the park archives, museum collection storage spaces, a small research library, and the park store, Bathhouse Row Emporium.

Buckstaff Bathhouse – Named for controlling shareholders George and Milo Buckstaff, this three-story building replaced the former Rammelsberg Bathhouse, a brick Victorian structure. The Neoclassical revival structure cost $125,000 to build and contains 27,000 square feet on three main floors. Because it has been in continuous operation since it opened on February 1, 1912, it is one of the best-preserved bathhouses. However, it has undergone many changes over the years. Originally it had a sizeable hydrotherapeutic department, which only it, the Fordyce, and the Imperial offered. Classical in design, with imposing Doric columns and urns gracing the front of the building, the Buckstaff features taupe brick with white stucco and wood trim. It epitomizes the Edwardian style of classically designed buildings famous during the first decade of the 20th century. Colorado marble is used throughout the interior, particularly in the bath halls. The floors are of white and colored hexagonal tile in varying patterns. All levels may be accessed through stairs or the building’s original elevator, with an ornate interior reminiscent of the Golden Age of Bathing. The current capacity of the building is 1,000 bathers per day.

Ozark Bathhouse – Completed in the summer of 1922, this two-story Spanish Colonial Revival style building cost $93,000. The bathhouse is set between low towers whose receding windows suggest the nascent Art Deco movement. The prominence of the towers was lessened during the 1942 renovation that brought the building’s wings forward in line with the front porch, which was enclosed at the same time. The plaster-cast window boxes are unique on Bathhouse Row. The cartouches on both sides of the front are of the scroll and shield type, with the center symbol described as The Tree of Health or The Tree of Life. Like the Quapaw, the Ozark was more impressive in its exterior facade than its interior appointments, with only 14,000 square feet and 27 tubs. It catered to a middle economic class of bathers unwilling to pay for frills. The Ozark closed in 1977. The painted wooden porch enclosure was removed in the late 1990s to return the building to its original appearance. Today, the Ozark houses the Hot Springs National Park Cultural Center, which features gallery spaces for displaying artwork from the park’s Artist-in-Residence Program and other temporary exhibitions. The building is operated by the park’s non-profit supporting organization, the Friends of Hot Springs National Park. Volunteers from the Friends group open the building for special occasions and on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday afternoons.

Quapaw Bathhouse – The longest building on Bathhouse Row occupies the site of two previous bathhouses, the Horseshoe and Magnesia. The Spanish colonial revival-style bathhouse opened in 1922. It was a moderately priced bathhouse that provided baths, vapors, showers, massages, and electrotherapy. The one-story, u-shaped floor plan featured a central dome covered with colored tile and topped with a copper cupola. The vaulted stained glass extends the lengths of the bath halls. It closed in 1968 and was reopened as Health Services, Inc. with only 20 tubs and services oriented towards hydrotherapy and physical therapy. It regained its original name a year before it was closed in 1984 following the discovery of significant damage to plaster ceilings and skylights. It then sat vacant until 2007, when work began to restore the building and ready it for new use. It was the first building to be leased and was reopened to the public in 2008. It is open from Wednesday to Monday, where visitors can partake in spa services again.

Fordyce Bathhouse – This three-story Spanish revival-style building opened on March 1, 1915. It cost over $212,000 to build, equip, and furnish and, when complete, encompassed approximately 28,000 square feet, making it the largest bathhouse on the Row. The first-floor lobby is filled with marble and stained glass transoms, a ceramic fountain at one end of the lobby, and a stained glass ceiling in the Men’s Bath Hall. The Dressing Rooms and Men’s Massage Rooms initially dominated the second floor. The third floor showcases the Music Room, with its patterned tile floor, stained glass ceiling, and Knabe grand piano. State Rooms speak of the luxury of relaxation, while the Gymnasium gives a glimpse of the forerunner of modern health clubs. The Fordyce was the only bathhouse to have a bowling alley. The Fordyce Spring was and still is on display in the basement. The Fordyce became the first bathhouse on the Row to go out of business when it suspended operations on June 30, 1962. Years later, it was extensively restored by 1989 and now serves as a museum and the park’s visitor center.

Maurice Bathhouse -This building replaced an existing Victorian-style building, the Independent Bathhouse, and opened for business on January 1, 1912. With a total floor space of 23,000 square feet, the three-story bathhouse had ample room for a complete range of services and amenities, including a gymnasium, staterooms, a roof garden, twin elevators, and in the 1930s, a therapeutic pool, situated in the basement. It was the only bathhouse on the Row to have a pool. Its square plan was designed in an eclectic combination of Renaissance Revival and Mediterranean styles commonly used by architects in California. The Maurice closed in November 1974.

Hale Bathhouse – Named for early bathhouse owner John Hale, the present Hale Bathhouse is at least the fourth building to use this name. The present Hale Bathhouse is the oldest visible structure on Bathhouse Row. Most of the present structure was completed in 1892. The two-and-one-half-story building was significantly enlarged and remodeled in 1914 in a classical revival style. The present building has 12,000 square feet on the two main floors. The lobby area was a sunroom where guests could relax in rocking chairs. In 1917, one of the hot springs was captured in a tiled enclosure in the basement, and this feature is still in place. In 1939, the building was redesigned again in the Mission Revival style, at which time, the brick was covered in stucco to look as it does today. The Hale closed on October 31, 1978.

Superior Bathhouse – This two-story brick building was constructed in “an eclectic commercial style of classical revival origin” and opened on February 1, 1916. The construction style was markedly different from that of its contemporaries’ Victorian bathhouses. The 11,000-square-foot building cost $68,000. The sun porch and the second-story portion of this bathhouse are topped with brick parapets. The smallest bathhouse in the Row, the Superior, also had the lowest rates and offered only basic hydrotherapy, mercury, and massage services. It closed in November 1983. Today, the Superior Bathhouse is home to the only brewery and distillery in a United States National Park and the only brewery worldwide to utilize thermal spring water to make their beer.

There is no entrance fee for the park.

Today, about 1,000,000 gallons of water flow from the springs daily. The flow rate is not affected by fluctuations in the rainfall in the area. Studies by National Park Service scientists have determined through radiocarbon dating that the water that reaches the surface in Hot Springs fell as rainfall 4,400 years ago. The water percolates very slowly down through the earth’s surface until it reaches superheated areas deep in the earth’s crust and then rushes rapidly to the surface to emerge from the 47 hot springs.

Hot Springs Creek flows from Whittington Avenue, then runs underground in a tunnel beneath Bathhouse Row on Central Avenue. It emerges from the tunnel south of Bathhouse Row and then flows through the southern part of the city before emptying into Lake Hamilton, a reservoir on the Ouachita River.

Aside from the Hot Springs National Park and Bathhouse Row, the city has numerous attractions, and several events are held throughout the year. The city also features multiple historic districts and numerous buildings on the National Historic Register of Historic Places.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2023.

Also See:

Gangsters, Thugs, and Mafia in Hot Springs

National Parks, Monuments & Historic Sites

Sources:

Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Hot Springs National Park

National Park Service

Wikipedia