Mission San Gregorio de Abo, located in central New Mexico, is a pueblo ruin and historic Spanish mission that dates back to the early 1600s. Today, the National Historic Landmark is part of the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument.

The Salinas Valley is home to a rich and complex heritage, interwoven with ancient Pueblo culture and early Spanish colonization. This valley is believed to have been occupied as early as the 10th century by the Mogollon and, later, Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi). It was an important location for trade between the tribes of the Rio Grande and those on the Western Plains. Pueblo ruins at Abó date to around 1300, a time of great prosperity and cultural growth for the valley people. Mogollon and Ancestral Puebloan traditions blended to form the Tompiro culture. The Tompiro were skilled as craftspeople, hunters, and builders and in their agricultural practices. At its height, Abó Pueblo must have been an impressive, bustling community.

The Spanish first arrived in New Mexico in 1540 when explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado led an expedition in search of the rumored seven cities of gold. He found, instead, intricate pueblo communities and the talented, economically sophisticated people who occupied them. This initial expedition inspired further forays into the area. In 1598, Juan de Oñate encountered the Salinas Valley and the large Pueblo societies at Abó, Quarai, and Gran Quivira. By this time, the area’s people had evolved into one of the most advanced and economically powerful cultures in the American Southwest.

The Pueblo Indians, who had perfected their craft-making and agricultural and hunting techniques, commanded the Indian trade paths with their abundance of goods. Because of their superior architectural skills, their impressive stone-and-adobe homes dominated the southwestern landscape. The Spanish found the Pueblo pottery, farming, and building techniques impressive, and recognizing the value of the American Indians’ skilled labor; the Spanish established a permanent settlement.

The Spanish quickly implemented the encomienda system, which demanded tribute and forced labor from the Indian inhabitants of the area. The Spanish governor then appointed ranking Spanish citizens to protect, educate, and civilize the Indians. In return, the Spanish collected tribute in the form of labor, food, and material goods. Eventually, the Spanish began abusing the system, and tensions grew. Though the Franciscan friars attempted to help the Pueblo peoples, the church was powerless against the government, and the lucrative system continued.

Conflict also grew from the religious pressure that Franciscan friars placed on the American Indians. The clash of religions made it difficult for the missionaries to convert Pueblo peoples unwilling to give up sacred customs, which the Indians believed brought good fortune to their communities. The Franciscans attempted to stop the Pueblo people from performing these customs by informing the Indians that their people’s salvation depended on their conversion to Christianity.

Spanish missionaries worked to bring Catholicism to the approximately 1,500 natives living at Abó Pueblo. Fray Francisco Fonte established Mission San Gregorio de Abó around 1621, and by 1629, the large San Gregorio de Abó Church was completed. Built of red sandstone, the church used a European-style buttress system that allowed the building to have notably tall, thin walls. The church formed the center of mission activity for the next 50 years. In 1641, the pueblo was called home to a population of more than 1,600.

Franciscan missionaries brought new religious ideas to the area and introduced the people of Abó to new species of domestic animals and plants, different agricultural practices, and Spanish goods. Archeological and historical research at the site uncovered evidence of corrals and stables for livestock, like sheep and goats the mission kept. People used salt, ate a combination of native foods like corn, pumpkin, prickly pear, cholla, juniper, piñon nuts, yucca, amaranth, and turkey eggs, as well as European introduced foods like grapes, plums, and peaches. Also found at the site, Chinese porcelains imported from the Philippines and Mexican Majolica and olive jar style ceramics brought north from Mexico materially connect Abó to the rest of the Spanish empire.

While the Franciscans likely had good intentions for the people of Abó, eventually, the clash of cultures led to the failure of the San Gregorio de Abó Mission. Many Tompiro people refused to give up their sacred customs for new Catholic beliefs, especially when a series of droughts, epidemics, and Apache attacks hit the Pueblo starting in the mid-1600s, providing proof to many that Catholicism insulted their Tompiro gods.

By 1672, the Abó Pueblo and its mission had only about 500 residents remaining of what had been a much larger thriving community. Native inhabitants who abandoned Abó are believed to have joined their Piro-speaking relatives along the Rio Grande. In 1678, the pueblo was entirely unoccupied.

For over 100 years, Abó was quiet. In 1815, Spanish sheepherders attempted to return to the area, but the Apache Indians pushed them out in 1830. Settlers permanently returned in 1865.

Major excavation and stabilization occurred when the site became a New Mexico State Historic Monument in the 1930s. In 1962, Abó was designated a National Historic Landmark, and in 1980, the ruins became part of the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument. The Mission San Gregorio de Abó Church is the only extant example of a thin-walled, buttressed, 17th century New Mexican church. It is also one of the earliest Spanish ruins in the Southwest. Roughly 40 percent of the original Pueblo buildings remain as ruins, and many have never been excavated, even though they likely contain important archeological information about the ancient peoples of the valley.

A visit to the Abó site reveals the intersections between the American Indian and Spanish cultures in the 17th century that has shaped modern New Mexico.

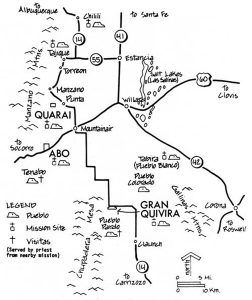

Access to the site of the ruins and the pueblo is through the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, which offers interpreted tours and self-guided walks through the ruins of Abó, Quarai, and Gran Quivira pueblos and their associated Spanish missions: La Purisma Conception de Cuarac, San Buenaventura, and San Isidro. Recent stabilization efforts have made it possible for visitors to walk directly around and within the old walls of the Abó mission church and explore the largely unexcavated Pueblo structures.

The Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument is located 10 miles west of Mountainair, New Mexico, off Route 60. The main visitor center for Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument is located on the corner of Ripley and Broadway Streets in Mountainair. Admission is free at all times.

More Information:

Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument

PO Box 517

Mountainair, New Mexico 87036-0517

505-847-2585

Compiled & edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2021.

Also See:

Missions & Presidios of the United States

Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument

Source – National Park Service