A cloud passed over the speaker’s face for a moment as he continued:

“And there was a cause of quarrel between us which people around here don’t know about, One of us had to die, and the secret died with him.”

“Why did you not wait to see if your ball had hit him? Why did you turn round so quickly?”

The scout fixed his gray eyes on mine, striking his leg with his riding-whip, as he answered, “I knew he was a dead man. I never miss a shot. I turned on the crowd because I was sure they would shoot me if they saw him fall.”

“The people about here tell me you are a quiet, civil man. How is it you get into these fights?”

“D—-d if I can tell,” he replied, with a puzzled look which at once gave place to a proud defiant expression as he continued – “but you know a man must defend his honor.”

“Yes, I admitted, with some hesitation, remembering that I was not in Boston but on the border and that the code of honor and mode of redress differ slightly in the one place from those of the other.

One of the reasons for my desire to make the acquaintance of Wild Bill was to obtain from his own lips a true account of some of the adventures related to him. It was not an easy matter. It was hard to overcome the reticence which marksmen who have lived the wild mountain life, and which was one of his valuable qualifications as a scout. Finally, he said:

“I hardly know where to begin. Pretty near all these stories are true. I was at it all the war. That affair of my swimming the river took place on that long scout of mine when I was with the rebels five months when I was sent by General Curtis to Price’s army. Things had come pretty close at that time, and it wasn’t safe to go straight inter their lines. Everybody was suspected who came from these parts. So I started off and went way up to Kansas City. I bought a horse there and struck out onto the plains, and then went down through Southern Kansas into Arkansas. I knew a rebel named Barnes, who was killed at Pea Ridge. He was from near Austin in Texas. So I called myself his brother and enlisted in a regiment of mounted rangers.”

“General Price was just then getting ready for a raid into Missouri. It was sometime before we got into the campaign, and it was mighty hard work for me. The men of our regiment were awful. They didn’t mind killing a man no more than a hog. The officers had no command over them. They were afraid of their own men, and let them do what they liked; so they would rob and sometimes murder their own people. It was right hard for me to keep up with them, and not do as they did. I never let on that I was a good shot. I kept that back for big occasions; but ef you’d heard me swear and cuss the blue-bellies, you’d a-thought me one of the wickedest of the whole crew. So it went on until we came near Curtis’s army. Bime-by they were on one side of the Sandy River and we were on t’other. All the time I had been getting information until I knew every regiment and its strength; how much cavalry there was, and how many guns the artillery had. ”

“You see ‘twas time for me to go, but it wasn’t easy to git out, for the river was close picketed on both sides. One day when I was on picket our men and the rebels got talking and cussin each other, as you know they used to do. After a while one of the Union men offered to exchange some coffee for tobacco. So we went out onto a little island which was neutral ground like. The minute I saw the other party, who belonged to the Missouri cavalry, we recognized each other. I was awful afraid they’d let on. So I blurted out:

’Now, Yanks, let’s see yer coffee — no burnt beans, mind yer but the genuine stuff. We know the real article if we is Texans .’”

“The boys kept mum, and we separated. Half an hour afterward General Curtis knew I was with the rebs. But how to git across the river was what stumped me. After that, when I was on picket, I didn’t trouble myself about being shot. I used to fire at our boys, and they’d bang away at me, each of us taking good care to shoot wide. But how to git over the river was the bother. At last, after thinking a heap about it, I came to the conclusion that I always did, that the boldest plan is the best and safest.”

“We had a big sergeant in our company who was alms a-braggin that he could stump any man in the regiment. He swore he had killed more Yanks than any man in the army, and that he could do more daring things than any others. So one day when he was talking loud I took him up and offered to bet horse for horse that I would ride out into the open, and nearer to the Yankees than he. He tried to back out of this, but the men raised a row, calling him a funk, and a bragger, and all that; so he had to go. Well, we mounted our horses, but before we came within shootin’ distance of the Union soldiers I made my horse kick and rear so that they could see who I was. Then we rode slowly to the river bank, side by side.”

“There must have been ten thousand men watching us; for, besides the rebs who wouldn’t have cried about it if we had both been killed, our boys saw something was up, and without being seen thousands of them came down to the river. Their pickets kept firing at the sergeant, but whether or not they were afraid of putting a ball through me I don’t know, but nary a shot hit him. He was a plucky feller all the same, for the bullets zitted about in every direction.”

“Bime-by we got right close ter the river, when one of the Yankee soldiers yelled out, ‘Bully for Wild Bill’”

“Then the sergeant suspicioned me, for he turned on me and growled out, ‘By God, I believe yer a Yank!’ And he at onst drew his revolver; but he was too late, for the minute he drew his pistol I put a ball through him. I mightn’t have killed him if he hadn’t suspicioned me. I had to do it then.”

“As he rolled out of the saddle I took his horse by the bit, and dashed into the water as quick as I could. The minute I shot the sergeant our boys set up a tremendous shout and opened a smashing fire on the rebs who had commenced popping at me. But I had got into deep water, and had slipped off my horse over his back, and steered him for the opposite bank by holding onto his tail with one hand, while I held the bridle rein of the sergeant’s horse in the other hand. It was the hottest bath I ever took. Whew! For about two minutes how the bullets zitted and skipped on the water. I thought I was hit again and again, but the reb sharp-shooters were bothered by the splash we made, and in a little while our boys drove them to cover, and after some tumbling at the bank got into the brush with my two horses without a scratch.”

“It is a fact,” said the scout, while he caressed his long hair,” I felt sort of proud when the boys took me into camp, and General Curtis thanked me before a heap of generals.”

“But I never tried that thing over again, nor I didn’t go a scouting openly in Price’s army after that. They all knew me too well, and you see ‘twouldn’t be healthy to have been caught.”

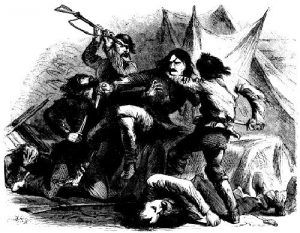

The scout’s story of swimming the river ought, perhaps, to have satisfied my curiosity but I was especially desirous to hear him relate the history of a sanguinary fight which he had with a party of ruffians in the early part of the war, when, single-handed, he fought and killed ten men. I had heard the story as it came from an officer of the regular army who, an hour after the affair, saw Bill and the ten dead men, some killed with bullets, others hacked and slashed to death with a knife.

As I write out the details of this terrible tale from notes which I took as the words fell from the scout’s lips, I am conscious of its extreme improbability; but while I listened to him I remembered the story in the Bible, where we are told that Samson with the jawbone of an ass slew a thousand men, and as I looked upon this magnificent example of human strength and daring, he appeared to me to realize the powers of a Samson and Hercules combined, and I should not have been inclined to place any limit on his achievements. Besides this, one who has lived for four years in the presence of such grand heroism and deeds of prowess as was seen during the war is in what might he called a receptive mood. Be the story true or not, in part, or in whole, I believed then every word Wild Bill uttered, and I believe it today.

“I don’t like to talk about that McCanles affair,” said Bill, in answer to my question.

“It gives me a queer shiver whenever I think of it, and sometimes I dream about it, and wake up in a cold sweat.”

“You see this McCanles was the Captain of a gang of desperadoes, horse thieves, murderers, regular cut-throats, who were the terror of everybody on the border, and who kept us in the mountains in hot water whenever they were around. I knew them all in the mountains where they pretended to be trapping, but they were there hiding from the hangman. McCanles was the biggest scoundrel and bully of them all and was allers a-braggin of what he could do. One day I beat him shootin at a mark, and then threw him at the back-bolt. And I didn’t drop him as soft as you would a baby, you may be sure. Well, he got savage mad about it, and swore he would have his revenge on me some time.”

“This was just before the war broke out, and we were already takin sides in the mountains either for the South or the Union. McCanles and his gang were border-ruffians in the Kansas row, and of course, they went with the rebs. Bime-by he clar’d out, and I shouldn’t have thought of the feller agin ef he hadn’t crossed my path. It ‘pears he didn’t forget me.”

“It was in ‘61 when I guided a detachment of cavalry who were commin from Camp Floyd. We had nearly reached the Kansas line, and were in South Nebraska, when one afternoon I went out of camp to go to the cabin of an old friend of mine, a Mrs. Wellman. I took only one of my revolvers with me, for although the war had broke out I didn’t think it necessary to carry both my pistols, and, in all or’nary scrimmages, one is better than a dozen, if you shoot straight. I saw some wild turkeys on the road as I was goin down, and popped one of ‘em over, thinking he’d he just the thing for supper.”

“Well, I rode up to Mrs. Wellman, jumped off my horse, and went into the cabin, which is like most of the cabins on the prarer, with only one room, and that had two doors, one opening in front and t’other on a yard, like.”

“How are you, Mrs. Wellman?” I said, feeling as jolly as you please.

“The minute she saw me she turned as white is a sheet and screamed: ‘Is that you, Bill? Oh, my God! They will kill you! Run! Run! They will kill you!’”

“Whos a-goin to kill me?” I said. “There’s two can play at that game.”

“’It’s McCanles and his gang. There’s ten of them, and you’ve no chance. They’ve jes gone down the road to the corn-rack. They came up here only five minutes ago. McCanles was draggin poor Parson Shipley on the ground with a lariat round his neck. The preacher was most dead with choking and the horses stamping on him. McCanles knows yer bringin in that party of Yankee cavalry, and he swears he’ll cut yer heart out. Run, Bill, run! But it’s too late; they’re commin up the lane’”

“While she was a-talkin I remembered I had but one revolver, and a load gone out of that. On the table there was a horn of powder and some little bars of lead. I poured some powder into the empty chamber and rammed the lead after it by hammering the barrel on the table, and had just capped the pistol when I heard McCanles shout: ‘There’s that d—d Yank Wild Bill’shorse; he’s here; and we’ll skin him alive!’”

“If I had thought of runnin before, it war too late now, and the house was my best holt –a sort of fortress, like. I never thought I should leave that room alive.”

The scout stopped in his story, rose from his seat, and strode back and forward in a state of great excitement.

“I tell you what it is, Kernel,” he resumed, after a while, “I don’t mind a scrimmage with these fellers round here. Shoot one or two of them and the rest run away. But all of McCanles’ Gang were reckless, blood-thirsty devils, who would fight as long as they had strength to pull a trigger. I have been in tight places, but that’s one of the few times I said my prayers.”

“Surround the house and give him no quarter!’ yelled McCanles. When I heard that I felt as quiet and cool as if I was a-goin to church. I looked round the room and saw a Hawkins rifle hangin over the bed.”

“Is that loaded?” I said to Mrs. Wellman.

“’Yes,’ the poor thing whispered. She was so frightened she couldn’t speak out loud.”

“’Are you sure?’ I said, as I jumped to the bed and caught it from its hooks. Although may eye did not leave the door, yet I could see she nodded Yes again. I put the revolver on the bed, and just then McCanles poked his head inside the doorway, but jumped back when he saw me with the rifle in my hand.”

“’Come in here, you cowardly dog! I shouted. Come in here, and fight me!’

“McCanles was no coward if he was a bully. He jumped inside the room with his gun leveled to shoot, but he was not quick enough. My rifle-ball went through his heart. He fell back outside the house, where he was found afterward holding tight to his rifle, which had fallen over his head.”

“His disappearance was followed by a yell from his gang, and then there was a dead silence. I put down the rifle and took the revolver, and I said to myself: ‘Only six shots and nine men to kill. Save your powder, Bill, for the death-hugs a-comin!’ I don’t know why it was, Kernel,” continued Bill, looking at me inquiringly, “but at that moment things seemed clear and sharp. I could think strong.”

“There was a few seconds of that awful stillness, and then the ruffians came rushing in at both doors. How wild they looked with their red, drunken faces and inflamed eyes, shouting and cussin! But I never aimed more deliberately in my life.”

“One—two—three—four; and four men fell dead.”

“That didn’t stop the rest. Two of them fired their bird guns at me. And then I felt a sting run all over me. The room was full of smoke. Two got in close tome, their eyes glaring out of the clouds. One I knocked down with my fist. “you are out of the way for a while,” I thought. The second I shot dead. The other three clutched me and crowded me onto the bed. I fought hard. I broke with my hand one man’s arm. He had his fingers round my throat. Before I could get to my feet I was struck across the breast with the stock of a rifle, and I felt the blood rushing out of my nose and mouth. Then I got ugly, and I remember that I got hold of a knife, and then it was all cloudy like, and I was wild, and I struck savage blows, following the devils up from one side to the other of the room and into the corners, striking and slashing until I knew that everyone was dead.”

“All of a sudden it seemed as if my heart was on fire. I was bleeding everywhere. I rushed out to the well and drank from the bucket, and then tumbled down in faint.”

Breathless with the intense interest with which I had followed this strange story, all the more thrilling and weird when its hero, seemingly to live over again the bloody events of that day, gave way to its terrible spirit with wild, gestures. I saw then – what my scrutiny of the morning had failed to discover – the tiger which lay concealed beneath that gentle exterior.

“You must have been hurt almost to death,” I said.

“There were eleven buck-shot in me. I carry some of them now. I was cut in thirteen places. All of them bad enough to have let out the life of a man. But that blessed old Dr. Mills pulled me safe through it, after a bed siege of many a long week.”

“That prayer of yours, Bill, may have been more potent for your safety than you think. You should thank God for your deliverance.”

“To tell you the truth, Kernel,” responded the scout with a certain solemnity in his grave face, “I don’t talk about sich things ter the people round here, but I allers fell sort of thankful when I get out of a bad scrape.”

“In all your wild, perilous adventures,” I asked him, “have you ever been afraid? Do you know what the sensation is? I am sure you will not misunderstand the question, for I take it we soldiers comprehend justly that there is no higher courage than that which shows itself when the consciousness of danger is keen but where moral strength overcomes the weakness of the body.”

“I think I know what you mean, Sir, and I’m not ashamed to say that I have been so frightened that it ‘peared as if all the strength and blood had gone out of my body, and my face was as white as chalk. It was at the Wilme Creek fight. I had fired more than fifty cartridges, and I think fetched my man every time. I was on the skirmish line and was working up closer to the rebs when all of a sudden a battery opened fire right in front of me, and it sounded as if forty thousand guns were firing, and ever shot and shell screeched within six inches of my head. It was the first time I was ever under artillery fire, and I was so frightened that I couldn’t move for a minute or so, and when I did go back the boys asked me if I had seen a ghost? They may shoot bullets at me by the dozen, and it’s rather exciting if I can shoot back, but I am always sort of nervous when the big guns go off.”

“I would like to see you shoot.”

“Would yer?” replied the scout, drawing his revolver; and approaching the window, he pointed to a letter O in a signboard which was fixed to the stone wall of a building on the other side of the way.

“That sign is more than fifty yards away. I will put these six balls into the inside of the circle, which isn’t bigger than a man’s heart.”

In an off-hand way, and without sighting the pistol with his eye, he discharged the six shots of his revolver. I afterward saw that all the bullets had entered the circle.

As Bill proceeded to reload his pistol, he said to me with a naiveté of manner which was meant to he assuring:

“Whenever you get into a row be sure and not shoot too quick. Take time. I’ve known many a feller slip up for shootin in a hurry.”

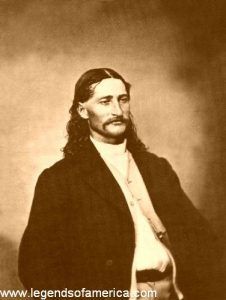

It would be easy to fill a volume with the adventures of that remarkable man. My object here has been to make a slight record of one who is one of the best – perhaps the very best – example of a class who more than any other encountered perils and privations in defense of our nationality.

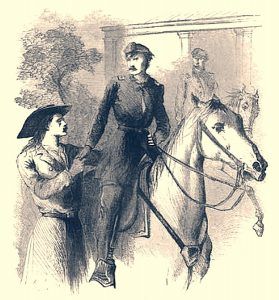

One afternoon as General Smith and I mounted our horses to start upon our journey toward the East, Wild Bill came to shake hands goodby, and I said to him:

“If you have no objection I will write out for publication an account of a few of your adventures.”

“Certainly you may,” he replied. “I’m sort of public property. But., Kernel,” he continued, leaning upon my saddle-bow, while there was a tremulous softness in his voice and a strange moisture in his averted eyes, “I have a mother back there in Illinois who is old and feeble. I haven’t seen her this many a year, and haven’t been a good son to her, yet I love her better than anything in this life. It don’t matter much what they say about me here. But I’m not a cut-throat and vagabond, and I’d like the old woman to know what’ll make her proud. I’d like her to hear that her runaway boy has fought through the war for the Union like a true man.”

William Hickok called Wild Bill, the Scout of the Plains shall have his wish. I have told his story precisely as it was told to me, confirmed in all important points by many witnesses; and I have no doubt of its truth.

— G.W.N.

To see the original article in its entirety, visit the Cornell University Library.

About the Article and the Author:

Hickok bids farewell to George Ward Nichols, illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

This article, written by George Ward Nichols, was excerpted, in part, from an article that appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, entitled Wild Bill, in February 1867, now in the public domain. The article is not verbatim, as glaring errors, such as Nichols referring to Bill Hickok as William Hitchcock, and other grammatical and spelling corrections have been made. Additionally, the material that appears has been truncated.

George Ward Nichols worked as a journalist until the outbreak of the Civil War, when he joined the Union Army, where he served on the staffs of Generals John C. Fremont and William Sherman. Before he was released from service, he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. After the war, he published a number of stories in various publications including the article that appears here.

Newspapers such as the Leavenworth Daily Conservative, Kansas Daily Commonwealth, Springfield Patriot, and the Atchison Daily Champion quickly pointed out that the article was full of inaccuracies and that Hickok was lying when he claimed he had killed “hundreds of men.” After these heavy attacks, he concentrated on writing about music and became president of the Cincinnati College of Music. Books by Nichols include Art Education Applied to Industry in 1877 and Pottery in 1878. He died on September 15, 1885.

Continue next page to criticisms of George Ward Nichols and the Wild Bill Article…