“How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?” Samuel Johnson, the great English writer and dictionary-maker, posed this question in 1775. He was among the first, but certainly not the last, to contrast the noble aims of the American Revolution with the presence of 450,000 enslaved African Americans in the 13 colonies.

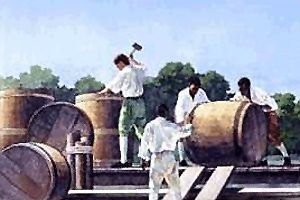

Slavery was practiced in every colony in 1775, but it was crucial to the economy and social structure of the Chesapeake region south to Georgia. Slave labor produced the great export crops of the South — tobacco, rice, indigo, and naval stores. Bringing slaves from Africa and the West Indies made the settlement of the New World possible and highly profitable. Who could predict what breaking away from the British Empire might mean for black people in America?

The British governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, quickly saw the vulnerability of the South’s slaveholders. In November 1775, he issued a proclamation promising freedom to any slave of a rebel who could make it to the British lines. Dunmore organized an “Ethiopian” brigade of about 300 African Americans, who saw action at the Battle of Great Bridge on December 9, 1775. Dunmore and the British were soon expelled from Virginia, but the prospect of armed former slaves fighting alongside the British must have struck fear into plantation masters across the South.

African Americans in New England rallied to the patriot cause and were part of the militia forces organized into the new Continental Army. Approximately five percent of the American soldiers at the Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775) were black. New England blacks mainly served in integrated units and received the same pay as whites, although no African American is known to have held a rank higher than corporal.

It has been estimated that 5,000 black soldiers fought on the patriot side during the Revolutionary War. The exact number will never be known because 18th-century muster rolls usually did not indicate race. Careful comparisons between muster rolls and church, census, and other records have recently helped identify many black soldiers. Additionally, various eyewitness accounts indicate the level of African Americans’ participation during the war. Baron von Closen, a member of Rochambeau’s French army at Yorktown, wrote in July 1781, “A quarter of them [the American army] are Negroes, merry, confident and sturdy.”

The use of African Americans as soldiers, whether freemen or slaves, was avoided by Congress and General George Washington early in the war. The prospect of armed slave revolts proved more threatening to white society than British redcoats. General Washington allowed the enlistment of free blacks with “prior military experience” in January 1776. It extended the enlistment terms to all free blacks in January 1777 to help fill the depleted ranks of the Continental Army. Because the states constantly failed to meet their quotas of manpower for the army, Congress authorized the enlistment of all blacks, free and slave, later in 1777. Of the southern colonies, only Maryland permitted African Americans to enlist. In 1779, Congress offered slave masters in South Carolina and Georgia $1,000 for each slave they provided to the army, but the legislatures of both states refused the offer. Thus, the most significant number of African American soldiers in the American army came from the North.

In July 1778, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, the first all-black military unit in America, was assembled into service under the command of white officers.

Although most Continental regiments were integrated, the elite First Rhode Island was a notable exception. Mustered into service in July 1778, the First Rhode Island numbered 197 black enlisted men commanded by white officers. Baron von Closen described the regiment as “the most neatly dressed, the best under arms, and the most precise in its maneuvers.” The regiment received its baptism of fire at the Battle of Rhode Island (Newport) on August 29, 1778, successfully defeating three assaults by veteran Hessian troops. At the siege of Yorktown on the night of October 14, 1781, the regiment’s light company participated in the assault and capture of Redoubt 10. On June 13, 1783, the regiment was disbanded, receiving high praise for its service. Another notable black unit, recruited in the French colony of St. Domingue (present-day Haiti), fought with the French and patriots at the Battle of Savannah on October 9, 1779.

When the British launched their southern campaign in 1780, one of their aims was to scare Americans back to the crown by raising the fear of massive slave revolts. The British encouraged slaves to flee to their strongholds, promising ultimate freedom. The strategy backfired, as slave owners rallied to the patriot cause as the best way to maintain order and the plantation system. Tens of thousands of African Americans sought refuge with the British, but fewer than 1,000 served as soldiers. The British heavily used escapees as teamsters, cooks, nurses, and laborers. At the war’s conclusion, some 20,000 blacks left with the British, preferring an uncertain future elsewhere to a return to their old masters. American blacks ended up in Canada, Britain, the West Indies, and Europe. Some were sold back into slavery. In 1792, 1,200 black loyalists who had settled in Nova Scotia left for Sierra Leone, a colony on the west coast of Africa established by Britain specifically for former slaves.

The Revolution brought change for some American blacks, although nothing approached full equality. The courageous military service of African Americans and the revolutionary spirit ended slavery in New England almost immediately. The middle states of New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey adopted policies of gradual emancipation from 1780 to 1804. Many founders opposed slavery in principle (including some whose wealth was primarily in human property). The voluntary freeing of slaves increased following the Revolution. Still, free blacks in the North and South faced persistent discrimination in virtually every aspect of life, notably employment, housing, and education. Many founders hoped that slavery would eventually disappear in the American South. When cotton became king in the South after 1800, this hope died. There was just too much profit to be made working slaves on cotton plantations. However, the statement of human equality in the Declaration of Independence was never entirely forgotten. It remained an idea that civil rights activists could appeal to through the following decades.

In the Massachusetts State Archives is a petition to the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, stating that in the “late Battle at Charlestown,” a man from Colonel Frye’s Regiment “behaved like an experienced officer” and that in this man “centers a brave and gallant soldier.” This document, dated in December 1775, just six months after the Battle of Bunker Hill, is signed by 14 officers present at the battle, including Colonel William Prescott. Of the 2,400 to 4,000 colonists who participated in the battle, no other man is singled out in this manner.

This hero of the Battle of Bunker Hill is Salem Poor of Andover, Massachusetts. Although documents show that Poor, along with his regiment and two others, were sent to Bunker Hill to build a fort and other fortifications on the night of June 16, 1775, we have no details about just what Poor did to earn the praise of these officers. The petition states, “to set forth the particulars of his conduct would be tedious.” Perhaps his heroic deeds were too many to mention.

Few details of this hero’s life are available to us. Born a slave in the late 1740s, Poor managed to buy his freedom in 1769 for 27 pounds, representing a year’s salary for the typical working man. He married Nancy, a free African-American woman, and they had a son. Salem Poor left his wife and child behind in May 1775 and fought for the patriot cause at Bunker Hill, Saratoga, and Monmouth. We can only speculate about the motives for Poor’s sacrifice: was it patriotism, a search for new experience, or the prospect of a new and better life? The Battle of Bunker Hill was a daring and provocative act against established authority; all who participated could have been hanged for treason. Shut out from many opportunities in colonial society, Salem Poor chose to fight for an independent nation. In the words of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the bravery of Poor and other African-American soldiers “has a peculiar beauty and merit.”

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

African American History in the United States

American Indians and the American Revolution

Causes of the American Revolution

Privateers in the American Revolution

Source: National Park Service