The Navajo call themselves Dineh, which means “The People” in the Navajo language. Closely related to the Apache, the Navajo are an Athapascan-speaking people who migrated from west-central Canada to the Southwest around the 15th century.

By the time Spanish explorers encountered the Navajo in the 16th century, trade had been established for some time between the Pueblo peoples and the Navajo, exchanging maize and woven cotton goods for buffalo meat, hides, and materials for stone tools.

Because they hunted buffalo, lived in tents, and used dogs to pull travois loaded with their possessions, the Spanish referred to them as “dog nomads.”

When Francisco Vasquez de Coronado first observed the Athapascan-speaking people, they were wintering near the pueblos in established camps. Coronado reported the modern Western Apache area as uninhabited, and other Spaniards first mentioned Apache living west of the Rio Grande in the 1580s.

In April 1541, Francisco Coronado wrote of them:

“After seventeen days of travel, I came upon a rancheria of the Indians who follow these cattle [buffalo]. These natives are called Querechos. They do not cultivate the land but eat raw meat and drink the blood of the cattle they kill. They dress in the skins of the cattle, with which all the people in this land clothe themselves, and they have very well-constructed tents made with tanned and greased cowhides, in which they live and take along as they follow the cattle. They have dogs that they load to carry their tents, poles, and belongings.”

The Apache group of the Athapaskans most likely moved to their southwestern homelands in the late 16th and early 17th centuries; the Navajo did not expand their range until the 17th century, occupying areas the Pueblo peoples had abandoned during prior centuries.

The Spanish first specifically mentioned the “Apachu de Nabajo” (Navajo) in the 1620s, referring to people in the Chama region east of the San Juan River. By the 1640s, the term was applied to Athapaskan peoples from the Chama on the east to the San Juan on the west.

As the Navajo people moved into the Southwest, they learned farming techniques from the Puebloan peoples. Soon, they settled down from a hunting-gathering society to an agricultural, ranching, and ceremonial society.

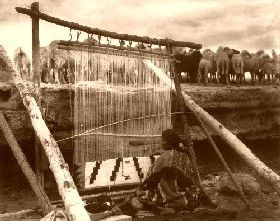

The Puebloans also taught them rituals, songs, prayers, and stories. Later, when the Navajo acquired sheep and horses from the Spaniards through trading or raiding, they created entire ceremonies that included songs and prayers about sheep and horses. Sheep also provided wool, which allowed the People to become great weavers of blankets and rugs.

In the late 18th century, the Navajo migrated west to the present-day Four Corners area, where they established Canyon de Chelly as their stronghold. The move was prompted by hostile pressures from the Spaniards to the south, the Comanches to the east, and the Ute to the north.

Whenever possible, the People retreated rather than fought, and they made no exception in this case. During this time, the Navajo became prosperous materially, artistically, and ceremonially—a development that led Nathaniel Patton to write in the Missouri Intelligencer in 1824 that the Navajo were superior to the Plains Indians because they fashioned clothes, designed jewelry, raised livestock, and cultivated land.

In 1846, American troops moved into the Southwest during the Mexican War. Between this time and 1863, several treaties were signed and subsequently broken with the Navajo.

As more and more Americans settled in the territory of New Mexico, they met increasingly fierce resistance from the Mescalero Apache and Navajo people, who fought to maintain control of their traditional lands and their way of life.

To subjugate them, the U.S. Army made war on the Mescalero Apache and Navajo Indian tribes, destroying their fields, orchards, houses, and livestock. Before the Indians were even defeated, Congress authorized the establishment of Fort Sumner at Bosque Redondo on October 31, 1862, a space 40 miles square. It was to be the first Indian reservation west of Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The plan was to transform the Apache and Navajo into farmers on the Bosque Redondo, utilizing irrigation from the Pecos River. They were also to be “civilized” by attending school and practicing Christianity.

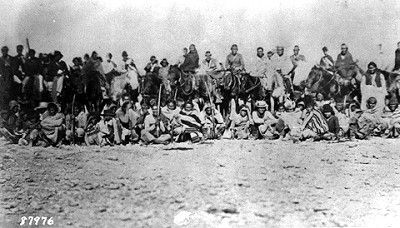

The Apache and Navajo, who had survived the army attacks, were then starved into submission and forced to march to the Bosque Redondo Indian Reservation near Fort Sumner, New Mexico. In the case of the Navajo, 8,500 men, women, and children were marched almost 300 miles from northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico to Bosque Redondo, a desolate tract on the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico. Traveling in harsh winter conditions for almost two months, about 200 Navajo died of cold and starvation. More died after they arrived at the barren reservation. The forced march, led by Kit Carson, became known by the Navajo as the “Long Walk.”

Most of the Mescalero Apache eluded their military guards and abandoned the reservation on November 3, 1865, but, for the Navajo, another three years passed before the United States Government recognized that their plan for Americanizing the People had failed. The Navajo were finally acknowledged as sovereign in the historic Treaty of 1868.

The Navajo returned to their land along the Arizona-New Mexico border hungry and in rags. Though their territory had been reduced to an area much smaller than what they had occupied before the departure to Bosque Redondo, they were one of the few tribes that were allowed to return to their native lands. The U.S. government issued them rations and sheep, and within a few years, the Navajo multiplied their livestock numbers.

When the railroad arrived in 1880, traders and the Navajo exchanged maize, wool, mutton, hides, livestock, and crafts for food and manufactured goods. In 1922, a business council was established to negotiate leases for natural resources located on the reservation, including oil, natural gas, timber, uranium, and coal. This council eventually evolved into the Navajo Nation Council, which now governs the Navajo Nation.

Navajo – The Vanishing Race, by Edward S. Curtis.

Today, the Navajo Nation Reservation, which includes 27,000 square miles of land, is the largest in the United States. With over 250,000 members, most of whom still reside on Navajo land, stretching across the Colorado Plateau into Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. The government seat is in the town of Window Rock, Arizona.

The Navajo Nation has built a modern economy on traditional endeavors, including sheep herding, fiber production, weaving, jewelry making, and art trading. Newer industries that employ members include coal and uranium mining, though the uranium market slowed near the end of the 20th century. The Navajo Nation’s extensive mineral resources are among the most valuable in the United States, and Native American nations hold them. The Navajo government employs hundreds in civil service and administrative jobs. Other Navajo members work at retail stores and other businesses within the Nation’s reservation or nearby towns.

For more information, please visit the Navajo Nation Government website.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

See our Navajo Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

Navajo Long Walk to the Bosque Redondo

Apache – Fiercest Warriors in the Southwest

Native American (main page)

See Sources.