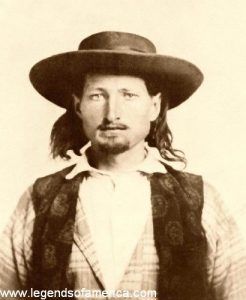

“Dave’s style was right provoking; but Bill answered him perfectly gentlemanly:

‘I think yer wrong, Dave. It’s only twenty-five dollars. I have a memorandum of it in my pocket downstairs. Ef its thirty-five dollars Ill give it yer.’”

“Now Bill’s watch was lying on the table. Dave took up the watch, put it in his pocket,

and said: ‘I’ll keep this yere watch till yer pay me that thirty-five dollars.’”

“This made Bill shooting mad; fur, don’t yer see, Colonel, it was a-doubting his honor like, so he got up and looked Dave in the eyes, and said to him: ‘I don’t want ter make a row in this house. It’s a decent house, and I don’t want ter injure the keeper. You’d better put that watch back on the table.’”

“But Dave grinned at Bill mighty ugly, and walked off with the watch, and kept it several days. All this time Dave’s friends were spurring Bill on ter fight; there was no end ter the talk. They blackguarded him in an underhand sort of a way, and tried ter get up a scrimmage, and then they thought they could lay him out. Yer see Bill has enemies all about, he’s settled the accounts of a heap of men who lived round here. This is about the only place in Missouri whar a reb can come back and live, and ter tell yer the truth, Colonel –” and the Captain, with an involuntary movement, hitched up his revolver-belt, as he said, with expressive significance, “they don’t stay long round here!”

“Well, as I was saying, these rebs don’t like ter see a man walking round town who they knew in the reb army as one of their men, who they now know was on our side, all the time he was sending us information, sometimes from Pap Price’s own headquarters. But they couldn’t provoke Bill inter a row, for he’s afeard of hisself when he gits awful mad; and he allers left his shootin irons in his room when he went out. One day these cusses drew their pistols on him and dared him to fight, and then they told him that Tutt was a-goin ter pack that watch across the squar next day at noon.”

“I heard of this, for everybody was talking about it on the street, and so I went after Bill and found him in his room cleaning and greasing and loading his revolvers.”

“Now, Bill, says I, ‘you’re goin ter git inter a fight.’”

“Don’t you bother yerself Captain,’ says he. ‘It’s not the first time I have been in a fight, and these d—d hounds have put on me long enough. You don’t want me ter give up my honor, do yer?’”

‘No, Bill,’ says I, ‘yer must keep yer honor.’”

“Next day, about noon, Bill went down on the squar. He had said that Dave Tutt shouldn’t pack that watch across the squar unless dead men could walk.”

“When Bill got onter the squar he found a crowd stanin in the corner of the street by which he entered the square, which is from the south yer know. In this crowd he saw a lot of Tutt’s friends; some were cousins of his’n, just back from the reb army; and they jeered him, and boasted that Dave was a-goin to pack that watch across the squar as he promised.”

“Then Bill saw Tutt stanin near the courthouse, which yer remember is on the west side, so that the crowd war behind Bill.”

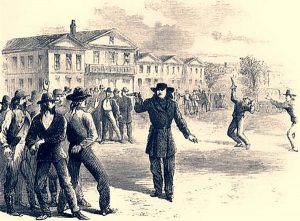

“Just then Tutt, who was alone, started from the courthouse and walked out into the square, and Bill moved away from the crowd toward the west side of the squar. Bout fifteen paces brought them opposite to each other, and bout fifty yards apart. Tutt then showed his pistol. Bill had kept a sharp eye on him, and before Tutt could pint it Bill had his’n out.”

After the Springfield, Missouri shoot-out, Hickok turned on Tutt’s friends, illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February, 1867.

