The Colfax County War, taking place in northeast New Mexico, was a vicious dispute over property ownership from 1873 to 1888. The disputed land was once part of the largest land grant ever made in the United States — The Maxwell Land Grant.

The land, which included large portions of Colfax County, New Mexico, and Las Animas County, Colorado, was initially granted to Charles H. Beaubien and Guadalupe Miranda in 1841 by the Spanish Government. After Lucien Maxwell married Beaubien’s daughter and became a part-owner and manager of the vast land grant, he bought out the other owners over time.

Two times larger than the State of Rhode Island, the area included the towns of Cimarron, Springer, Raton, Elizabethtown in New Mexico, and Segundo and other towns in Colorado. The area is surrounded by breathtaking mountain views, beckoning valleys, streams teeming with fish, and hillsides alive with game. During Maxwell’s ownership, the area was thriving, with people coming and going along the Santa Fe Trail, developing settlements, and mining for gold.

After developing much of the property and operating several businesses on the land, Lucien Maxwell sold the property to Senator Chafee of Colorado and two others for $650,000 in 1870. He then sold all of his other assets on the property for an additional $100,000 and moved to Fort Sumner, New Mexico.

Senator Chaffee and the others who had purchased the land from Maxwell almost immediately sold it to an English syndicate for $1,350,000, and, just six months later, it was sold again to a Dutch Firm in 1872. The new grant owners immediately began to aggressively exploit the resources of the grant, opening a sales office at Maxwell’s old place in Cimarron. They waited for the customers to rush in, and they continued to wait. Faltering gold production and the shadow of Indian attacks spooked potential buyers. Meanwhile, folks who had already settled on the grant were riled at the quick way the new owners tried to collect rents, despite the Dutch company’s legal right to the property.

An old building in the Moreno Valley of New Mexico was part of the Maxwell Land Grant by Kathy Alexander.

One of the first items on the Grant owners’ agenda was the removal of the squatters who had moved on the grant during the past 30 years. The farmers and miners who had settled on the grant had held a grudging respect for Lucien Maxwell, but they felt no such loyalty to the absentee foreign firm. Having invested their lives and money into homes and businesses, the settlers were not prepared to leave, primarily because of the contested title Maxwell had conveyed.

To remove the settlers from their property, grant officials, in league with a group of lawyers, politicians, and businessmen known as the Santa Fe Ring, began making false allegations against locals. Two Cimarron citizens were known to have supported the “Ring” — Melvin Mills, an attorney, and Robert H. Longwell, Cimarron’s local doctor. In 1875 local elections were held with much controversy, and Dr. Longwell was made probate judge, while attorney Mills was made a state Legislator.

The Santa Fe Ring’s two prime movers were attorney Thomas Benton Catron and his law partner, Steven Benton Elkins, later a Senator. Fellow “Ring” members were chosen for whatever talent they could contribute or political or financial influence they could provide.

Cimarron had already obtained a reputation for lawlessness, and as the hired gunslingers of the Land Grant company tried to force off the squatters, it quickly led to what became known as the Colfax County War. Unfortunately for the settlers, they were outnumbered and outgunned from the start.

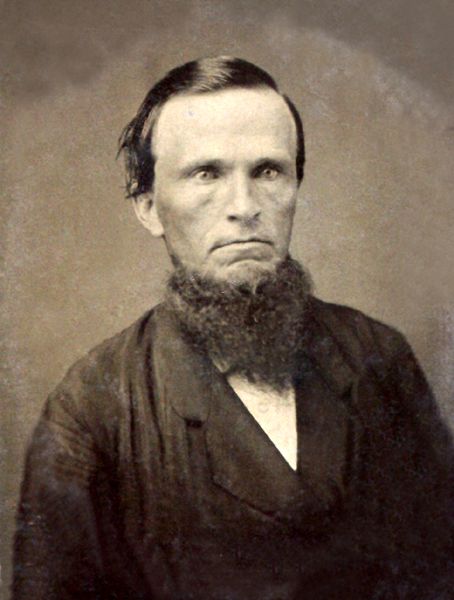

Reverend Franklin J. Tolby, one of two Methodist ministers holding services in the area, quickly sided with the settlers against the land grant men. The 33-year-old Tolby was a vociferous critic of the Santa Fe Ring and sent a series of letters to the New York Sun exposing the group’s corrupt methods, as well as making public statements at every opportunity that he would do whatever he could to break up the grant.

On September 14, 1875, the minister was shot in Cimarron Canyon, midway between Elizabethtown and Cimarron, near Clear Creek. It was clear that robbery had not been the motive because the preacher’s horse, saddle, and personal belongings were untouched. It was quickly assumed that someone from the Land Grant company had taken revenge against Tolby’s opinions and quieted him forever. Five days after his body was found, the Daily New Mexican of Santa Fe reported: “It is thought the murderer is a white man and paid for the job.”

However, if the murderer thought that killing Reverend Tolby would quiet the opposition to the land grant, they couldn’t have been more wrong. The settlers immediately blamed the Grant men and the politicians who were said to have been “in their pockets.” If anything, the murder further inflamed the citizens and led to more concerted efforts to challenge the approval of the grant. The Colfax County Ring, as the settlers called themselves, rode like avenging angels cutting down the just and unjust alike.

Tolby’s 34-year old minister friend, Reverend Oscar Patrick McMains, took up the holy war, urging in a public speech, “Defiance! And Contempt for that which is Contemptible.” Further, he wrote, “The war is on; the precious blood of settlers has been shed, and we must fight it out on this line. No quarter now for the foreign land thieves and their hired assassins…”

Despite a $3,000 reward for the murderer, no progress was made in finding Tolby’s killer, and McMains became impatient. Rumors circulated that the new Cimarron Constable, Cruz Vega, was somehow involved in Tolby’s murder.

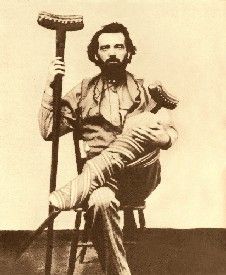

The pastor turned to Clay Allison, a local gunslinger, for help. On the evening of October 30, 1875, a masked mob, who was said to have been led by Clay Allison and Minister McMains, confronted Vega. The constable denied having anything to do with the murder, blaming it on a man named Manuel Cardenas. The mob did not believe him, and he was pummeled and hanged by the neck from a telegraph pole. Unable to stomach the violence, the Reverend McMains had panicked and fled midway through the session.

Manuel Cardenas, the man Vega had implicated before his death, was arrested and questioned in Elizabethtown ten days later. He claimed that Vega had shot the minister, adding that Santa Fe Ringers Mills and Longwell were also behind the killing.

Mills barely escaped a furious lynch crowd in Cimarron as he descended from a coach and was later arrested. Longwell fled in a buggy to Fort Union and safety just ahead of pursuers Clay and John Allison.

Mills was granted a trial, but during the trial, the state governor was informed of the events by telegraph, and the cavalry was dispatched from Fort Union, arriving just in time to end the proceedings and release Mills.

During his protracted hearing, Cardenas retracted his earlier accusations against Mills and Longwell, thus clearing the two men. Furthermore, he stated that in Elizabethtown, he had been coerced at gunpoint into implicating the two when he was “questioned” at gunpoint by Joseph Herberger. Herberger had been promised a political position by Ring men Mills and Longwell during the earlier elections in 1875.

When the two had failed to follow through, Herberger reportedly forced Cardenas to implicate them. While Cardenas was escorted back to the jail when court adjourned one evening, he was shot to death. It was never known who killed Cardenas, though many thought it was the vigilantes fighting against the Santa Fe Ring, led by Clay Allison.

The truth about Tolby’s murder later suggested that the parson, unfortunately, witnessed a man named Francisco Griego shooting a man in an argument. When the man later died, Tolby planned to seek an indictment against Griego, who set up Tolby’s murder to silence him. Cardenas later retracted his statement about the Ring men. To this day, the murders of Tolby, Vega, and Cardenas are officially unsolved.

The reign of terror had begun in Cimarron, and the town was out of control. Violence, lawlessness, and apprehension fed the residents, and many packed their belongings and left the area.

At one time, guards were posted at all entrances to Cimarron, and no one was allowed to leave town without the Colfax County Ring’s permission. By November 9, 1875, the Santa Fe New Mexican informed the public that Cimarron was in the hands of a mob. The Reverend McMains was the self-appointed commander of the vigilantes, though most felt like the leader was Clay Allison.

The Grant Owners petitioned the courts to allow them to demand purchase or rent monies from the settlers and on January 14, 1876, Governor Samuel Beech Axtell, a member of the Santa Fe Ring, granted the petition. The court’s decision allowed the owners to kick the settlers off the land if they didn’t pay the required rents or purchase the property from the Land Grant owners. Heaping more fuel on the fire, the decision attached Colfax to Taos County for judicial purposes, which forced the settlers to attend court in Taos 50 miles away, a trip which caused the settlers much hardship in time and money. Governor Axtell claimed the change would mean improved law and order. The citizens reacted in a fury over the bill, correctly surmising the interference of the Santa Fe Ring.

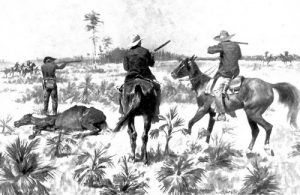

Sheriffs served eviction notices, and further retaliation began. Grant pastures were set on fire, cattle rustling increased, and officials were threatened at gunpoint. Grant gang members made nighttime raids of area homes and ranches with threats of violence to encourage their cooperation with the grant owners. It is estimated that as many as 200 people were killed in the Colfax County War.

In August 1877, Minister McMains was tried in Mora county for his participation in the Vega murder. Up until the very date of the trial, he stormed up and down the valley speaking out against the Maxwell Land Grant Company. The minister was found guilty in the 5th degree and fined $500. Minister McMains dedicated the rest of his life to keeping alive the war against the grant company, hoping to have the grant land declared open to settlers as was done with the Oklahoma Territory. Barns, homes, crops, and fences came under the torch of McMains and his vigilantes as he sought to bring the grant company to its knees.

In 1878 the law judicially attaching Colfax to Taos County was repealed, and an honest governor, Lew Wallace, replaced the corrupted tenure of Governor Axtell. In 1879, the grant was surveyed again and was declared to include 1,714,764.93 acres (2,679 square miles), though the matter was in the courts for years.

So powerful were the grant owners that in 1884 they persuaded the territorial governor to field a force of 35 “militiamen,” which were led by Jim Masterson (Bat Masterson’s brother) from Trinidad, Colorado. However, George Curry, a resident of nearby Raton, rounded up a posse of ranchers, bought up all the guns and ammo for sale. When the “militia” arrived, they marched them at gunpoint back to the Colorado line.

The guns roared for several more years until, in the spring of 1887, the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the survey and reaffirmed the decision of 1879, thus legitimizing the Maxwell Land Grant Company in its efforts to drive out the settlers. Abandoned by their government, many homesteaders bought or leased their places, some just gave up and left, and a few continued the struggle in the forlorn hope that the government might once again reverse itself. The Dutch Firm continued its exploitation of the many resources of the grant and thrived for several decades.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Rayado, New Mexico – On the Santa Fe Trail

Cimarron -Wild & Baudy Boomtown