The Yokuts, also called Mariposan, a name derived from present-day Mariposa County, are native to central California.

Yokuts means “person” or “people.” Members of the Penutian language family. They occupied a strip about 250 miles long on the floor of San Joaquin Valley from the mouth of the San Joaquin River to the foot of Tehachapi Mountains and the adjacent lower slopes or foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, up to an altitude of a few thousand feet, from the Fresno River south. In the northern half of the Yokuts region, some tribes inhabited the foothills of the Coast Range to the west, where there is evidence they inhabited the Carrizo Plain and created rock art in the Painted Rock area. The Yokuts are sometimes divided into the Southern Valley Yokuts, the Northern Valley Yokuts, and the Foothill Yokuts.

Having numerous dialects, the Yokuts were comprised of as many as 60 separate hunter-gatherer tribes, speaking several related languages. They lived in many villages with up to 350 people in each tribe. Every tribe has a Head Chief, a sub-chief called Winatun, and a Village Chief.

Chiefs were generally wealthy and knowledgeable in religious matters. The chiefly office was hereditary and could be held by women and men. The chief sponsored ceremonies hosted guests, aided the poor, mediated disputes, authorized hunts as well as the execution of evil people such as sorcerers. Two other important offices were those of jester, or clown, and of an undertaker. The latter was usually a male-to-female two-spirit person who adopted the gender identity opposite their biological attributes and lived as that gender for the rest of their lives. Another office included the chief’s messenger.

Families arranged marriages with the couple’s consent. Polygamy was socially acceptable among the Yokuts, but it was rarely practiced. After living with the woman’s parents for a year, a couple lived in or near the husband’s parents’ home. The Yokuts observed parent-in-law taboos, meaning a son-in-law and mother-in-law never spoke directly to one another, and a daughter-in-law never spoke directly to her father-in-law. Divorce was not difficult within the tribe and could be achieved for reasons such as affairs, laziness, and infertility.

There were several Yokuts Bands:

Chaushila (Chowchilla)

Choinumni

Chukchansi

Gashowu

Lakisamni

Tachi

Wukchumni

In Yokuts culture, men usually did the hunting, fishing, and building. They used spears, basket traps, and other tools for hunting animals. Lake trout, perch, chubs, suckers, salmon, and steelhead were caught in the lakes and rivers. Waterfowl such as geese, ducks, and mud hens were caught with snares in the tule marshes. The Yokuts enjoyed mussels and turtles as food. Antelope, elk, and deer were killed when they came to the lakes to drink. Other animals and birds that were eaten included wild pigeons, quail, rabbits, squirrels and other rodents, and dogs.

The women gathered, maintained the home, and cared for the children. Their staple food was derived from acorn mash, though they also gathered tule roots and iris bulbs to make flour. Other foraged food included manzanita berries, pine nuts, and seeds. Salt came from salt grass. They also cultivated tobacco.

Bows and arrows were used in hunting and in warfare. Though the Yokuts made some bows and arrows, others were gained through trade with other groups. The bows were backed with sinew, and the arrows had feathers. Other animals were caught with traps and snares made from branches and brush. Fish traps were set up across streams. Spears were also used for fishing. Some birds were caught with nets made from milkweed fibers. An important tool was the one with which the hot stones were removed from the cooking basket. This was a stick about 30 inches long with a loop at one end, used to stir the mush and lift the stones.

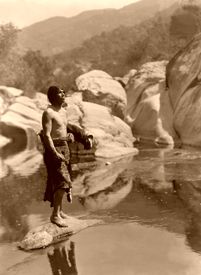

The Valley Yokuts had canoe-shaped rafts made from tule reeds tied together in bundles that were often large enough to hold six people. They were pushed with long poles. The Foothill Yokuts made rafts by lashing together two logs.

Wood and stone were not as plentiful in the San Joaquin Valley as in many parts of California. Obsidian for knives and arrowheads was garnered in trade from the north and mountain areas. When obsidian was unavailable, other stones like chert, jasper, and quartz were used to make knives and scrapers. Pieces of animal bone were sharpened to make awls; pointed tools were used to punch holes, and needles for sewing.

Tule reeds made many items, including baskets, cradles, and mats. They also made baby cradles, bowl-shaped cooking baskets, cone-shaped carrying baskets, flat basket trays, seed beaters, and water baskets. Some Foothill Yokuts made rough pottery bowls.

Men wore a piece of deerskin around their hips or went without clothes. Both rabbit skins and mud hen skins were used to make robes, which the people wore around their shoulders when the weather was cold. The Yokuts wore moccasins of deer or elk skin on their feet only when walking in rough country. Yokut women wore a skirt made in two pieces, a narrow fringed part in the front and a larger piece in the back. The skirts were made of tule reeds, marsh grass, or rabbit skins. They also wore a basket cap on their heads when carrying a burden basket, which was held on by a forehead strap.

The Yokuts lived in permanent houses most of the year, leaving only in the summer for trips to gather food. Single families usually made oval-shaped houses, framed with side poles tied to a central ridge pole and covered with tule mats. The Southern Valley tribes often built larger houses for as many as ten families. These houses had steep roofs, with roofs and walls covered with tule mats. In the large house, each family had a fireplace and a door. However, no walls separated one family from another. Houses in the foothills and dry valleys were sometimes built with the floor dug down a foot or two into the ground. In marshy areas, the floor was level with the ground. Both Valley and Foothills Yokuts put up shade roofs like porches outside their houses so that they could work outside.

Each village had a sweathouse, dug down into the ground and covered with brush and earth. Only men used them. Southern Valley Yokuts did not have dance or assembly houses, though these may have been used in Northern Valley villages.

The Yokuts had two important religious ceremonies, including the annual mourning rite and the first fruit rite. Yokuts ceremonies also included puberty rites, which for boys involved using the hallucinogen toloache, made from the jimsonweed (Datura stramonium). Many Yokut dances and ceremonies were held outside, with brush fences surrounding the dance area. Eagle feathers were an important part of the ceremonial decoration. Eagle down was used to make ceremonial skirts. Tall headdresses were made using the tail feathers of magpies around a base of crow feathers.

Shamans — medicine men, were important as they were believed to have supernatural powers, helped conduct ceremonies, and were able to treat the sick. Their power was derived from spirit animals via dreams or vision quests. They cured and presided over ceremonies and charged large fees for cures. Shamans could use their power for good or evil, and if they used it in ways that dissatisfied the tribe, they could be executed.

Artistic expression among the Yokuts included music, singing, painting, and extensive basket weaving, which included designs and images in the baskets. They also utilized tattooing and piercings. Some women had tattoos on their chins.

The Yokuts had several trading routes and traded with the coastal peoples, such as the Chumash tribe. They traded salts, soap stones, and obsidian and used marine shells for money they called keha, showing they had a functional monetary system. With these, they traded for plant and animal products, mussels, and abalone shells, and with the Miwok for baskets, bows, and arrows.

The first time the Yokuts encountered Europeans was in 1772 when Spanish troops were in the area searching for soldiers.

The first to estimate pre-contact population estimates of the Yokuts put them at 18,000 in 1770. However, later estimates suggested that the total should be substantially higher — numbering about 70,000, one of the highest regional population densities in pre-contact North America.

In the 19th century, the Spanish established missions, and as they expanded, they forced the Yokuts to work the land for farming. The harsh working conditions, along with disease and abuse, led to the death of many Indians. With their workforce dwindling, the missions moved further inland, forcing those they encountered to convert and work.

In 1833, malaria was brought by British fur traders, spreading through the native population through their use of sweathouses.

After acquiring California from Mexico after the Mexican-American War, the federal government signed the first state-wide treaty, setting aside seven and a half percent of California’s land area for proposed Indian reservations. This was the first of 18 proposed treaties, of which the U.S. Senate failed to ratify any.

Gold was discovered in California in 1849. The 1850s were a devastating time for Yokuts, which American gold prospectors and settlers almost destroyed. In 1853 malaria spread once again among the Yokuts, killing more natives.

The newly-organized state government took a different approach. In 1851, California Governor Peter Burnett said that unless the Indians were moved east of the Sierras, “a war of extermination would continue to be waged until the Indian race should become extinct.”

By 1854 what was left of the Yokuts tribe was forced to move to the Fort Tejon Reservation. A few years later, the reservation was attacked by white vigilantes who killed most of the inhabitants, and by 1859 the reservation was completely abandoned.

In the next decades, settlers and eventually the California State Militia would wage war against the Yokuts and other native tribes in what became known as the Californian Genocide. The Yokuts were reduced by about 93% between 1850 and 1900, with many survivors being forced into indentured servitude sanctioned by the California State Act for the Government and Protection of Indians.

The Tule reservation was established in 1873, and many Yokuts moved to the reservation. Yokuts found minimal employment in the logging industry as ranch hands and farm laborers into the 20th century. Their children were forcibly sent to boarding schools in the early part of the century.

Disease, violence, and relocation severely diminished the Yokuts population so much that today their numbers do not even come close to what they once were. In 1910, the Yokuts had an estimated population of 600. The Santa Rosa Rancheria was established in 1921.

The census of 1930 showed a population of 1,145.

By the 1950s, most Indian children were enrolled in segregated public schools. A cultural revival took place beginning in the 1960s.

In 1990, about 1,150 Yocut Indians lived on two Yokuts rancherias.

As of the 2010 census, there were a total of 6,273 people who identified as Yokuts. Many live on reservations with casinos, which are essential in providing the Yokuts with jobs, money. and healthcare. The most prominent tribe is the Tachi, which is federally recognized.

Contemporary Yokut tribes Include:

Santa Rosa Rancheria (Tachi)

Picayune Rancheria of Chukchansi Indians

Table Mountain Rancheria (Mono)

Tejon Indian Tribe of California

Tule River Indian Tribe of the Tule River Reservation

Tuolumne Rancheria

The contemporary Wukchumni and Choinumni communities are not yet federally recognized.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Indigenous Americans Long Path to U.S. Citizenship

Native Americans – The First Owners of America

Native American Photo Galleries

Sources:

AAA Native Arts

Encyclopedia Britannica

Social Studies Fact Cards

Wikipedia