Benedict Arnold was an American military officer who served during the American Revolution. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defecting to the British side of the conflict in 1780.

Benedict Arnold was born in Norwich, Connecticut, in 1741, the second of six children of his father, Benedict Arnold III, and Hannah Waterman King Arnold. He was the great-grandson of the Rhode Island governor of the same name. Only he and his sister Hannah survived to adulthood; his other siblings died from yellow fever in childhood.

Arnold’s father was a successful businessman, and the family lived in the upper levels of Norwich society. When he was ten, he enrolled in a private school in nearby Canterbury, Connecticut, expecting to attend Yale College eventually. However, the deaths of his siblings two years later may have contributed to a decline in the family fortunes since his father took up drinking. By the time he was 14, there was no money for private education. His father’s alcoholism and ill health kept him from training Arnold in the family mercantile business. However, his mother’s family connections secured an apprenticeship for him with her cousins Daniel and Joshua Lathrop, who operated a successful apothecary and general merchandise trade in Norwich. His apprenticeship with the Lathrops lasted seven years.

As a young man during the French and Indian War, he enlisted in the New York Militia twice and twice deserted, each time under pressure from his family to complete his apprenticeship as an apothecary under his uncles at home.

Arnold was very close to his mother, who died in 1759. His father’s alcoholism worsened after her death, and the youth took on supporting his father and younger sister. His father was arrested several times for public drunkenness, was refused communion by his church, and died in 1761. He then moved himself and his sister to New Haven, Connecticut, where he opened a small store. He became one of the most successful merchants on the coast, owning ships that sailed from the Caribbean to Canada.

In 1767, he married Margaret Mansfield, who bore him three sons.

In 1775, when the Revolutionary War began, he was a merchant operating ships in the Atlantic Ocean. He joined the growing American army outside of Boston, Massachusetts, and distinguished himself by acts that demonstrated intelligence and bravery. Arnold rode as captain of his Connecticut Militia Company to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to address what had just happened at Lexington. While there, he proposed to officials a return attack on the British. In 1775, he was granted permission to lead a force to British Fort Ticonderoga in New York and capture it. Along the way, he encountered Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys of Vermont on the same quest. After much argument, the two decided to share command; on May 3, they captured the fort with little alarm, as the commander had few guards patrolling the grounds that night. Arnold’s party then proceeded from Fort Ticonderoga to Crown Point and captured it much the same. If that wasn’t enough, the men captured Fort George (also in the Champlain Valley) by the end of June 1775. Arnold’s wife died that same month.

Although this success was considered a great one, Arnold was, in his opinion, forced from command of these new American posts. This did not hinder his ambition. In September 1775, Arnold participated in the American invasion of Canada, per orders of General George Washington. Though the attempt at adding a “Fourteenth Colony” failed with a desperate attack on Quebec, most considered Arnold to have served valiantly as a brilliant tactician and hero after being wounded in the leg during the battle. For this, he was promoted to brigadier general.

In the summer of 1776, Arnold’s skills as a strategist were once again called upon as he was placed in charge of a new American Naval Fleet in Lake Champlain. General Horatio Gates ordered him to defend the area and attack only if attacked. Upon learning of a British naval force under Guy Carleton settling in the lake’s northern end, Arnold took his fleet and stationed it towards Valcour Island in October. Several days of battle ensued. Arnold was not able to do much damage to the veteran British fleet. He only saved many of his men after grounding and burning their ships. Yet, in Gates’ eyes, he had disobeyed orders by conducting an offensive maneuver.

Now at odds with his superiors and Congress over promotions he did not receive, 1777 became Arnold’s year to prove himself. The first chance came in August when General Philip Schuyler ordered him to march west from Albany to prevent a force under British commander Barry St. Leger from over-whelming the beleaguered troops at Fort Schuyler. Arnold turned St. Leger’s superior force against him by blackmailing a loyalist man into spreading rumors amongst the Indians about his coming. St. Leger’s allies retreated, leaving him without support; he ordered his regular force’s retreat before Arnold arrived on August 21.

As Arnold returned to Albany, the Northern Army, now under the command of Gates, was bearing down for defense against John Burgoyne to the north near Stillwater, New York. After the battle at Freeman’s Farm and an argument with Gates about whether or not to attack the shaken British force, Arnold was relieved of command. On October 7, Burgoyne struck again closer to the American lines. Seeing the enemy entrenched, Arnold rode to the battlefield to lead an American attack that captured an enemy stronghold, all against Gates’ orders. This minor victory led the Americans to gain the position they needed to force a British surrender. Arnold was wounded in the same leg that he suffered an injury in Canada. Scorned by Gates but officially thanked by Washington and Congress, he was promoted to Major General and sent to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to recover, as he could not command the field.

Color guard of the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, during morning exercises. U.S. Army Photo, courtesy Britannica.com

Arnold mingled with Loyalist sympathizers in Philadelphia and married into a Loyalist family when he wedded Peggy Shippen. The couple would eventually have four sons and a daughter. She is most famous for putting him in contact with the British commanders he would later side with. As allegations of his loyalties and conduct surfaced, he requested a change of command that would put him back in New York in command of West Point, a well-fortified American stronghold along the Hudson River, which he would later try to deliver into the hands of the British.

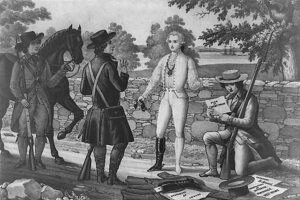

General George Washington greatly admired Arnold and gave him command of West Point in July 1780. Arnold’s scheme was to surrender the fort to the British. However, it was exposed in September 1780 when the revolution militia captured British Major John André carrying papers that revealed the plot. The British promised to pay Arnold £20,000 for its capture. Arnold escaped to the British lines, but André was hanged.

West Point’s capture would have been a significant blow to the Americans. Although Arnold could not deliver this prize, the British rewarded him with a commission as a brigadier general in the British Army, a pension, funds for lost property, and command of deserters and Tories. In the later part of the conflict, Arnold was placed in command of the American Legion. He led the British army in battle against the soldiers he had once commanded, after which his name became synonymous with treason and betrayal in the United States.

The reasons for his change of sides have been, and will be, the subject matter of much speculation, conversation, and endless books.

In the winter of 1782, he and his family moved to London, England. He was well received by King George III and the Tories but frowned upon by the Whigs and most Army officers. In 1787, he moved to Canada to run a merchant business with his sons Richard and Henry. He was highly unpopular there and returned to London permanently in 1791.

In January 1801, Benedict Arnold’s health began to decline. He had suffered from gout since 1775, and the condition attacked his unwounded leg to the point where he could not go to sea. The other leg ached constantly, and he walked only with a cane. His physicians diagnosed him as having dropsy, and a visit to the countryside only temporarily improved his condition. He died after four days of delirium on June 14, 1801, at the age of 60. He was buried at St. Mary’s Church in Battersea, England. His funeral procession boasted “seven mourning coaches and four state carriages”; the funeral was without military honors. As a result of a clerical error in the parish records, his remains were removed to an unmarked mass grave during church renovations a century later.

Benedict Arnold’s name became synonymous with “traitor” soon after his betrayal became public. Benjamin Franklin wrote, “Judas sold only one man, Arnold, three million,” and Alexander Scammell described his actions as “black as hell.” In Arnold’s hometown of Norwich, Connecticut, someone scrawled “the traitor” next to his birth record at city hall, and all of his family’s gravestones have been destroyed except his mother’s.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Scoundrels Across American History

Sources: