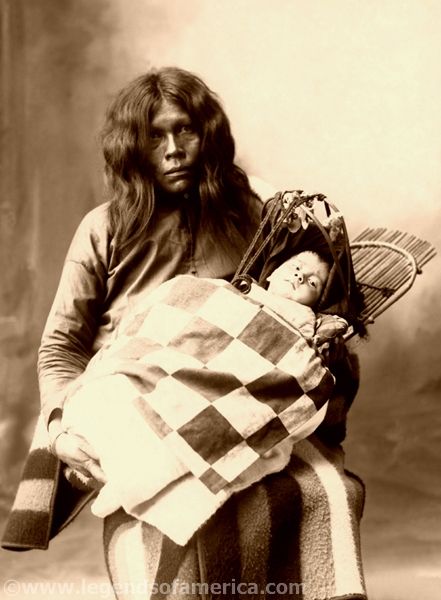

Wichita warrior, 1927, by Edward S. Curtis

by Frederick Webb Hodge, 1906

Of Caddoan stock, the Wichita Indians formerly ranged from about the middle Arkansas River, Kansas, southward to the Brazos River, Texas. They called themselves Kitikiti’sh (Kirikirish), which is of uncertain meaning, but probably implies preeminent men. By the Sioux, they were known as the “Black Pawnee,” to French traders, “Tattooed Pawnee,” and to the Kiowa and Comanche by names meaning “Tattooed Faces.” Other tribes composed the Wichita Confederacy, each of which probably spoke a slightly different dialect of the common language. These included Tawehash, Tawakoni, Waco, Yscani, Akwesh, Asidahetsh, Kishkat, and Korishkitsu. Their language was closely related to the Pawnee, with whom they appeared to have always been on good terms.

Like all tribes of Caddoan lineage, the Wichita were primarily sedentary and agricultural, but owing to their proximity to the buffalo plains, they also hunted to a considerable extent.

Their permanent communal habitations were of conical shape, of diameter from 30 to 50 feet, and consisted of a framework of stout poles overlaid with grass thatch, which had the appearance of a haystack.

Around the inside were ranged the beds upon elevated platforms, while the fire hole was sunk in the center. The doorways faced east and west, and the smoke hole was on one side of the roof a short distance below the apex. There were also drying platforms and arbors thatched with grass similarly. The skin tipi was used when away from home. The Wichita raised large quantities of corn and traded the surplus to the neighboring hunting tribes. They also raised pumpkins and tobacco. Their corn was ground upon stone metates or in wooden mortars. Their women made pottery to a limited degree. In their original condition, both sexes went nearly naked, the men wearing only a breechcloth and the women a short skirt. Still, from their abundant tattooing, they were designated preeminently as the “tattooed people” in the sign language. Men and women generally wore their hair flowing loosely. They buried their dead in the ground, erecting a small framework over the mound.

The Wichita did not have a clan system. They were highly given to ceremonial dances, particularly the picturesque “Horn dance,” nearly equivalent to the Green Corn dance of the Eastern tribes. They also had ceremonial races in which the whole tribe joined. Later, they took up the Ghost Dance and Peyote rite. In general character, the Wichita were described as industrious, reliable, and of friendly disposition.

They first met European explorers in 1541, when the Spanish explorer Francisco Vazquez de Coronado entered the territory known to his New Mexican Indian guides as the country of Quivira. At this time, they were encamped about the great bend of the Arkansas River and northeastward in central Kansas. Coronado and his men stayed in the area for about a month before departing. However, they left behind Franciscan Father Juan de Padilla, with several companions, to undertake the Christianization of the tribe, the earliest missionary work ever undertaken among the Plains Indians. However, after more than three years with the Wichita, they killed Padilla through jealousy of his spiritual efforts for another tribe.

Skidi and Wichita dancers, Edward S. Curtis, 1927. Touch of color by LOA.

In 1719 the French commander La Harpe visited a large camp of the confederated Wichita tribes on the South Canadian River in the eastern Chickasaw Nation, Oklahoma, and was well received by them. He estimated the gathering, including other Indians present, at 6,000. They had been at war with another tribe and had taken several prisoners they were preparing to eat, having already disposed of several in this way.

The Wichita were gradually forced westward and southward by the inroads of the Osage and the Chickasaw Indians to locations on the upper Red and Brazos Rivers, where they were first known to American settlers. In 1758, the Spanish mission and Presidio of San Sabá, on a tributary of the upper Colorado River, Texas, were attacked. A combined force of Comanche, Tawakoni, Tawehash, Kichai, and others destroyed the mission.

In the following year, the Spanish commander, Ortiz Parilla, undertook a retaliatory expedition against the main Wichita camp at the junction of Wichita and Red Rivers but was compelled to retreat in disorder, with the loss of his train and field guns, by a superior force of well-fortified Indians, armed with guns and lances and flying the French flag.

