Indian Citizenship Act of 1924

If you were born in the United States, you might be blind to the past struggles of others who lived here their entire lives and were treated as foreigners. But it was a long time from our nation’s founding and its principles of freedom before its first occupants were recognized as citizens on a mass scale. And even longer before our indigenous population fully gained the right to vote.

The Choctaw were removed west of the Mississippi River starting in 1831, painting by Alfred Boisseau, 1846.

There were some early examples of Indian citizenship. For instance, in 1831, the Choctaw of Mississippi became citizens with the ratification of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Under that treaty, any Choctaw who elected not to move to Native American Territory could become an American citizen when he registered and if he stayed on designated lands for five years after treaty ratification.

In the U.S. Supreme Court Dred Scott v Sanford decision of 1857, justices said that Native people could become citizens. However, their acquisition of citizenship was by way of naturalization and not by birth within the United States.

Congress addressed the issue of citizenship with the 14th Amendment, passed in 1866 and ratified by the states in 1868. Section 1 reads:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The word “jurisdiction” led many to interpret the amendment to exclude Native Americans. To further that argument, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee stated that the 14th has no effect whatever upon the status of the Indian tribes within the limits of the United States. To them, it was a matter of taxation. The Civil Rights Act of 1866, which survived President Andrew Johnson’s veto, and was passed in 1870, stated – “all persons born in the United States, and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.” If the government didn’t tax you, you weren’t a citizen. At this time, only 8% of the Native American population qualified. Others gained citizenship through marrying someone white, serving in the military, or accepting land allotments taxed by the government.

This exclusion was further cemented into law when, in 1884, the Supreme Court held that a Native person born a citizen of a recognized tribal nation was not born an American citizen and did not become one simply by voluntarily leaving his tribe and settling among whites. They explained that a Native person “who has not been naturalized, or taxed, or recognized as a citizen either by the United States or by the state, is not a citizen of the United States within the meaning of the first section of the Fourteenth Article of Amendment of the Constitution.”

In 1887, the Dawes Severalty Act, as part of an effort to turn Indians into farmers, thus assimilating them into white culture, allowed the federal government to redistribute tribal lands to heads of families in 160-acre allotments. Unclaimed or “surplus” land was sold, and the proceeds were used to establish Indian schools where Native American children learned reading and writing, along with white culture and social systems. While noble with intent by those who opposed the reservation system, over the following decades, the sale of unclaimed land and allotted acreage resulted in the loss of two-thirds of the 138 million acres that Native Americans had held before the Dawes Act.

Fast forward to 1924. Republican Representative, Homer Snyder of New York, proposed legislation to grant citizenship on a broader scale to the indigenous population, in part to recognize Native Americans who had served in World War I. By this time, many natives had become citizens through other means, but not if they still lived the reservation life.

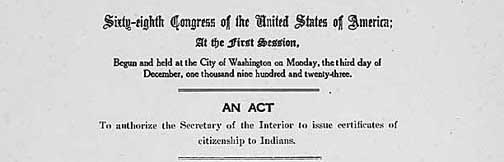

The Indian Citizenship Act, passed by Congress in December of 1923 and signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge on June 2, 1924, reads:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be. They are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided, That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.

The Act’s grant of citizenship applied to approximately 125,000 Indigenous Americans out of the 300,000 at the time. The rest of them had become citizens through other means.

In addition to extending citizenship to Native Americans, the Secretary of the Interior commissioned the Institute for Government Research to assess the impact of the Dawes Act of 1887. Completed in 1928, the Meriam ReportExternal described how government policy oppressed Native Americans and destroyed their culture and society. The poverty and exploitation resulting from the paternalistic Dawes Act spurred the passage of the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act. This legislation promoted Native American autonomy by prohibiting allotment of tribal lands, returning some surplus land, and urging tribes to engage in active self-government. Rather than imposing the legislation on Native Americans, individual tribes were allowed to accept or reject the Indian Reorganization Act. With the aid of federal courts and the government, over two million acres of land were returned to various tribes.

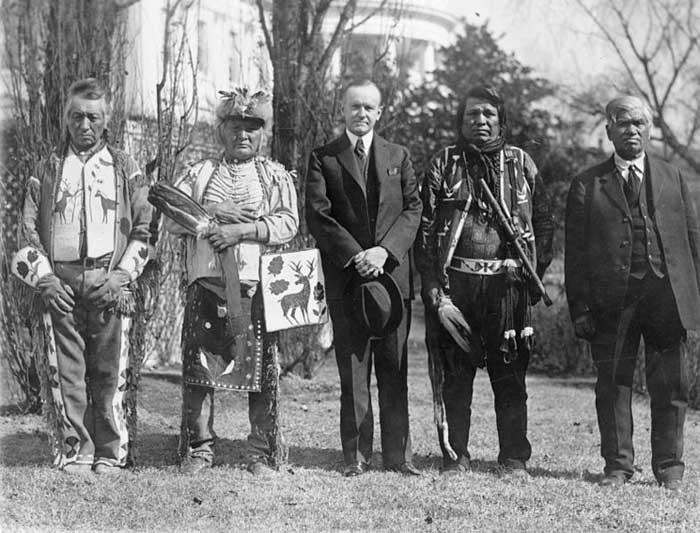

President Calvin Coolidge with four Osage Indians after Coolidge signed

the bill granting Indians full citizenship in 1924.

So, based on the citizenship act of 1924, Native Americans, now U.S. Citizens, could vote, right? Actually, no. The states still governed the right to vote, and several refused to grant that right based on tribes’ exemption from real estate taxes, maintenance of tribal affiliation, and the notion that Indians were under guardianship or lived on lands controlled by federal trusteeship. In 1938, seven states still didn’t recognize indigenous citizen votes.

In 1948, all but two states with the largest Indian populations had extended voting rights to Natives. That year Arizona and New Mexico followed after the Arizona Supreme Court struck down a provision of its state constitution that kept Indians from voting. It wouldn’t be until 1957 that all U.S. States extended the right.

Civil Rights March, Washington, D.C., by Warren K. Leffler, 1963

Even then, Native Americans suffered much of the same shenanigans that kept Black citizens from voting. With the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and subsequent legislation, voting protections were reaffirmed and strengthened for all Americans.

©Dave Alexander, Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

The United States Constitution

The United States Bill of Rights

Native Americans – The First Owners of America

Women’s Suffrage in the United States

Sources: