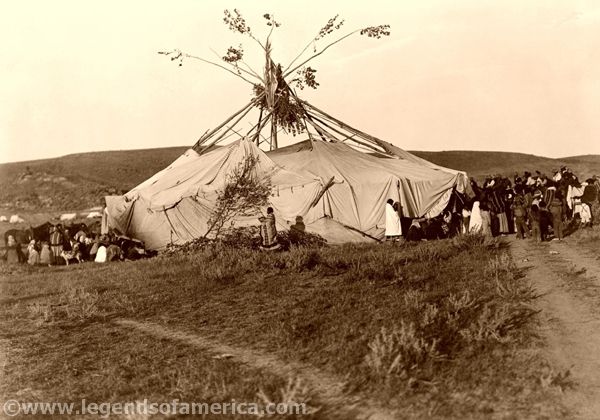

Navajo initiation of a young man.

Initially, an ordeal was a form of trial to determine guilt or innocence; however, the term evolved to be applied to any severe trial or test of courage, endurance, or fortitude. Therefore, the two usages of the term among the North American tribes may be divided into ordeals used to establish guilt and settle differences, and those undergone for the sake of some material or supernatural advantage.

The ordeals corresponding closest to the tests to which the name was applied initially were those undertaken to determine witches or wizards. If it was believed that a man had died in consequence of being bewitched, the Tsimshian tribe would take his heart out and put a red-hot stone against it, wishing at the same time that the enemy might die. If the heart burst, they thought their wish would be fulfilled; if not, they believed their suspicions were unfounded.

A Haida priest would repeat the names of all persons in the village in the presence of a live mouse and determine the guilty party by watching its motions.

A Tlingit suspected of witchcraft was tied up for 8 or 10 days to extort a confession from him, and he was liberated at the end of that period if he was still alive. But, as confession secured immediate liberty and involved no unpleasant consequences except an obligation to remove the spell, few were probably found innocent. This, however, can hardly be considered a real ordeal since the victim’s guilt was practically assumed, and the test was like torment to extract a confession.

Also connected with the ordeals of this class were contests between individuals and groups, for it was supposed that victory was determined more by supernatural than by natural powers. A case is recorded among the Comanche where two men whose ill will toward each other had become so great as to defy all attempts at reconciliation were allowed to fight a duel. Their left arms were tied together, a knife placed in the right hand of each, and they fought until both fell. A Teton myth recorded a similar duel, and the Eskimo practiced similar contests.

In this culture, when two Eskimo groups met for the first time, each party selected a champion, and the two struck each other on the side of the head or the bared shoulders until one gave in. Champions of ancient Eskimo bands, Netchilirmiut and Aivilirmiut, contested by pressing the points of their knives against each other’s cheeks. Such contests were also forced on persons wandering among strange people and were often matters of life and death. Chinook myths speak of similar endurance tests between supernatural beings, perhaps shared by men. Differences between towns on the North Pacific coast were often settled by appointing a day for fighting when the people of both sides arrayed themselves in their hide and wooden armor and engaged in a pitched battle, the issue being determined by the fall of one or two prominent men. Contests between strangers or representatives of different towns or social groups were also settled by playing a game. At a feast on the North Pacific coast, one who had used careless or slighting words toward the people of his host was forced to devour a tray full of bad-tasting food or perhaps to swallow a quantity of urine. Two people often contested to see which could empty a tray the more expeditiously.

Ordeals of the second type covered the hardships placed upon a growing boy to make him strong, the fasts and regulations to which a girl was subjected at puberty, and those which a youth underwent to obtain supernatural helpers, as well as the solitary fasts of persons who desired to become priests or medicine men who desired greater supernatural power. These endurance tests were especially applicable to the fasts and tortures undergone in preparation for ceremonies or during initiations into secret societies.

Initiation into the mysteries of the tribe occurred around puberty and varied greatly from tribe to tribe. When old enough to receive the religious mysteries, Pueblo children underwent ceremonial flogging. Similarly, the Alibamu and other Indian tribes of the Gulf states would require the children to pass through a group that whipped them until they drew blood.

The Huskanaw was an ordeal among Virginia Indians undertaken to prepare youths for the higher duties of manhood. It consisted of solitary confinement and emetics, “whereby remembrance of the past was supposed to be obliterated, and the mind left free for the reception of new impressions.” Among those tribes in which individuals acquired supernatural helpers, a youth was compelled to go out alone into the forest or the mountains for an extended period, fast there, and sometimes take certain medicines to enable him to see his guardian spirit.

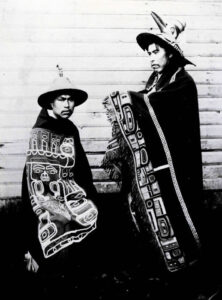

Similar were the ordeals that chiefs among the Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and other North Pacific coast tribes underwent when they sought to increase wealth, achieve success in war, or attain a long life. It was also practiced by priests and medicine men who wished to increase their powers. At such times, they chewed certain herbs to help them see the spirits. The use of the “black drink” by Muskhogean tribes was with a similar intent.

While undergoing initiation into a secret society on the North Pacific coast, a youth fasted and, for a specific period, disappeared into the woods to commune with the society’s spirit in complete solitude. Anyone discovering a Kwakiutl youth at this time could slay him and obtain the secret society privileges in his stead. On the plains, the principal participants in the Sun Dance had skewers run through the fleshy parts of their backs, to which thongs were attached and fastened at the other end of the Sun Dance Pole. Sometimes a person was drawn up so high that he barely touched the ground, and afterward would throw his weight against the skewers until they tore their way out. Another participant would have the thongs fastened to a skull, which he pulled around the entire camping circle; no matter what obstacles impeded his progress, he was not allowed to touch either the thongs or the skull with his hands.

During the Hidatsa ceremony of Naxpike, a variant of the Sun Dance, devotees ran arrows through the muscles in different parts of their bodies. On one occasion, a warrior is known to have tied a thirsty horse to his body utilizing thongs passed through holes in his flesh, after which he led him to water, restrained him from drinking without touching his hands to the thongs, and brought him back in triumph. The extraordinary ordeal of a Cheyenne society was walking barefoot on hot coals.

A person initiated into the Chippewa and Menominee society of the Midewiwin was “shot” with a medicine bag and immediately fell on his face. Making him fall on his face, a secret-society spirit, or the guardian spirit of a northwest coast priest, also made itself felt. When introduced into the Omaha society called Washashka, one was shot in the Adam’s apple by something said to be taken from an otter’s head. As part of the ceremony of initiation among the Hopi, a man had to take a feathered prayer stick to a distant spring, run all the way, and return within a specific time; and chosen men of the Zuni were obliged to walk to a lake 45 miles distant, clothed only in the breech-cloth and so exposed to the rays of the burning sun, to deposit plume-sticks and pray for rain. Among the same people, one of the ordeals to which an initiate into the Priesthood of the Bow was subjected was to sit naked for hours on a large ant hill, his flesh exposed to the torment of myriads of ants. At the time of the winter solstice, the Hopi priests sat naked in a circle and suffered gourds of ice-cold water dashed over them.

Specific regulations were also enforced before war expeditions, hunting excursions, or the preparation of medicines. Medicines were generally compounded by individuals after fasts, abstinence from women, and isolation in the woods or mountains. Before going to hunt, a party leader fasted for a certain length of time and counted off so many days until one arrived, which he considered his lucky day. On the northwest coast, the warriors bathed in the sea in wintertime, after which they whipped each other with branches, and until the first encounter took place, they fasted and abstained from water as much as possible. Elsewhere, warriors sometimes spent time in the sweat lodge. Among the tribes of the east and some others, prisoners were forced to run between two lines of people armed with clubs, tomahawks, and other weapons, and only those who survived to reach the chief’s house or another particular mark had their safety preserved.

The objective behind most tortures was to break down the victim’s self-command and extort some indication of weakness from him, while the victim aimed to show an unmoved countenance, flinging back scorn and defiance at his tormentors until the very last.

By the Bureau of Ethnology, 1906. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 025.

About the Author: The foregoing is from the Handbook of American Indians, an extensive four-volume work published by the Bureau of Ethnology in 1906. This work was compiled by some of the best-known Indian researchers from 1873 to 1905 and edited by Frederick W. Hodge, an anthropologist, archaeologist, and historian who worked for the bureau. Though the content is basically the same, it is not verbatim, as it has been heavily edited for the modern reader.

Also See: