Early American colonists came from various backgrounds, including Pilgrims, Separatists, and Puritans, who hoped to worship as they pleased. They were adventurers who charted coastlines and mapped inland trails. They were also profiteers with desires to turn new land into prosperity, wealth, and power.

The American colonies, also called thirteen colonies or colonial America, were established during the 17th and early 18th centuries in what is now a part of the eastern United States. The colonies grew geographically along the Atlantic coast and westward and numerically to 13 from their founding to the American Revolution (1775–81). Their settlements had spread far beyond the Appalachian Mountains and extended from Maine in the north to the Altamaha River in Georgia when the Revolution began. There were, at that time, about 2.5 million American colonists.

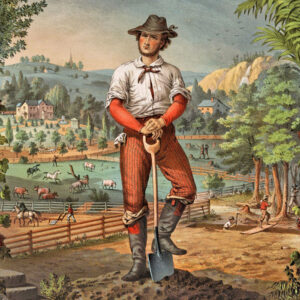

The English – The 13 colonies, except New York and Delaware, were English in leadership and origin. During the early days of all, save these two, the main, if not the sole, current of immigration was from England. The colonists came from every walk of life. They were men, women, and children of “all sorts and conditions.” Most were yeomen, small landowners, farm laborers, and artisans. With them were merchants and gentlemen who brought their stocks of goods or fortunes to the New World. Scholars came from Oxford and Cambridge to preach the gospel or teach. Now and then, the son of an English nobleman left his baronial hall behind and cast his lot with America. The people represented every religious faith — members of the Established Church of England; Puritans who had labored to reform that church; Separatists, Baptists, and Friends, who had left it altogether; and Catholics, who clung to the religion of their fathers.

New England was almost purely English. Between 1629 and 1640, the period of arbitrary Stuart government, about 20,000 Puritans emigrated to America, settling in the colonies of the far North. Although minor additions were made occasionally, the more significant portion of the New England people sprang from this original stock. Virginia also drew nearly all her immigrants from England alone for a long time. Not until the eve of the Revolution did other nationalities rival the English in numbers, mainly the Scotch-Irish and Germans. The populations of later English colonies — the Carolinas, New York, Pennsylvania, and Georgia — while receiving a steady stream of immigration from England, were constantly augmented by wanderers from the older settlements. New York was invaded by Puritans from New England in such numbers as to cause the Anglican clergymen there to lament that “free thinking spreads almost as fast as the Church.”

North Carolina was first settled toward the northern border by immigrants from Virginia. Some North

Carolinians, notably the Quakers, came from New England, tarrying in Virginia only long enough to learn how little they were wanted in that Anglican colony.

The Scotch-Irish – Next to the English in numbers and influence were the Scotch-Irish, Presbyterians in belief, and English in speech. Both religious and economic reasons sent them across the sea. Their Scotch ancestors, in the days of Cromwell, had settled in the north of Ireland when the conqueror’s sword had driven the native Irish. There the Scotch flourished for many years, enjoying their own form of religion in peace and growing prosperous in the manufacture of fine linen and woolen cloth. Then the blow fell. Toward the end of the 17th century, their religious worship was banned, and the English Parliament forbade the export of their cloth.

Within two decades, 20,000 Scotch-Irish left Ulster alone for America; during the 18th century, the migration continued to be heavy. Although no accurate record was kept, it is reckoned that the Scotch-Irish and the Scotch who came directly from Scotland composed one-sixth of the entire American population on the eve of the Revolution.

These newcomers in America made their homes chiefly in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. Coming late upon the scene, they found much of the land immediately upon the seaboard already taken up. For this reason, most of them became frontier people settling in the interior and upland regions. There they cleared the land, laid out their small farms, and worked as ” sturdy yeomen on the soil,” hardy, industrious, and independent in spirit, sharing neither the luxuries of the wealthy planters nor the easy life of the leisurely merchants. They added woolen and linen manufacturers to their agriculture, which, flourishing in the supple fingers of their tireless women, made heavy inroads upon the trade of the English merchants in the colonies.

The Germans – Third among the colonists in order of numerical importance were the Germans. From the very beginning, they appeared in colonial records. A number of the artisans and carpenters in the first Jamestown colony were of German descent. Peter Minuit, the famous governor of New Netherland, was a German from Wesel on the Rhine, and Jacob Leisler, leader of a popular uprising against the provincial administration of New York, was a German from Frankfort-on-Main. The wholesale migration of Germans began with the founding of Pennsylvania. Penn diligently searched for thrifty farmers to cultivate his lands, and he made a special effort to attract peasants from the Rhine country. A significant association, known as the Frankfort Company, bought more than 20,000 acres from him and, in 1684, established a center at Germantown for the distribution of German immigrants. In old New York, Rhinebeck-on-the-Hudson became a similar center for distribution. From Maine to Georgia, inducements were offered to the German farmers, and in nearly every colony were to be found, in time, German settlements. The migration became so large that German princes were frightened at losing many subjects, and England was alarmed by the influx of foreigners into her overseas dominions. Yet nothing could stop the movement. By the end of the colonial period, the number of Germans had risen to more than 200,000.

The majority of them were Protestants from the Rhine region and South Germany. Wars, religious controversies, oppression, and poverty drove them to America. Though most of them were farmers, there were also among them skilled artisans who contributed to the rapid growth of industries in Pennsylvania. Their iron, glass, paper, and woolen mills, dotted here and there among the thickly settled regions, added to the wealth and independence of the province.

Unlike the Scotch-Irish, the Germans did not speak the language of the original colonists or mingle freely with them. They kept to themselves, built schools, founded newspapers, and published books. Their clannish habits often irritated their neighbors and led to occasional agitations against ” foreigners.” However, no severe collisions seem to have occurred. In the days of the Revolution, German soldiers from Pennsylvania fought in the patriot armies side by side with soldiers from the English and Scotch-Irish sections.

Other Nationalities – Though the English, the Scotch-Irish, and the Germans made up the bulk of the colonial population, there were other racial strains, varying in numerical importance but contributing their share to colonial life. From France came the Huguenots fleeing from the king’s decree, which inflicted terrible penalties upon Protestants.

From “Old Ireland ” came thousands of native Irish, Celtic in race and Catholic in religion. Like their northern Scotch-Irish neighbors, they revered neither the government nor the Church of England imposed upon them by the sword. How many came, we do not know, but shipping records of the colonial period show that boatload after boatload left the southern and eastern shores of Ireland for the New World. Undoubtedly thousands of their passengers were Irish of the native stock.

The constant appearance of Celtic names in the records of various colonies well sustains this surmise. The Jews, then as ever engaged in their age-long battle for religious and economic toleration, found in the American colonies not complete liberty but certainly more freedom than they enjoyed in England, France, Spain, or Portugal. The English law did not recognize their right to live in any of the dominions, but owing to the easy-going habits of the Americans, they were allowed to filter into the seaboard towns. The treatment they received there varied. On one occasion, the mayor and council of New York forbade them to sell by retail, and on another, prohibited the exercise of their religious worship. Newport, Philadelphia, and Charleston were more hospitable, and there, large Jewish colonies, consisting principally of merchants and their families, flourished despite nominal prohibitions of the law.

Though the small Swedish colony in Delaware was quickly submerged beneath the tide of English migration, the Dutch in New York continued to hold their own for more than 100 years after the English conquest in 1664. At the end of the colonial period, over one-half of the 170,000 inhabitants of the province were descendants of the original Dutch — still distinct enough to give a decided cast to the life and manners of New York. Many of them clung as tenaciously to their mother tongue as they did to their spacious farmhouses or Dutch ovens, but they were slowly losing their identity as the English pressed in beside them to farm and trade.

The melting pot had begun its historic mission.

The Process of Colonization

From one side, colonization, whatever the motives of the emigrants, was an economic matter. It involved using capital to pay for their passage, sustain them on the voyage, and start them on the way to production. Under this stern economic necessity, Puritans, Scotch-Irish, Germans, and all were alike laid.

Immigrants Who Paid Their Own Way – Many immigrants to America in colonial days were capitalists, in a small or significant way, and paid their own passage. What proportion of the colonists could finance their voyage across the sea is a matter of pure conjecture. Undoubtedly, a considerable number could do so, for we can trace the family fortunes of many early settlers. Henry Cabot Lodge, an authority for the statement that ” the settlers of New England were drawn from the country gentlemen, small farmers, and yeomanry of the mother country… Many of the emigrants were men of wealth, as the old lists show, and all of them, with few exceptions, were men of property and good standing. They did not belong to the classes from which emigration is usually supplied, for they all had a stake in the country they left behind.” Though it would be interesting to know how accurate this statement is or how applicable to the other colonies, no study has been made to gratify that interest. For now, it is an unsolved problem just how many colonists could bear the cost of their own transfer to the New World.

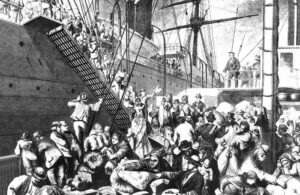

Indentured Servants – That at least tens of thousands of immigrants could not pay for their passage is established beyond the shadow of a doubt by the shipping records that have come down to us. The sea voyage cost was a great barrier for the poor who wanted to go to America. To overcome this difficulty, ship owners and other persons of means furnished the passage money to immigrants in return for their promise, or bond, to work for a term of years to repay the sum advanced. This system was called indentured servitude.

The number of bondservants probably exceeded the original 20,000 Puritans, the yeomen, the Virginia gentlemen, and the Huguenots combined. Down the coast from Massachusetts to Georgia, were to be found in the fields, kitchens, and workshops, men, women, and children serving out terms of bondage generally ranging from five to seven years. In the proprietary colonies, the proportion of bondservants was very high. The Baltimores, Penns, Carterets, and other promoters anxiously sought workers of every nationality to till their fields, for land without labor was worth no more than land on the moon. Hence the gates of the proprietary colonies were flung wide open. Every inducement was offered to immigrants through cheap land, and special efforts were made to increase the population by importing servants. In Pennsylvania, it was not uncommon to find a master with 50 bond servants on his estate. It has been estimated that two-thirds of all the immigrants into Pennsylvania between the opening of the eighteenth century and the outbreak of the Revolution were in bondage. In the other Middle colonies, the number was doubtless not so large; but it formed a considerable part of the population.

The story of this traffic in white servants is one of the most striking things in labor history. Bondmen differed from the serfs of the feudal age in that they were not bound to the soil but to the master. They likewise differed from the negro slaves in that their servitude had a time limit. Still, they were subject to many special disabilities. It was, for instance, a common practice to impose on them penalties far heavier than were imposed upon freemen for the same offense.

A free citizen of Pennsylvania who indulged in horse racing and gambling was let off with a fine; a white servant guilty of the same unlawful conduct was whipped at the post and fined as well. The ordinary life of the white servant was also severely restricted. A bondman could not marry without his master’s consent, engage in trade, or refuse work assigned to him. For an attempt to escape or, indeed, for any infraction of the law, the term of service was extended. According to Lodge, the condition of white bondmen in Virginia” was little better than that of slaves. Loose indentures and harsh laws put them at the mercy of their masters.” It would not be unfair to add that such was their lot in all other colonies. Their fate depended upon the temper of their masters.

Cruel as was the system in many ways, it gave thousands of people in the Old World a chance to reach the New — an opportunity to wrestle with fate for freedom and a home of their own. When their weary years of servitude were over, they might obtain land or settle as free mechanics in the towns if they survived. For many a bondman, the gamble proved to be a losing venture because he could not rise out of the state of poverty and dependence into which his servitude carried him. For thousands, on the contrary, bondage proved to be a real avenue to freedom and prosperity. Some of the best citizens of America have the blood of indentured servants in their veins.

The Transported – Involuntary Servitude – In their anxiety to secure settlers, the companies and proprietors having colonies in America either resorted to or connived at the practice of kidnapping men, women, and children from the streets of English cities. In 1680 it was officially estimated that ” 10,000 people were spirited away ” to America. Many of the victims of the practice were young children, for the traffic in them was highly profitable. Orphans and dependents were sometimes disposed of in America by relatives unwilling to support them. In a single year, 1627, about 1,500 children were shipped to Virginia.

In this gruesome business, there lurked many tragedies and very few romances. Parents were separated from their children and husbands from their wives. Hundreds of skilled artisans — carpenters, smiths, and weavers — utterly disappeared as if swallowed up by death. Thus, a few were dragged off to the New World to be sold into servitude for five or seven years, later became prosperous, and returned home with fortunes. In one case, a young man forcibly carried over the sea lived to make his way back to England and establish his claim to a peerage.

Akin to the kidnapped, at least in economic position, were convicts deported to the colonies for life instead of fines and imprisonment. The Americans protested vigorously but ineffectually against this practice. Indeed, they exaggerated its evils, for many “criminals” were only mild offenders against unduly harsh and cruel laws. A peasant caught shooting a rabbit on a lord’s estate or a luckless servant girl who purloined a pocket handkerchief was branded as a criminal along with sturdy thieves and incorrigible rascals. Other transported offenders were “political criminals”; that is, persons who criticized or opposed the government. This class included now Irish who revolted against British rule in Ireland; now Cavaliers who championed the king against the Puritan revolutionists; Puritans, in turn, dispatched after the monarchy was restored; and Scotch and English subjects in general who joined in political uprisings against the king.

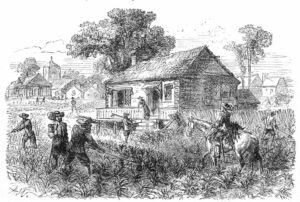

African Slaves – Rivaling in numbers, over time, the indentured servants and whites carried to America against their will were the African Americans brought to America and sold into slavery. When this form of bondage was first introduced into Virginia in 1619, it was considered a temporary necessity to be discarded with the increase of the white population. Moreover, it does not appear that those planters who first bought negroes at the auction block intended to establish a system of permanent bondage. Only by a slow process did chattel slavery take firm root and become recognized as the leading source of the labor supply. In 1650, thirty years after the introduction of slavery, there were only 300 Africans in Virginia.

The tremendous increase in later years was due in no small measure to the excessive zeal for profits that seized slave traders both in Old and New England. Finding it relatively easy to secure negroes in Africa, they crowded the Southern ports with their vessels. The English Royal African Company sent to America annually between 1713 and 1743 from 5,000 to 10,000 slaves. The ship owners of New England were not far behind their English brethren in pushing this extraordinary traffic.

As the proportion of the negroes to the free white population steadily rose, and as whole sections were overrun with slaves and slave traders, the Southern colonies grew alarmed. In 1710, Virginia sought to curtail the importation by placing a duty of £5 on each slave. This effort was futile, for the royal governor promptly vetoed it. From time to time, similar bills were passed, only to meet with royal disapproval. South Carolina, in 1760, absolutely prohibited the importation, but the British crown killed the measure. As late as 1772, Virginia, not daunted by a century of rebuffs, sent to George III a petition in this vein: “The importation of slaves into the colonies from the coast of Africa hath long been considered as a trade of great inhumanity, and under its present encouragement, we have too much reason to fear, will endanger the very existence of Your Majesty’s American dominions… Deeply impressed with these sentiments, we most humbly beseech Your Majesty to remove all those restraints on Your Majesty’s governors of this colony which inhibit their assenting to such laws as might check so very pernicious a commerce.”

All such protests were without avail. The black population grew by leaps and bounds until it amounted to more than half a million on the eve of the Revolution. In five states — Maryland, Virginia, the two Carolinas, and Georgia — the slaves nearly equaled or exceeded the whites in number. In South Carolina, they formed almost two-thirds of the population. Even in the Middle colonies of Delaware and Pennsylvania, about one-fifth of the inhabitants were from Africa.

To the North, the proportion of slaves steadily diminished, although chattel servitude was on the same legal footing as in the South. In New York, approximately one in six, and New England, one in 50 were African American, including a few freedmen. The climate, the soil, the commerce, and the industry of the North were all unfavorable to the growth of a servile population. Still, slavery, though sectional, was a part of the national system of economy. Northern ships carried slaves to the Southern colonies and the produce of the plantations to Europe. “If the Northern states will consult their interest, then we will not oppose the increase in slaves which will increase the commodities of which they will become the carriers,” said John Rutledge, of South Carolina, in the convention, which framed the Constitution of the United States. “What enriches a part enriches the whole, and the states are the best judges of their particular interest,” responded Oliver Ellsworth, the distinguished spokesman of Connecticut.

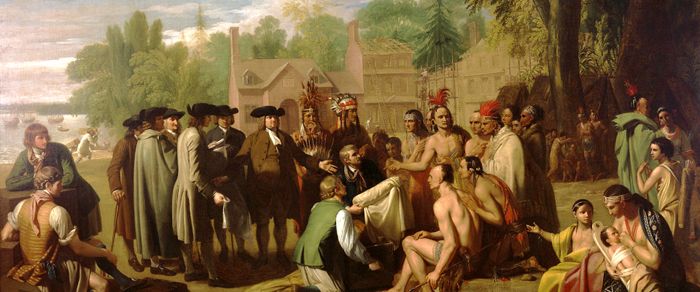

Relations with the Indians and the French Indian Affairs – It is difficult to make general statements about the colonists’ relations with the Indians. The problem was presented in different shapes in different sections of America. It was not handled according to any coherent or uniform plan by the British government, which alone could speak for all the provinces simultaneously. Neither did the proprietors and the governors who succeeded one another in an irregular train have the consistent policy or the matured experience necessary for dealing wisely with Indian matters. As the difficulties arose mainly on the frontiers, where the restless and pushing pioneers made their way with guns and axes, nearly everything that happened resulted from chance rather than calculation. A personal quarrel between traders and an Indian, a jug of whisky, a keg of gunpowder, the exchange of guns for furs, personal betrayal, or a flash of bad temper often set in motion destructive forces of the most terrible character.

On one side of the ledger, innumerable generous records may be set — of Squanto and Samoset teaching the Pilgrims the ways of the wilds, of Roger Williams buying his lands from the friendly natives, or of William Penn treating with them on his arrival in America. On the other side of the ledger must be recorded many a cruel and bloody conflict as the frontier rolled westward with deadly precision. Sensing their doom, the Pequot on the Connecticut border fell upon the tiny settlements with awful fury in 1637, only to face equally terrible punishment. A generation later, King Philip, son of Massasoit, the friend of the Pilgrims, called his tribesmen to a war of extermination, which brought the strength of all of New England to the field and ended in his destruction. In New York, the relations with the Indians, especially with the Algonquin and the Mohawk, were marked by periodic and desperate wars.

Virginia and her Southern neighbors suffered, as did New England. In 1622 Opecacano, a brother of Powhatan and a friend of the Jamestown settlers launched a general massacre; and in 1644, he attempted a war of extermination. In 1675 the whole frontier was ablaze. Nathaniel Bacon vainly tried to stir the colonial governor to put up an adequate defense and, failing in that plea, himself headed a revolt and a successful expedition against the Indians. As the Virginia outposts advanced into the Kentucky country, the strife with the natives was transferred to that “dark and bloody ground” while to the southeast, a desperate struggle with the Tuscaroras called forth the combined forces of the two Carolinas and Virginia.

New Jersey and Delaware were saved from such horrors because of their geographical location. Pennsylvania, consistently following a policy of conciliation, was likewise spared until her western vanguard came into total conflict with the allied French and Indians. By clever negotiations and treaties of alliance, Georgia managed to keep on fair terms with her belligerent Cherokee and Creek. But neither diplomacy nor generosity could stay the inevitable conflict as the frontier advanced, especially after the French soldiers enlisted the Indians in their imperial enterprises. It was then that desultory fighting became general warfare.

By Charles Austin Beard and Mary Ritter Beard; History of the United States, Macmillan, 1921.