“At that moment you could have heard a pin drop in that square. Both Tutt and Bill fired, but one discharge followed the other so quick that it’s hard to say which went off first. Tutt was a famous shot, but he missed this time; the ball from his pistol went over Bill’s head. The instant Bill fired, without waitin ter see ef he had hit Tutt, he wheeled on his heels and pointed his pistol at Tutt’s friends, who had already drawn their weapons.

“‘Aren’t yer satisfied, gentlemen?’ cried Bill, as cool as an alligator. ‘Put up your shootin-irons, or there’ll be more dead men here. And they put ‘em up, and said it war a far fight.”

“What became of Tutt?” I asked of the Captain, who had stopped at this point of his story, and was very deliberately engaged in refilling his empty glass.”

“Oh! Dave? He was as plucky a feller as ever drew trigger; but, Lord bless yer! it was no use. Bill never shoots twice at the same man, and his ball went through Dave’s heart. He stood stock-still for a second or two, then raised his arm as if ter fire again, then he swayed a little, staggered three or four steps, and then fell dead.”

“Bill and his friends wanted ter have the thing done regular, so we went up ter the Justice, and Bill delivered himself up. A jury was drawn; Bill was tried and cleared the next day. It was proved that it was a case of self-defense. Don’t yer see, Colonel?”

I answered that I was afraid that I did not see that point very clearly.

“Well, well!” he replied, with an air of compassion, you haven’t drunk any whisky, that’s what’s the matter with yer.” And then, putting his hand on my shoulder with a half-mysterious half-conscious look in his face, he muttered, in a whisper:

“The fact is, thar was an undercurrent of a woman in that fight!”

The story of the duel was yet fresh from the lips of the Captain when its hero appeared in the manner already described. After a few moments conversation, Bill excused himself, saying:

“I am going out on the prarer a piece to see the sick wife of my mate. I should be glad to meet yer at the hotel this afternoon, Kernel.”

“I will go there to meet you,” I replied.

“Good-day, gentlemen,” said the scout, as he saluted the party, and mounting the black horse who had been standing quiet, unhitched, he waved his hand over the animal’s head. Responsive to the signal, she shot forward as the arrow leaves the bow, and they both disappeared up the road in a cloud of dust.

I went to the hotel during the afternoon to keep the scout’s appointment. The large room of the hotel in Springfield is perhaps the central point of attraction in the city. It fronted on the street and served in several capacities. It was a sort of exchange for those who had nothing better to do than to go there. It was reception-room, parlor, and office; but its distinguished and most fascinating characteristic was the bar, which occupied one entire end of the apartment. Technically, the “bar” is the counter upon which the polite official places his viands. Practically, the bar is represented in the long rows of bottles, and cut-glass decanters, and the glasses and goblets of all shapes and sizes suited to the various liquors to be imbibed. What a charming and artistic display it was of elongated transparent vessels containing every known drinkable fluid, from native Bourbon to imported Lacryma Christi!

The room, in its way, was a temple of art. All sorts of pictures budded and blossomed and blushed from the walls. Sixpenny portraits of the Presidents encoffined in pine-wood frames; Mazeppa appeared in the four phases of his celebrated one-horse act; while a lithograph of “Mary Ann” smiled and simpered in spite of the stains of tobacco-juice which had been unsparingly bestowed upon her countenance. But the hanging committee of this un-designed academy seemed to have been prejudiced as all hanging committees of good taste might well be — in favor of Harper’s Weekly; for the walls of the room were well covered with wood cuts cut from that journal. Portraits of noted generals and statesmen, knaves and politicians, with bounteous illustrations of battles and skirmishes, from Bull Run number one to Dinwiddie Court House. And the simple-hearted comers and goers of Springfield looked upon, wondered, and admired these pictorial descriptions fully as much as if they had been the masterpieces of a Yvon or Vernet.

A billiard table, old and out of use, where caroms seemed to have been made quite as often with lead as ivory balls, stood in the center of the room. A dozen chairs filled up the complement of the furniture. The appearance of the party of men assembled there, who sat with their slovenly shod feet dangling over the arms of the chairs or hung about the porch outside, was in perfect harmony with the time and place.

All of them religiously obeyed the two before-mentioned, characteristics of the people of the city — their hair was long and tangled, and each man fulfilled the most exalted requirement of laziness.

I was taking a mental inventory of all this when a cry and murmur drew my attention to the outside of the house when I saw Wild Bill riding up the street at a swift gallop. Arrived opposite to the hotel, he swung his right arm around with a circular motion. Black Nell instantly stopped and dropped to the ground as if a cannonball had knocked the life out of her. Bill left her there, stretched upon the ground, and joined the group of observers on the porch.

“Black Nell hasn’t forgotten her old tricks,” said one of them.

“No,” answered the scout. “God bless her! She is wiser and truer than most men I know of. That mare will do any thing for me. Won’t you, Nelly?” The mare winked affirmatively the only eye we could see.

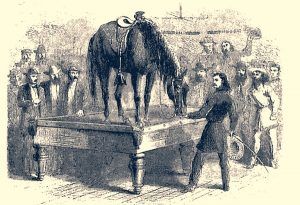

Black Nell, Bill Hickok’s horse, climbs on a billiard table at Hickok’s command, illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

“Wise!” continued her master; “why, she knows more than a judge. I’ll bet the drinks for the party that sh’ell walk up these steps and into the room and climb up on the billiard table and lie down.”

The bet was taken at once, not because anyone doubted the capabilities of the mare, but there was excitement in the thing without exercise.

Bill whistled in a low tone. Nell instantly scrambled to her feet, walked toward him, put her nose affectionately under his arm, followed him into the room, and to my extreme wonderment climbed upon the billiard-table, to the extreme astonishment of the table no doubt, for it groaned under the weight of the four-legged animal and several of those who were simply bifurcated, and whom Nell permitted to sit upon her. When she got down from the table, which was as graceful performance as might be expected under the circumstances, Bill sprang upon her back, dashed through the high wide doorway, and at a single bound cleared the flight of steps and landed in the middle of the street.

The scout then dismounted, snapped his riding-whip, and the noble beast bounded off down the street, rearing and plunging to her own intense satisfaction. A kindly-disposed individual, who must have been a stranger, supposing the mare was running away, tried to catch her when she stopped, and as if she resented his impertinence, let fly her heels at him and then quietly trotted to her stable.

“Black Nell has carried me along through many a tight place,” said the scout, as we walked toward my quarters. “She trains easier than any animal I ever saw. That trick of dropping quick which you saw has saved my life and again. When I have been out scouting on the prairie or in the woods I have come across parties of rebels, and have dropped out of sight in the tall grass before they saw us. One day a gang of rebs who had been hunting for me, and thought they had my track, halted for half an hour within fifty yards of us. Nell laid as close as a rabbit and didn’t even whisk her tail to keep the flies off; until the rebs moved off, supposing they were on the wrong scent. The mare will come at my whistle and foller me about just like a dog. She won’t mind anyone else, nor allow them to mount her, and will kick a harness and wagon all ter pieces ef you try to hitch her in one. And she’s right, Kernel,” added Bill, with the enthusiasm of a true lover of a horse sparkling in his eyes. “A hoss is too noble a beast to be degraded by such toggery. Harness mules and oxen, but give a hoss a chance ter run.”

I had a curiosity, which was not an idle one to hear what this man had to say about his duel with Tutt, and I asked him:

“Do you not regret killing Tutt? You surely do not like to kill men?”

“As ter killing men,” he replied, “I never thought much about it. Most of the men I have killed it was one or the other of us, and at sich times you don’t stop to think; and what’s the use after it’s all over? As for Tutt, I had rather not have killed him, for I want ter settle down quiet here now. But thar’s been hard feeling between us a long while. I wanted ter keep out of that fight; hut he tried to degrade me, and I couldn’t stand that, you know, for I am a fighting man, you know.”