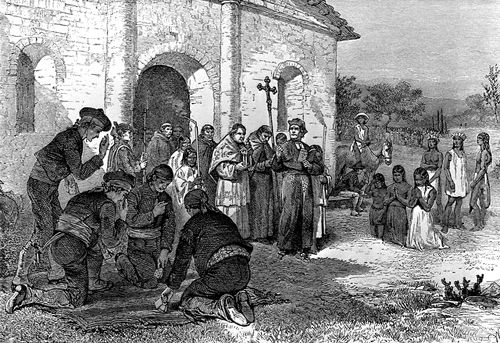

Originally known as the Mission San Antonio de Valero, the Alamo, began as a Catholic mission and compound in 1718, one of many Catholic missions organized as part of the official Spanish plan to Christianize Native Americans and colonize northern New Spain.

The first of five missions to be built in what would become San Antonio was established by Father Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares of the College of Santa Cruz of Querétaroqv, who first visited the region in 1709. In 1716 Olivares received approval from the Marqués de Valero, the viceroy of New Spain (Mexico), for a plan to remove to San Antonio the dwindling mission of San Francisco Solano, founded in 1700 near the right bank of the Rio Grande at the site of present Guerrero, Coahuila.

The viceroy also directed Martín de Alarcón, governor of Coahuila and Texas, to accompany Olivares with a military guard. After considerable delay, Olivares and Alarcón traveled separately to San Antonio in the spring of 1718. The mission was founded on May 1, quickly followed by the San Antonio de Béxar Presidio and the civilian settlement of Villa de Béxar.

The mission, originally located west of San Pedro Springs, survived three moves and numerous setbacks during its early years. After a hurricane destroyed most of the existing buildings in 1724, the mission was re-established on its present site on the east bank of the San Antonio River. Its earliest buildings were of temporary construction but were replaced with more permanent structures throughout the years.

Work began on the stone convento, or priest’s residence, by 1727. Replacing earlier adobe structures, the two-story, arcaded stone building eventually included two wings along the west and south edges of an inner courtyard immediately north of the church. The convento, now known as the long barracks, also housed the friars, offices, kitchen, dining room, and guest rooms.

Over the next several decades, the mission would continue to struggle, continually harassed by hostile Apache Indians and becoming the victim of the smallpox and measles epidemic in 1739, which devastated the Indians of the mission.

However, by the 1740s, the mission’s Indian population began to increase again. In 1744, work on a stone church began. However, there was a flaw in the building plan, as the church, its tower, and the sacristy collapsed in the 1750s.

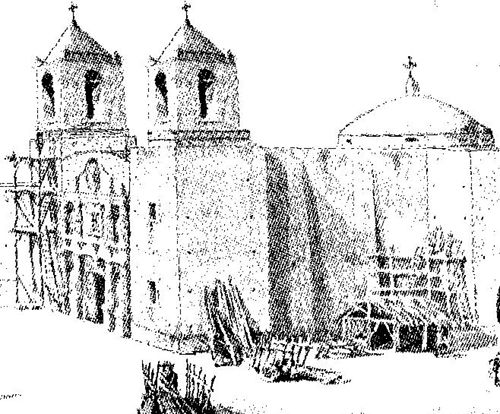

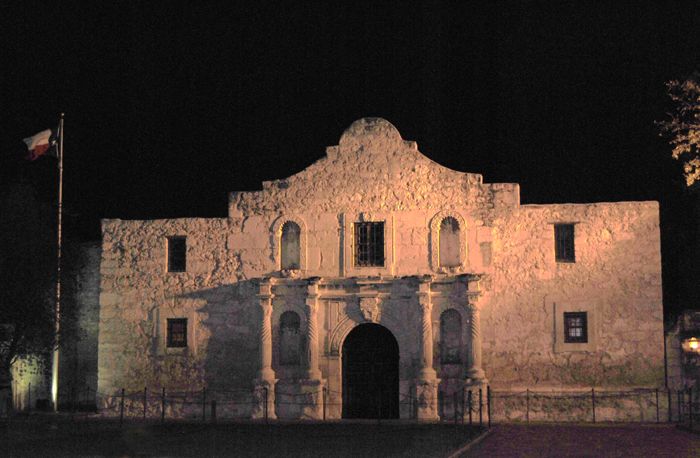

With the mission now serving more than 300 Indians, work on a new church began in 1758 with an ambitious plan. Built in a cross design, it included a sacristy, choir loft, barrel-vaulted roof, twin bell towers, a dome, and an elaborately carved façade. It was constructed of four-foot-thick limestone blocks and was intended to be three stories high. However, as the number of mission Indians declined, work stalled, and the upper-level bell towers and dome never began.

Since the mission church was never finished, it was likely never used for religious services, and mission life probably revolved around the convento. The three-acre mission complex also included storerooms, a granary, workrooms, Indian residences, and an acequia, or irrigation ditch. During the mission’s peak population in the mid-1700s, the complex included about 30 adobe homes and numerous brush huts.

The mission was largely self-sufficient, relying on its 2,000 head of cattle and 1,300 sheep for food and clothing. Additionally, the mission’s farmland produced up to 2,000 bushels of corn and 100 bushels of beans and cotton each year.

In addition to constructing buildings and irrigation ditches, Indians operated weaving, blacksmith, and carpentry shops; cultivated maize, beans, cotton, vegetables, and fruits in outlying fields and orchards; and on the mission ranch, grazed livestock herds numbering hundreds of cattle, sheep, and goats, as well as horses and oxen.

While the objective of the Mission San Antonio de Valero was to focus on the conversion of the Indians to Christianity and produce loyal subjects to the crown, the missionaries were forced to take on another role – that of defense. Though the San Antonio de Bexar presidio was established directly across the San Antonio River to protect the mission, the Spanish government failed to complete or adequately garrison the fortress. Though plans were drawn up to build a wall around the Presidio, they were never completed, and it consisted of a single adobe building with the soldiers living in brush huts. In 1745, about 100 mission Indians successfully drove off a band of 300 Apache, which had surrounded the Presidio.

After the massacre at the Santa Cruz de San Sabá Mission, located in present-day Menard County, in 1758, the missionaries and Indians at the Alamo began to build large walls around the mission, which enclosed the central plaza west of the convento. Eight feet high and two feet thick, with a fortified gate, and a turret with three cannons, the mission was guarded by a small artillery.

In 1773 the Franciscans of Querétaro transferred the administration of San Antonio de Valero and its neighboring missions to the Franciscans of the College of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zacatecas. By 1777, the mission’s Indian population had declined to 44 residents. The following year, the new commandant general of the interior provinces, Teodoro de Croix, thought the missions were largely a liability and began taking action to decrease their influence. In 1778, he ruled that all unbranded cattle belonged to the government. As a result, the mission lost much of its wealth and could not support a larger population of converts.

By 1793, only 12 Indians remained at the mission, and the Spanish government ordered the Mission San Antonio de Valero and the other area missions to be secularized. Its religious offices passed to the nearby diocesan parish of San Fernando de Béxar. At the same time, its lands, houses, supplies, equipment, and livestock were distributed among the remaining Indians and local residents. By that time, the mission Indian population had been so reduced that there were only 12 habitable homes, and the fortress walls had already crumbled.

In the early 19th Century, when Mexico began to fight for its independence from Spain, the old mission would become a strategically important site. In 1803, the site became the quarters for the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras, a company of Spanish Colonial mounted lancers who arrived to bolster the existing San Antonio garrison.

They would remain in San Antonio for the next 32 years integrating into the existing population and becoming involved in the community’s military, civil and political affairs, including the Mexican War for Independence and the Texas Revolution. Officially called La Segunda Compania Volante de San Carlos de Parras (Alamo de Parras), it was from this company of lancers that the mission gained the name of the “Alamo.”

From 1806 to 1812, the convento served as San Antonio’s first hospital, and parts of the mission served as a prison. Mexican soldiers often held the mission during Mexico’s War of Independence with Spain (1810–1821). It was officially transferred to Mexico when the country won its independence and would continue to be held by the Mexicans until December 1835.

By then, the Texians were fighting for their independence from Mexico, and about 100 Texian soldiers manned the Alamo. Led by Colonel James C. Neill, he requested that an additional 200 men be sent to fortify the Alamo. However, the Texian government was in turmoil and unable to provide much assistance. Neill and his men then began to fortify the Alamo the best they could.

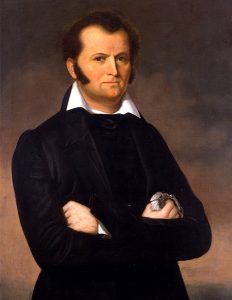

In the meantime, General Sam Houston, believing the Texians did not have the manpower to hold the fort, ordered Colonel James Bowie to take 35–50 men to Bexar to help Neill move all the artillery and destroy the Alamo. However, there were not enough oxen to move the artillery elsewhere, and most men believed the complex was strategically important, so it was not destroyed. Neill then left to pursue additional reinforcements and supplies for the garrison, and William Travis and James Bowie were left to share command of the Alamo.

Before any reinforcements could arrive at the Alamo, the Mexican army, under the command of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, marched on San Antonio de Bexar on February 23, 1836.

