By Pat Garrett

During the weeks following the Kid’s escape, I was censured by some for my seeming unconcern and inactivity in the matter of his re-arrest. I was egotistical enough to think I knew my own business best and preferred to accomplish this duty, if possible at all, in my own way. I was constantly, but quietly, at work, seeking sure information and maturing my plans of action. I did not lay about the Kid’s old haunts nor disclose my intentions and operations to anyone. I stayed at home, most of the time, and busied myself about the ranch. If my seeming unconcern deceived the people and gave the Kid confidence in his security, my end was accomplished. It was my belief that the Kid was still in the country and haunted the vicinity of Fort Sumner, yet there was some doubt mingled with my belief. He was never taken for a fool but was credited with the possession of extraordinary forethought and cool judgment for one of his age. It seemed incredible that, in his situation, with the extreme penalty of law, the reward of detection, and the way of successful flight and safety open to him — with no known tie to bind him to that dangerous locality — it seemed incredible that he should linger in the Territory. My first task was to solve my doubts.

Early in July, I received a reply from a letter I had written to Mr. Brazel. I was at Lincoln when this letter came to me. Mr. Brazel was dodging and hiding from the Kid.

He feared his vengeance on account of the part which he, Brazel, had taken in his capture. Many others “trembled in their boots” at the knowledge of his escape, but most of them talked him out of his resentment or conciliated him in some manner.

Brazel’s letter gave me no positive information. He said he had not seen the Kid since his escape but, from many indications, believed he was still in the country. He offered me any assistance in his power to recapture him. I again wrote to Brazel, requesting him to meet me at the mouth of Tayban Arroyo an hour after dark on the night of the 13th day of July.

A gentleman named John W. Poe, who had superseded Frank Stewart, in the employ of the stockmen of the Canadian, was at Lincoln on business, as was one of my deputies, Thomas K. McKinney. I first went to McKinney and told him I wanted him to accompany me on a business trip to Arizona, that we would go down home and start from there. He consented. I then went to Poe, and to him, I disclosed my business and all its particulars, showing him my correspondence. He also complied with my request that he should accompany me.

We three went to Roswell and started up the Rio Pecos from there on the night of July 10. We rode mostly in the night, followed no roads, but taking unfrequented routes, and arrived at the mouth of Tayban Arroyo, five miles south of Fort Sumner one hour after dark on the night of July 13. Brazel was not there. We waited nearly two hours, but he did not come. We rode off a mile or two, staked our horses, and slept until daylight. Early in the morning, we rode up into the hills and prospected awhile with our field glasses.

Poe was a stranger in the county, and there was little danger that he would meet anyone who knew him at Fort Sumner. So, after an hour or two spent in the hills, he went into Fort Sumner to take observations. I advised him, also, to go on to Sunnyside, seven miles above Fort Sumner, and interview M. Rudolph, Esq., in whose judgment and discretion I had great confidence. I arranged with Poe to meet us that night at moonrise, at La Punta de la Glorieta, four miles north of Fort Sumner. Poe went on to the plaza, and McKinney and I rode down into the Pecos Valley, where we remained during the day. At night we started out circling the town and met Poe exactly on time at the trysting place.

Poe’s appearance at Fort Sumner had excited no particular observation, and he had gleaned no news there. Rudolph thought, from all indications, that the Kid was about, and yet, at times, he doubted. His cause for doubt seemed to be based on no evidence except the fact that the Kid was no fool, and no man in his senses, under the circumstances, would brave such danger.

I then concluded to go and have a talk with Peter Maxwell, Esq., in whom I felt sure I could rely. We had ridden to within a short distance of Maxwell’s grounds when we found a man in camp and stopped. To Poe’s great surprise, he recognized in the camper an old friend and former partner in Texas, named Jacobs.

We unsaddled here, got some coffee, and, on foot, entered an orchard which runs from this point down to a row of old buildings, some of them occupied by Mexicans, not more than sixty yards from Maxwell’s house.

We approached these houses cautiously, and when within earshot, heard the sound of voices conversing in Spanish. We concealed ourselves quickly and listened, but the distance was too great to hear words or even distinguish voices. Soon a man arose from the ground, in full view but too far away to recognize. He wore a broad-brimmed hat, a dark vest, and pants and was in his shin sleeves. With a few words, which fell like a murmur on our ears, he went to the fence, jumped it, and walked down towards Maxwell’s house.

Little as we then suspected it, this man was the Kid. We learned, subsequently, that, when he left his companions that night, he went to the house of a Mexican friend, pulled off his hat and boots, threw himself on a bed, and commenced reading a newspaper.

He soon, however, hailed his friend, who was sleeping in the room, told him to get up and make some coffee, adding: — “Give me a butcher knife, and I will go over to Pete’s and get some beef; I’m hungry.” The Mexican arose, handed him the knife, and the Kid, hatless and in his stocking feet, started to Maxwell’s, which was but a few steps distant.

When the Kid, by me unrecognized, left the orchard, I motioned to my companions, and we cautiously retreated a short distance and, to avoid the persons whom we had heard at the houses, took another route, approaching Maxwell’s house from the opposite direction. When we reached the porch in front of the building, I left Poe and McKinney at the end of the porch, about twenty feet from the door of Pete’s room, and went in. It was near midnight, and Pete was in bed. I walked to the head of the bed and sat down on it, beside him, near the pillow. I asked him as to the whereabouts of the Kid. He said that the Kid had certainly been about, but he did not know whether he had left or not. At that moment, a man sprang quickly into the door, looking back, and called twice in Spanish, “Who conies there?” No one replied, and he came on in. He was bareheaded. From his step, I could perceive he was either barefooted or in his stocking- feet and held a revolver in his right hand and a butcher knife in his left.

