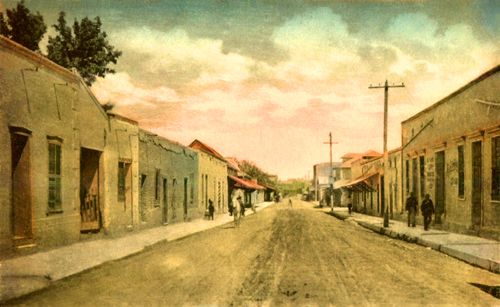

Tucson, Arizona

By James Harvey McClintock in 1913.

In Tucson in 1873, the people began to appreciate that lax enforcement of the law on the part of county officials made possible the escape of too many desperate criminals. So, on August 8, the population rose, more or less en masse, and took from the county jail and hanged John Willis, Leonard Cordova, Clemente Lopez, and Jesus Saguaripa. A coroner’s jury summoned commended the executioners and stated that “such extreme measures seem to be the inevitable result of allowing criminals to escape the penalties of their crimes.” Willis had been found guilty of killing Robert Swoope at Adamsville in the course of a drunken discussion of the shooting of Colonel Kennedy by John Rogers, whose own fate seems to have escaped local historians.

The three Mexicans, for plunder, had murdered in Tucson one of their own countrymen and his wife. The execution was without secrecy upon a common gibbet erected before the jail door after the condemned men had been given the benefit of clergy.

The people of the young town of Safford in August 1877 took the law into their own hands and hanged Oliver P. McCoy, who had acknowledged the killing of J.P. Lewis, a farmer. McCoy was to have been taken to Tucson for trial, and there was fear of miscarriage of justice in the courts.

In December 1877, the people of the small village of Hackberry in Mohave County hanged Charles Rice, charged with the murder of Frank McNeil. His offense seems to have been the disarming of Rice’s friend, Robert White, in the course of an altercation in which White appeared to be in the wrong. About the time of the hanging, White, fearing a similar fate, tried to escape and was shot down and killed by his guards.

At Saint John’s, in the fall of 1881, was a summary execution, a gathering of citizens taking from the jail and hanging Joseph Waters and William Campbell. They had killed David Blanchard and J. Barrett at the Blanchard Ranch. It was told that the men hanged had been hired to do the murder by someone who wanted the ranch as a trading post. But nothing was done with the third party.

April 24, 1885, popular judgment was executed five miles below Holbrook, where two murderers from the town, Lyon and Reed, were run into the rocks by a posse of citizens headed by James D. Houck and killed. The couple had killed a man called Garcia.

Holbrook, Arizona in 1900.

One of the most serious criminal episodes in Yuma was early in 1901 when Mrs. J.J. Burns, a farmer’s wife, was shot and killed by a Constable, H.H. Alexander, who had been charged with the service of a legal paper. About two months after the shooting, Alexander was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. April 9, while being taken from the courthouse to the territorial penitentiary, walking between two officers, Alexander dropped dead, killed by a rifle bullet from the window of a building nearby. It was assumed that a relative of the King family (to which Mrs. Burns belonged) had assumed the fullest degree of vengeance, but the matter was taken no further.

Inside the 1898 Navajo County Jail in Holbrook. Photo by Jim Hinckley.

In December 1899, the county jail at Holbrook had a notable prisoner, George Smiley, convicted of the killing of a section foreman named McSweeney. The sheriff at that time was F.J. Wattron, a school teacher/editor, who thought to make the first legal execution in the new County of Navajo a sort of social gathering. So he issued a cordial gilt-bordered invitation to visitors, assuring those invited that the latest improved methods in the art of scientific strangulation would be employed and everything possible would be done to make the surroundings cheerful and the execution a success. There were hundreds of protesting letters over the sheriff’s levity. Governor Murphy waxed indignant, scored the sheriff for flippancy, and granted the prisoner a month’s reprieve. Smiley was hanged on January 8, 1900.

Commodore Perry Owens was one of the most famous frontier sheriffs, whose particular field was Northeastern Arizona. He looked the part of the frontier sheriff with long hair down his back, a large hat, and high boots, carrying at least one large revolver. What gave him more than local celebrity was a fight in 1886 in Holbrook in which he killed three cowboys and wounded a fourth.

At that time, Holbrook was still included within Apache County, of which Owens was sheriff. One Andy Cooper had a few head of cattle in Pleasant Valley. He had a bad reputation with stockmen and had been accused of stealing cattle and horses on numerous occasions. Still, the fellow had been canny in his operations, and never could there be gathered together evidence enough to convict. Finally, the Apache County grand jury found an indictment against him, but the evidence was lacking. The district attorney advised the sheriff that the indictment had been found more like a scare than anything else.

On the day of the killing, Cooper was in Holbrook visiting his mother at a time when the sheriff also happened to be in town. He was advised of Cooper’s presence by several saloon loungers.

When Owens showed no inclination to make the arrest, he was baited by the crowd, and he finally lost patience. He rode to the house of Cooper’s mother, Mrs. Blevins, dismounted about 30 feet in front of the house, and walked up to the house. He knocked on the door, and when he identified himself, the door was slammed in his face. He began backing up toward his horse when the house door opened, and a rifle ball sang just past his head and killed his horse. Owens fired before the door closed, shooting his would-be murderer through the shoulder. The man he had just shot was John Blevins, Cooper’s half-brother. At almost the same instant, Cooper’s face was seen peering over the sill of a window. Owens immediately fired through the boards of the house, shooting Cooper through the lower part of the body. A third cowboy named Roberts was seen stealing around from the rear of the house, with a revolver held over his head, ready to fire. Owens shot him in the back as he turned around, and though he dragged himself to a back room, he was dead in ten minutes. Then, young Blevins, a lad of only 16. appeared through the same front door where the first shot had been fired. Clinging to him was his mother, shrieking and trying to hold him back; the half-crazed lad was dropping his pistol to shoot when Owens sent a bullet through his heart.

One of the most lurid dime novel bandits the Southwest ever knew was Augustine Chacon, captured near the international line by Ex-Captain Mossman of the Arizona Rangers. They had a personal interest in landing the desperado. Chacon murdered a Mexican in Morenci in 1895 and was sentenced to hang. He escaped from jail a few days before his execution and later was charged with the murder of two prospectors on Eagle Creek and of an old miner whose body was found in an abandoned shaft. He then joined Burt Alvord and other outlaws in Sonora and participated in at least one train robbery. Chacon, after his arrest, was duly hanged at Solomonville in December 1902.

In the list of desperadoes of the early days, a place should be reserved for a blacksmith named Rodgers who, at the Santa Rita mines in 1861, boasted of having killed 18 people and produced a string of human ears to prove his tale. At the time, he promised that he would make the number twenty-five before he quit. In this ambition, he later killed six men at El Paso, where he was caught, and in an endeavor to make the punishment fit the crime, he was hanged by the heels over a slow fire — and his own ears made the twenty-fifth pair.

Yuma, Arizona old Territorial Prison

The first legal execution in Yuma County occurred in 1873, and was that of Manuel Fernandez, hanged for the murder of D.A. McCarty, generally known as “Raw Hide.” The crime was committed for loot, and before it was discovered, the Mexican and his confederate had worked several nights carrying wagonloads of goods away from their victim’s store.

A rather noted criminal was Joseph Casey, hanged in Tucson on April 15, 1884. He was a deserter from the regular army. He had been charged with several murders and other criminalities along the border, finally being arrested in 1882 for cattle theft. On October 23, he and three men, held on a charge of murder, and five other prisoners broke out of jail at Tucson, but Casey, six months later, was re-arrested at El Paso. On April 29, 1883, again, an inmate of the Tucson jail killed jailer A.W. Holbrook in a second escape. A mob tried to get him out to hang him, but there was swift retribution, and he was soon sentenced by Judge Fitzgerald to capital punishment and was duly hanged.

A notable execution occurred at Tombstone late in 1900 in the hanging of the two Halderman brothers, found guilty of the murder of Constable Chester Ainsworth and Teddy Moore at the Halderman ranch in the Chiricahua Mountains. The brothers had been arrested on a charge of cattle stealing by Ainsworth and Moore and had been allowed to enter their home to secure clothing. Instead, they reappeared with rifles and shot the officers from their horses. The murderers fled but were captured near Duncan by a sheriff’s posse and returned for trial at Tombstone.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2022.

Notes and Author: James Harvey McClintock was born in Sacramento in 1864 and moved to Arizona at the age of 15, working for his brother at the Salt River Herald (later known as the Arizona Republic). When McClintock was 22, he began to attend the Territorial Normal School in Tempe, where he earned a teaching certificate. Later, he would serve as Theodore Roosevelt’s right-hand man in the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War and become an Arizona State Representative. Between 1913 and 1916, McClintock published a three-volume history of Arizona called Arizona: The Youngest State (now in the public domain,) in which this article appeared. McClintock continued to live in Arizona until his poor health forced him to return to California, where he died on May 10, 1934, at the age of 70.

Note: The article is not verbatim as spelling errors, minor grammatical changes have been made, and the text updated for the modern reader..

Also see: