By the end of the 15th century, the Middle Ages came close as the modern world emerged. The legacy of the Middle Ages — the “Age of Faith,” during which Rome fell, and the church gained power, left its mark on the future of religion in Europe. In 1492, Spain militarily defeated the Moors (Muslim inhabitants) and initiated a period of expulsion for those who would not convert to Christianity.

Following Christopher Columbus‘ first voyage in 1492, Spain had a new goal in that regard. In 1493, Spanish Queen Isabella I proclaimed the New World to be a part of the Spanish Empire and ordered that its native peoples were to be treated humanely and converted to Christianity. Thus began the history of the missions that would become a part of our national story and influence our shared common history with Spain, Mexico, and Latin America across time.

Throughout the colonial period, the missions Spain established would serve several objectives. The first would be to convert natives to Christianity. The second would be to pacify the areas for colonial purposes. A third objective was to acculturate the natives to Spanish cultural norms to move from mission status to parish status as full members of the congregation. Mission status made participating natives wards of the State instead of citizens of the empire. Aside from spiritual conquest through religious conversion, Spain hoped to pacify areas that held extractable natural resources such as iron, tin, copper, salt, silver, gold, hardwoods, tar, and other such resources, which investors could then exploit. The missionaries hoped to create a utopian society in the wilderness.

To assure that the missionaries would sustain themselves, Spain established the Patronato Real de las Indias (Royal Patronage of the Indies), which supported the Spanish Crown’s absolute control over ecclesiastical matters within the empire. The Spanish king and his council approved missionaries to go to the Americas, directed the geographic location of missions, and allocated funds for each projected enterprise. Under the Patronato Real, which also governed appointments of Church officials to high office, some viceroys in Mexico and Peru were also archbishops, further cementing the Church-State alliance in a common cause. The missions served as the Church and State agencies to spread the faith to natives and appease them for the State’s aims. By intermingling religion, politics, and economics, the Patronato Real formed a significant archival record of exploration, settlement, missionary activity, ethnographic data, and extraction of raw resources.

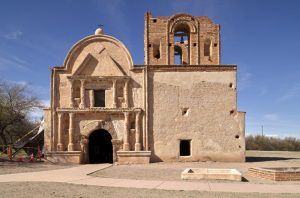

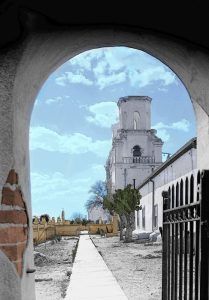

By definition, the “mission” was nothing more than a plan of conversion. Missionaries, usually working alone or with a small military escort, would approach a group of natives and began preaching through a translator with a portable altar to say the Mass. The construction of a church, a garden, classrooms, housing for priests and converts, a refectory, corrals, and a defensive wall with a gate came later. Architecturally, the structures lent themselves to a variety of purposes that a completed mission site would serve. The mission complex served as a religious center as well as a vocational center. The mission was also an economic center for trade and crop production, which non-contiguous lands for ranching and farming supported. Lastly, the mission was a defensive center with heavy gates and doors and shuttered windows on high walls and clerestories. A modern-day misconception is that the church was the mission.

In North America, early missionary efforts commenced in Florida after 1565 and along the eastern coastline to the Chesapeake Bay by the early 1570s, New Mexico after 1598, Texas in the late 1690s, Arizona in the 1680s, and in California in the 1770s. Far from Spanish settlements, lone missionaries lived and worked at great peril among mostly hostile natives. Generally avoiding the Great Plains and mountain tribes with strong warrior societies, missionaries focused on sedentary farming tribes, such as the Pueblos of New Mexico and semi-sedentary tribes along the riverways in Texas and Arizona.

In most cases, Spanish arms were necessary for the mission program to succeed, especially in northern New Spain, today’s Greater Southwest, and northern Mexico. Where possible, presidios were constructed near settlements and missions. In 1772, Friar Romualdo Cartagena, guardian of the College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro, one of the training centers for missionaries, wrote:

“What gives the missions their permanency is the aid which they receive from the Catholic arms. Without them, pueblos are frequently abandoned, and ministers are murdered… It is seen every day that in missions where there are no soldiers, there is no success… Soldiers are necessary to defend the Indian from the enemy, and to keep an eye on the mission Indians, now to encourage them, now to carry the news to the nearest presidio in case of trouble. For the spiritual and temporal progress of the missions, two soldiers are needed…especially in new conversions.”

Theoretically, the missions were designed for ten years, after which the missionaries were expected to move on to newly established areas. However, the scheduled plan of conversion did not work well due to Indian resistance to the rigors of the missions. In the long run, arguing that the natives were imperfectly converted because they reverted to their spiritual ways in secret, friars proposed extending missions another decade. Often such extensions lasted for several decades, if not a century, longer than intended.

By the end of the 18th century, and especially after the Latin America’s Independence Movement from Spain, newly established revolutionary governments removed mission lands from Church authority. In most cases, emerging nations granted citizenship to native groups, kept them as wards of the state, or treated them as social outcasts.

Spanish colonial missions in North America are significant because so many were established and had lasting effects on the cultural landscape. Like forts and towns, the Spanish missions were frontier institutions that pioneered European colonial claims and sovereignty in North America.

Much has been written about the missions and their legacy, ranging from the diffusion of Spanish culture, religion, governance, and language to dialogues condemning their role in altering native cultural practices, customs, and spiritual beliefs. Undoubtedly, a cultural fusion resulted from European and native contact, and many tribes that participated in the evolving mission process still practice Catholicism. While colonists intended to convert, civilize and exploit native groups, the natives had notions about being exploited or having their cultural and spiritual domains threatened by colonial policies imposed on them. Their view, far from the utopian dreams of the missionaries, was often expressed as an unequivocal rejection of the mission process. Native American resentment toward the missions and overall colonial policies often resulted in a series of rebellions that sometimes took years, if not decades, to resolve. Over time, the missions made their mark on American Indian tribes, and Indian spiritual customs, in part, melded with Christianity.

Today, many of these historic Spanish missions are windows to our national past.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Missions & Presidios in the United States

San Antonio Missions National Historic Park

About the Article: The base document of this article was written by Joseph P. Sánchez, Ph.D. and featured by the National Park Service. However, as it appears here, it has been truncated, edited, and additional information included.