He came directly towards me. Before he reached the bed, I whispered: “Who is it, Pete?” but received no reply for a moment. It struck me that it might be Pete’s brother-in-law, Manuel Abreu, who had seen Poe and McKinney and wanted to know their business. The intruder came close to me, leaned both hands on the bed, his right hand almost touching my knee, and asked, in a low tone: — “Who are they, Pete?” — at the same instant, Maxwell whispered to me. “That’s him!” Simultaneously the Kid must have seen, or felt, the presence of a third person at the head of the bed. He raised quickly his pistol, a self cocker, within a foot of my breast. Retreating rapidly across the room, he cried: “Quien es? Quien es?” (“Who’s that? Who’s that?”) All this occurred in a moment. Quickly as possible, I drew my revolver and fired, threw my body aside, and fired again. The second shot was useless; the Kid fell dead. He never spoke. A struggle or two, a little strangling sound as he gasped for breath, and the Kid was with his many victims.

Maxwell had plunged over the foot of the bed on the floor, dragging the bedclothes with him. I went to the door and met Poe and McKinney there. Maxwell rushed past me, out on the porch; they threw their guns down on him when he cried: “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot.” I told my companions I had got the Kid. They asked me if I had not shot the wrong man. I told them I had made no blunder that I knew the Kid’s voice too well to be mistaken. The Kid was entirely unknown to either of them. They had seen him pass in, and, as he stepped on the porch, McKinney, who was sitting, rose to his feet; one of his spurs caught under the boards and nearly threw him.

The Kid laughed but probably, saw their guns as he drew his revolver and sprang into the doorway, as he hailed: “Who comes there?” Seeing a bareheaded, barefooted man, in his shirt-sleeves, with a butcher knife in his hand, and hearing his hail in excellent Spanish, they naturally supposed him to be a Mexican and an attaché of the establishment, hence their suspicion that I had shot the wrong man.

We now entered the room and examined the body. The ball struck him just above the heart and must have cut through the ventricles. Poe asked me how many shots I fired; I told him two, but I had no idea where the second one went. Both Poe and McKinney said the Kid must have fired then, as there were surely three shots fired. I told them that he had fired one shot between my two. Maxwell said that the Kid fired; yet, when we came to look for bullet marks, none from his pistol could be found.

We searched long and faithfully — found both my bullet marks and none other; so, against the impression and senses of four men, we had to conclude that the Kid did not fire at all. We examined his pistol — a self-cocker, caliber 41. It had five cartridges and one shell in the chambers, the hammer resting on the shell, but this proves nothing, as many carry their revolvers in this way for safety; besides, this shell looked as though it had been shot sometime before.

It will never be known whether the Kid recognized me or not. If he did, it was the first time, during all his life of peril, that he ever lost his presence of mind or failed to shoot first and hesitate afterward. He knew that a meeting with me meant surrender or fight. He told several persons about Sumner that he bore no animosity against me and had no desire to injure me. He also said that he knew, should we meet, he would have to surrender, kill me, or get killed himself. So, he declared his intention, should we meet, to commence shooting on sight.

On the following morning, the alcalde, Alejandro Segura, held an inquest on the body. Hon. M. Rudolph, of Sunnyside, was foreman of the coroner’s jury. They found a verdict that William H. Bonney came to his death from a gun-shot wound, the weapon in the hands of Pat F. Garrett, that the fatal wound was inflicted by the said Garrett in the discharge of his official duty sheriff, and that the homicide was justifiable.

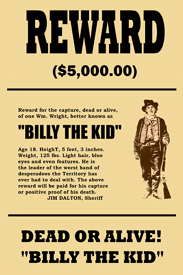

The body was neatly and properly dressed and buried in the military cemetery at Fort Sumner, July 15, 1881. On the day of his death, his exact age was 21 years, seven months, and 21 days.

I said that the body was buried in the cemetery at Fort Sumner; I wish to add that it is there today intact. Skull, fingers, toes, bones, and every hair of the head that was buried with the body on that 15th day of July, doctors, newspaper editors, and paragraphers to the contrary notwithstanding. Some presuming swindlers have claimed to have the Kid’s skull on exhibition, or one of his fingers, or some other portion of his body, and one medical gentleman has persuaded credulous idiots that he has all the bones strung upon wires. It is possible that there is a skeleton on exhibition somewhere in the States, or even in this Territory, which was procured somewhere down the Rio Pecos. We have them, lots of them in this section. The banks of the Pecos are dotted from Fort Sumner to the Rio Grande with unmarked graves, and the skeletons are of all sizes, ages, and complexions. Any showman of ghastly curiosities can resurrect one or all of them, and place them on exhibition as the remains of Dick Turpin, Jack Shepherd, Cartouche, or the Kid, with no one to say him nay; so they don’t ask the people of the Rio Pecos to believe it.

Again I say that the Kid’s body lies undisturbed in the grave — and I speak of what I know.

By Pat Garrett, 1882. Compiled by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Author & Notes: This article excerpted from Pat Garrett’s book, The Authentic Life of Billy, The Kid, published by the New Mexican Print and Publishing Co.in Santa Fe, 1882. Pat Garrett tracked down Billy The Kid and killed him on July 14, 1881. Though the New Mexican newspaper said, “…Sheriff Garrett is the hero of the hour,” most people in the area saw him as a villain for having killed a favorite son. Although he had put his life on the line for his community, he lost the next election for sheriff of Lincoln County. Unfortunately, his book didn’t sell well as eight books had already beat him to the press.

Also See:

Billy The Kid – Teenage Outlaw of New Mexico

The Real Billy (author Terri Meeker)

Fort Sumner – Pride of the Pecos

Lincoln, NM – Wild Wild West Frozen in Time

New Mexico’s Lincoln County War

Pat Garrett – An Unlucky Lawman