For the next 13 days, the Mexican Army laid siege to the city and the Alamo, culminating in a fierce battle on March 6. As the Mexican army breached the walls and began gathering in the Alamo compound’s interior, most Texians returned to the convento and the chapel. Barricaded behind large wooden doors, the Mexicans cannoned the barricades and entered to defeat the Texians. The last to die were eleven men manning two 12-pound cannons in the chapel. The Mexicans then stacked the Texian bodies and burned them. Severely outnumbered, the Texas soldiers had killed some 400-600 Mexicans during the siege.

Afterward, about 1,000 Mexican soldiers remained at the mission, repairing and fortifying the complex. However, after their defeat at the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, and the capture of Santa Anna, the Mexican army agreed to leave Texas, effectively ending the Texas Revolution. When the Mexican army retreated, they tore down many Alamo walls and burned some buildings.

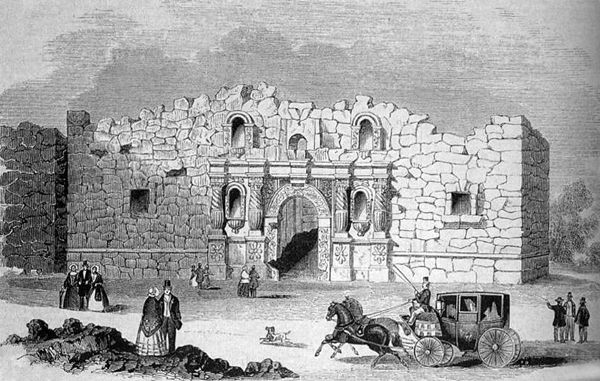

The Texians briefly used the Alamo as a fortress in December 1836 and again in January 1839. The Mexican army regained control in March 1841 and, in September 1842, used the site as they briefly took San Antonio de Bexar. In the meantime, numerous stone carvings had been knocked off the walls, and in 1840, the City of San Antonio allowed local citizens to take stone from the Alamo for $5 per wagonload. By the time Texas was annexed to the United States in 1845, the site stood in ruins, was filled with weeds, grass covered many of the walls, and was inhabited by bats.

A year later, in 1846, the United States Army occupied the site as the Mexican-American War was looming. By the end of the year, they had appropriated part of the Alamo complex for the Quartermaster’s Department, and before long, the convent building had been restored to serve as offices and storerooms. However, the church remained vacant as a three-way title controversy erupted over its title with the City of San Antonio and the Catholic Church. The church’s claim would prevail, and in 1849, the Army began to rent the mission chapel and convento. The army also completed the roofless mission to be used as a headquarters. The complex would eventually house not only the supply depot and headquarters but also storage facilities, a blacksmith shop, and stables.

During the Civil War, Federal troops abandoned the complex, which the Confederate Army soon took over. The United States Army again maintained control over the Alamo when the war was over. Soldiers continued to occupy the site until 1876, when nearby Fort Sam Houston was established. During the Army’s occupation, they repaired the convento.

Private construction during the 1850s obliterated much of the rest of the complex. The mission’s south gate referred to as the “Low Barracks,” served as a jail before being demolished in the late 1860s. The central mission plaza became a public park called the Alamo Plaza, and new businesses were built over the grounds behind the convento. The convento itself was acquired by a local merchant in 1877 and was utilized as a grocery store.

Efforts to preserve the San Antonio de Valero site began during the 1880s, and the site was purchased from the Catholic Church in 1883 by the State of Texas. It was then conveyed to the City of San Antonio to utilize as a museum. Occasional tours were then made at the Alamo, but there were no efforts to restore the structure.

In 1905, the convento was purchased by Clara Driscoll for the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. Later, the Texas legislature approved the purchase of the convento and named the Daughters custodians of both it and the church. A controversy ensued within the group regarding the restoration of the properties, which some called the 2nd Battle of the Alamo. The debate grew so heated that it wound up in the court system, and the State of Texas stepped back in to take control of the property.

When the controversy was finally settled, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas acquired the entire city block behind the surviving mission structures and demolished later buildings to establish a memorial park. Over the years, they worked towards creating a plaza with the chapel as its centerpiece. In 1935, they convinced the city of San Antonio not to place a fire station in a building near the Alamo. It later became the Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library.

During the Great Depression, money from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the National Youth Administration was used to construct a wall around the Alamo, build a museum, and raze several old buildings left on the Alamo property. The remaining one-story walls of the convento remained roofless until refurbished as the Long Barracks Museum in the late 1960s. The Alamo was designated a National Historic Landmark in December 1960 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places when they were founded in 1966. The Alamo Plaza Historic District was also added to the National Register in 1977. Today, the Alamo is one of North America’s finest examples of Spanish missions.

Serving as a museum today, the Alamo welcomes more than four million visitors each year, making it one of the most popular historic sites in the United States.

Contact Information:

The Alamo

300 Alamo Plaza

P.O. Box 2599

San Antonio, Texas 78299

210-225-1391

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

Also See:

Remember the Alamo – The Battle