In 1760 the confederated Wichita tribes asked for peace and the establishment of a mission. When they were refused the mission, they renewed their attacks in the San Antonio, Texas, area. In 1765 they captured and held a Spaniard named Tremiño, who left a valuable record of his experiences at the main Tawehash town on the Red River.

In 1772 the commander, Athanase de Mezières, visited them and other neighboring tribes to arrange peace. From his descriptions, the Tawakoni, in two camps on the Brazos and Trinity Rivers, may have had 220 warriors, the Waco 60, and the Wichita and Taovayas 600, a total of perhaps 3,500, not including the Kichai. In 1777-78 an epidemic, probably smallpox, swept the whole of Texas, including the Wichita Indians, reducing some tribes by one-half. The Wichita, however, suffered but little on this occasion. In the spring of 1778, Mezières again visited them. They found the Tawakoni and Waco in two camps on the Brazos River with more than 300 men and the leading tribe of the Wichita in two other camps on opposite sides of the Red River, in which he estimated more than 800 men and as many as 3,200 people in total. The whole body probably exceeded 4,000.

In 1801, the Texas tribes were again ravaged by smallpox; this time, the Wichita suffered heavily. In 1805, the Wichita and their bands were estimated to have been reduced to about 2,600 people.

An estimate in 1824 recorded them at about 2,800, primarily living at the present-day site of Waco, Texas, and on the east side of the Brazos River above the San Antonio Road. Afterward, with the advent of the Austin colony, until the annexation of Texas by the United States, a period of about 25 years, their numbers constantly diminished in conflicts with the American settlers and the raiding Osage from the north.

In 1835 the primary Wichita band, together with the Comanche, made their first treaty with the Government, by which they agreed to live in peace with the United States and with the Osage and the immigrant tribes lately removed to Indian Territory. In 1837 a similar treaty was negotiated with the Tawakoni, Kiowa, and Kiowa Apache. At this time, the Wichita had their main village behind the Wichita Mountains, on the North Fork of Red River in Oklahoma. Later, they moved farther east and settled on the present site of Fort Sill, Oklahoma. In 1850, they moved still farther east to Rush Springs. In the meantime, the Tawakoni and Waco were ranging about the Brazos and Trinity Rivers in Texas.

In 1846, after the annexation of Texas, a general treaty of peace was made at Council Springs on the Brazos River with the main Wichita tribe, the Tawakoni, and Waco, together with the Comanche, Lipan, Caddo, and Kichai, by which all these acknowledged the jurisdiction of the United States. In 1855 the majority of the Tawakoni and Waco, together with a part of the Caddo and Tonkawa, were gathered on a reservation on the Brazos River west of present-day Weatherford, Texas. However, due to the determined hostility of the Texans, the reservation was abandoned in 1859, and the Indians were removed to a temporary location on the Washita River in Oklahoma. Before the removal, the Tawakoni and Waco were officially reported to numbers 204 and 171, respectively. In the meantime, the Wichita had fled from the village at Rush Springs and taken refuge at Fort Arbuckle to escape the vengeance of the Comanche, who held them responsible for a recent attack upon themselves by United States troops under Major Van Dorn in 1858.

The Civil War brought about additional demoralization and suffering, with most of the refugee Texas tribes, including the Wichita, taking refuge in Kansas until it was over. They returned in 1867, having lost heavily by disease and hardship, and were finally assigned a reservation on the north side of Washita River within what is now Caddo County, Oklahoma. The following year they were officially reported at 572, besides 123 Kichai. In 1902 they were given allotments in severalty, and the reservation was thrown open to settlement.

Wee-tá-ra-shá-ro, Head Chief of the Wichita Tribe, 1834, painting by George Caitlin, now held at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

By 1906, the Wichita tribe numbered only about 310, besides about 30 of the confederated Kichai remnant, less than one-tenth of their original number.

Today, the tribe is officially recognized as the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, which includes the Wichita, Keechi, Waco, and Tawakoni Indians. Located in Anadarko, Oklahoma, the tribe numbers about 2,400 members.

Wichita and Affiliated Tribes

P.O. Box 729

1 ¼ Miles North On Hwy 281

Anadarko, Oklahoma 73005

Frederick Webb Hodge, 1906. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

About the Article: Most of this historic text was published in the Handbook of American Indians, written by Frederick Webb Hodge and published in 1906. Hodge (1864-1956) was an editor, anthropologist, archaeologist, and historian who published more than 350 items, including books, monographs, and articles in scientific and historical journals. In addition to his research, excavation, and writing activities, he was employed by the Smithsonian Institution, the Bureau of American Ethnology, and the Museum of the American Indian in New York City, as well as serving as a member and officer of several organizations. Though the essence of his article is essentially intact, the text that appears on this page is far from verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing have occurred for clarity and ease for the modern reader.

Also See: