John’s Modern Cabins on Route 66 near Arlington, Missouri, by Dave Alexander.

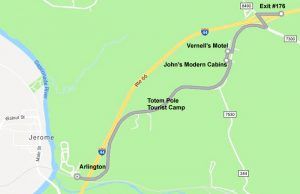

Arlington, Missouri Road Map courtesy Google Maps.

About eight miles west of Rolla, Missouri, Route 66 makes its way to Arlington Road. A dead-end pathway today, this original portion of Route 66 was once one of the most important roads in Phelps County. Today, this short three-mile trip rewards Mother Road travelers with the fading remains of several sites, including the ruins of the long-closed John’s Modern Cabins and the ghost town of Arlington.

Westbound travelers on I-44 will take Exit #176, cross south over the interstate, and turn right (west) onto Arlington Outer Road. After about a half-mile, a gravel road crosses over to a short stretch of old Route 66 pavement where Vernell’s Motel and John’s Modern Cabins once stood on the Mother Road.

Vernell’s Motel started in the 1930s when E.P. Gasser opened Gasser’s Tourist Court, which consisted of six cabins, a filling station, and a novelty shop. Later, the novelty shop also sold groceries and cold sodas.

In 1952, E.P. Gasser’s nephew Fred Gasser and his wife Vernelle bought the facility and changed its name to Vernell’s Motel. This couple expanded the property to include 12 units, an office building, a petting zoo, and a restaurant that served steaks, fried chicken, shrimp, and comfort food that enticed hungry travelers to stop. In 1957, Route 66 was widened to four lanes, forcing the restaurant and filling station demolition, and the motel was moved a few feet to the north. Afterward, the Gassers sold the property and moved to Rolla, where they owned and operated the Colonial Village on the 66 business loop at the north end of town.

Later, after the site was bypassed by I-44, new property owner Ed Goodridge and his faithful dog, Chocolate, invited travelers to visit a cozy hotel that was unencumbered by the trappings of modern-day hectic lifestyles, such as e-mail, phones, and remote controls. However, he did advertise a warm bed, a hot shower, an old TV, and the opportunity to wake up with the sun, open the screen door, and wander outside. He also encouraged visitors to wander down the road to the remnants of John’s Modern Cabins. The old tourist court and its sign still exist today, but the motel is closed.

Just about a half-mile down this short stretch of original Route 66 pavement from Vernell’s are the remains of John’s Modern Cabins. This place started in 1931 when Bill and Beatrice Bayliss established a motor court comprised of six crude log cabins and a beer/dance hall. They called it Bill and Bess’s Place, and it was a rowdy little joint that featured loud music, dancing, and lots of drinking. In 1935, a man even shot and killed his estranged wife in the dancehall and was soon sent to prison.

By the 1940s, competition was rising in the area, especially with the establishment of nearby Fort Leonard Wood in 1940, and the Bayliss’ sold the property. After changing hands three times, John and Lillian Dausch bought the property in 1951, and the name was changed to John’s Modern Cabins. John Dausch soon earned the nickname “Sunday John” for selling beer seven days a week in open defiance of the local laws of the era.

When Route 66 was widened to four lanes in 1957, the Dausches were forced to move the business a few feet north of their original location. Though they moved several of the cabins and built a few more out of concrete, they abandoned the old dancehall. They also built a larger log cabin for themselves and another building to use as a laundry room and snack bar.

By 1965, Interstate 44 was being constructed, overtaking Route 66 and bypassing former stops along the old highway. Both John’s Modern Cabins and Vernell’s Motel were bypassed at this time, and the new highway didn’t provide easy access. Business soon dried up, and making matters worse, Lillian Dausch grew ill and died. John Dausch, also in failing health, soon gave up and closed the establishment, although he continued to live there until he died in 1971. The cabins began to fall into disrepair. After 25 years, Route 66 preservationists saved the site from being demolished, but the abandoned site continues to deteriorate.

Today, the falling remains of the old lodging facility can still be seen, complete with a faded, broken neon sign atop one of the cabins that identifies the structures as “John’s Modern Cabins.” Ironically, two old outhouses continue to stand among the trees and ruins at “Modern Cabins.”

From here, another gravel road crosses back to the Arlington Outer Road. Another mile to the southwest, travelers will pass a lone remaining building on the south side of the road that was once part of the Totem Pole Tourist Camp. This attraction was built by Harry Cochran in 1933, and by the 1950s, the complex included a novelty shop, cafe, filling station, six cabins, and a shower house. In front of the building was a totem pole. However, only six buildings survived when Route 66 was realigned in 1952.

From here, the old road continues for a little more than a mile before it reaches the old town of Arlington. Located near the confluence of Little Piney Creek and the Gasconade River, this area, amid the Ozark Plateau, is a beautiful spot that has long beckoned visitors to enjoy its fishing and waterway activities.

In 1860, the Southwest Branch of the Pacific Railroad (later the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway) was planning to extend its line to the mouth of the Little Piney River at present-day Arlington. It reached Rolla in December 1860, and the roadbed to Arlington was partially complete when railroad construction was halted due to winter weather and the imminent Civil War. Troops from the 5th Missouri State Militia Cavalry often manned this area during the war.

Though the Southwest Branch operated throughout the conflict, the wear and tear of wartime traffic and the damages incurred during Price’s Raid left the railroad bankrupt. Defaulting on its mortgage bonds, the rail was sold in late 1866 to a group of eastern and Missouri capitalists headed by John C. Fremont, the famed explorer of the Rocky Mountain West and former Union military commander of Missouri. A new South West Pacific company was organized, and construction resumed.

Tracks were laid to the mouth of the Little Piney River, and in 1867, a man from Virginia named Thomas Harrison platted a townsite. After the railroad arrived, Arlington began to boom as preparations began to build a bridge over the Gasconade River. Within weeks of the town being platted, it was described as having “some thirty good buildings completed and under construction, and double or triple that number under contract.” Though the settlement was first called Little Piney, when a post office was established in 1868, it was called Arlington for Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s confiscated plantation in Virginia.

For a time, Arlington and General Fremont’s town across the Gasconade River — Jerome — were the railroad’s terminus. Many believed both would become large towns, but as the railroad pushed further west, many people and businesses followed. By 1874, Arlington had become a prominent lumber shipping point and boasted a general store, a hotel, a drug store, a sawmill, and about 150 people.

By the 1890s, the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway was making seasonal rail excursions to Arlington as a gateway to the Ozark outdoors. These beginnings of outdoor recreation soon grew into commercial endeavors as skilled Ozark guides led businessmen from St. Louis on expeditions along the Gasconade and Big Piney Rivers for fishing, hunting, and other sports activities. At that time, Arlington and other small towns in the region became known as “resort” cities.

By the 1910s, however, the sporting business changed with automobile traffic, at which time, clusters of rentable cottages became fashionable. However, the roads at that time were in terrible condition, and the Inter-Ozarks Highway Association lobbied for better roads, and Missouri State Highway 14 was created. The new road ran from St. Louis, through the outskirts of Jerome, to Springfield. In 1923, two steel bridges were built, one over the railroad bridge across the Gasconade River and the other across the Little Piney River.

In 1926, Route 66 was aligned along the gravel-surfaced road. The new Highway 66 in this area was the last portion of Missouri to be paved in 1931. During this time, Gasser’s Tourist Court and John’s Modern Cabins were erected to the east. Another main attraction was the Stony Dell Resort, established in 1932 across the Gasconade River. At that time, it was considered part of Arlington. The resort flourished in the 1930s and 1940s, especially after Fort Leanard Wood was established in 1940. Today, the remains of the old resort are considered in Jerome.

For Arlington, its heydays were numbered. Like the other places along this old alignment of Route 66, the road was rerouted and widened, and by 1946, Arlington was called home to only about 40 and no longer provided gas or other facilities. The same year, the entire town was purchased by Rowe Carney of Rolla for $10,000 with plans of turning it into a resort. However, that never happened.

In 1952, the original 1923 road bridge was bypassed when the road was widened to four lanes. Arlington’s post office was closed in 1958, and the old Route 66 bridge was demolished when Interstate 44 bypassed the town in 1966. This left Arlington at the end of a dead-end road. Aftward, Arlington became a ghost town, but for years, it continued to host an RV Park until it closed in 2008. It was the last open business in the small community.

Today, Arlington is home to only a few people but continues to display several historic buildings, including the old Arlington Hotel.

Return to I-44 on the same path to continue the Route 66 journey to Jerome at exit #172.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Missouri Route 66 Photo Gallery

Sources:

History of John’s Modern Cabins

Missouri Department of Natural Resources

Route 66 Motels

Springfield-Greene County Library District

Wikipedia