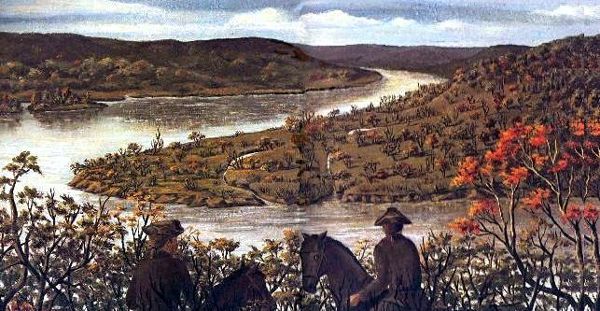

In October 1753, George Washington, just 21 years old, volunteered for a mission into the upper Ohio River Valley (now western Pennsylvania). Both the British and French sought control of the Ohio River Valley — the vast territory along the Ohio River between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River — for economic gain. Virginia governor Robert Dinwiddie sent Washington with a letter to the French who had just built two forts in the region. Dinwiddie’s letter demanded that the French leave. Captain Jacques Legardeur de Sainte-Pierre, the French commander who received the letter, refused. Washington returned to Virginia to give Governor Dinwiddie the news.

Model of Fort Duquesne, Pennsylvania

In early January 1754, prior to Washington’s return, Dinwiddie had sent a force of soldiers to build a fort at the forks of the Ohio River, where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio River (now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Before the fort was completed, French soldiers drove the British off and built Fort Duquesne on the site. In April, Washington, now a lieutenant colonel in the Colonial Virginia Army, was sent on another expedition into the Ohio River Valley, this time to build a road into the area and then help defend the British fort. Finding that the French had seized control, Washington continued to build the road and awaited further instructions.

On May 24, 1754, Washington and the Virginia troops arrived in an area called the Great Meadows and set up camp. Shortly after, Washington received a message from a Seneca leader known as the Half King informing him that a group of French soldiers was camped nearby. Washington and 40 of his men set out to find the French. Early in the morning, Washington and his American Indian allies surrounded the French and a skirmish broke out that lasted about 15 minutes before the French surrendered. The Half King spoke to the wounded French leader, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, and then killed him with his tomahawk. One French soldier escaped to carry the news back to the French Fort Duquesne. Washington, fearing a large-scale counterattack, decided to fortify his position in the Great Meadows by building a circular palisaded fort, which he named Fort Necessity.

On July 3, 1754, the French and their Indian allies approached the fort and a battle ensued. Both sides suffered losses, but the British situation was worse and that night they surrendered. After the British troops withdrew, the French burned the fort and returned to Fort Duquesne.

Fort Necessity was significant on many levels. It was the scene of the first major event in George Washington’s military career and was the only time he surrendered to an enemy. On a global level, the battle at Fort Necessity had profound consequences for the future of Britain’s American colonies — it was the beginning of the French and Indian War in North America, commonly known in Europe as the Seven Years War. The French and Indian War set the stage for the American Revolution and was a landmark event in the European struggle for empire.

While the treaty that ended the war won the British a vast amount of land in North America, the cost of war drove the country deep into debt. In order to manage and defend the new North American territory, British soldiers occupied former French forts. To help cover the cost of the soldiers stationed in North America, the British imposed a series of taxes on the colonists. These taxes sparked complaints about “taxation without representation” reviving long-standing resentments.

During the French and Indian War, the American colonists resented threats by the British commander, Lord Loudoun. Soldiers often received poor treatment from British officers. At the end of the war, new policies, including the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and new taxes angered the colonists. The “Join or Die” snake flag, designed by Benjamin Franklin in 1754 as a way of rallying the colonists to work together during the French and Indian War, gained new popularity as tensions between the colonies and the mother country increased.

Two effects of the French and Indian War became evident as hostilities escalated. First, American officers and soldiers had gained military experience and knowledge during the war. George Washington had clearly learned many important lessons and developed military leadership skills. The American colonists now knew that the British army was not invincible. Second, France was very upset about losing the French and Indian War. Their desire for revenge influenced France’s decision to ally with the Americans during the American Revolution; French aid was instrumental in the American defeat of the British.

Taxes put into place through the Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765 met with colonial boycotts of taxed items, a successful tactic that led Parliament to repeal both acts. In Boston, Massachusetts, the patriot exasperation with Britain’s taxation had been worsened by the presence of British troops occupying the city.

Discontent reached a peak on March 5, 1770, when a violent encounter between patriots and British soldiers of the 29th Regiment resulted in the deaths of five colonists and the wounding of several others. The Americans attacked the soldiers with wooden clubs, rocks, and snowballs, and threatened them with swords. During the confrontation, one soldier’s gun was knocked out of his hand by a wooden club. When the soldier picked up his gun, he fired into the crowd and encouraged his fellow soldiers to fire also. None of the Bostonians had guns. Americans called this the “Boston Massacre,” the British vaguely referred to “an incident in King Street.”

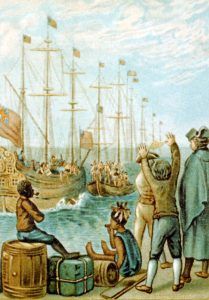

In 1773, Parliament enacted the Tea Act, which further inflamed the patriots’ sense of injustice and, in the heart of seafaring New England, threatened the profits of maritime merchants. Although the Tea Act actually reduced the price of tea while maintaining the tax, it required colonists to buy their tea only from the British East India Company, which sold directly to consumers and subsequently caused many colonial merchants to lose business. In an act of defiance against the Tea Act, the patriots of Boston orchestrated and carried out the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773.

The Boston Tea Party occurred after several meetings had been held in the city to discuss what should be done about the new tea tax. At a town meeting in Faneuil Hall on November 5, 1773, patriot leaders insisted that the commissioners of the East India Company resign. A few weeks later, when three ships loaded with British tea entered Boston Harbor, debates were held to discuss what to do about the situation. The ships were not allowed to return their cargo to England, and the customs duties had to be paid by December 16.

On that day, Bostonians gathered at Old South Meeting House for further deliberations. They made a final attempt to gain permission for the ships to leave without unloading the cargo. Captain Rotch, whose family owned two of the ships, was sent to the house of Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson, a seven-mile journey, to obtain this permission. Rotch returned to the Old South Meeting House at 6:00 pm and reported that the governor had refused the patriots’ request. After the colonists’ initial outburst at the news, Samuel Adams spoke the words that signaled patriot action: “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.” Immediately a group of patriots, recruited across class lines, went down to the harbor and dumped approximately 90,000 pounds of British tea into the water. In response, in 1774, Britain passed the Coercive (or Intolerable) Acts, closing the harbor until someone paid for the destroyed tea and forcing Massachusetts to relinquish self-government to Parliament.

Colonial hostility toward British rule reached a crucial turning point on April 19, 1775. In an attempt to quell patriot rebellion, British General Thomas Gage commanded his troops to confiscate patriot arms in Concord, Massachusetts. Relying on secrecy, Gage expected to take the arms before the patriots had a chance to resist. But couriers Paul Revere and William Dawes warned the people of Concord and nearby Lexington. When British troops under the command of Major John Pitcairn arrived in the area, they were met by a well trained and armed colonial militia led by Captain John Parker. Seventy-seven militiamen lined up on Lexington Common to face a force of 700 British soldiers. Knowing the colonials were outnumbered, Parker wanted only for his men to make a show of their resolve against the opposing troops. But someone fired a shot as the British dispersed under Pitcairn’s orders. As the militia began to flee, British fire killed eight Americans. [*editor note: No one really knows who fired the first shot of the American Revolution, known as ‘The shot heard round the world’, as there have been many contradictory accounts passed down from the event.]

After the shooting in Lexington, the British continued to march six miles to Concord where they began to search houses for arms. Some soldiers were sent across the North Bridge to Colonel James Barrett’s farm where they thought weapons were hidden. Others remained to guard the bridge. News of what was happening spread and patriot militia made their way toward Concord and the bridge. As they did, they saw smoke rising in the distance and feared that homes were being burned. Resolved to defend their homes and families, the militia continued to advance. The British fired, killing two Americans. At that point, Major John Buttrick, leader of the Concord militia, implored his men to retaliate, shouting “Fire, fellow soldiers, for God’s sake, fire!” This was the first time American militia had fired on the British army. Two British soldiers were killed in the first American volley. Outnumbered four to one, the British retreated back to town.

As the British troops prepared to set off for Boston, the Americans continued to arrive, joined by companies from other towns. At Meriam’s Corner, the colonials gathered along the road, taking cover where they could. The fighting that began there escalated into a 6-hour running skirmish. For 16 miles, along the road back towards Boston, patriot militia pursued and fired on the retreating British troops.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated March 2020.

Also See:

Paul Revere and His Midnight Ride

British Reforms and Colonial Resistance

Samuel Adams and the Boston Tea Party

Boston, Massachusetts – The Revolution Begins

Causes of the American Revolution

Source: National Park Service